The Eid Mar marvel – and other million-dollar coins

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

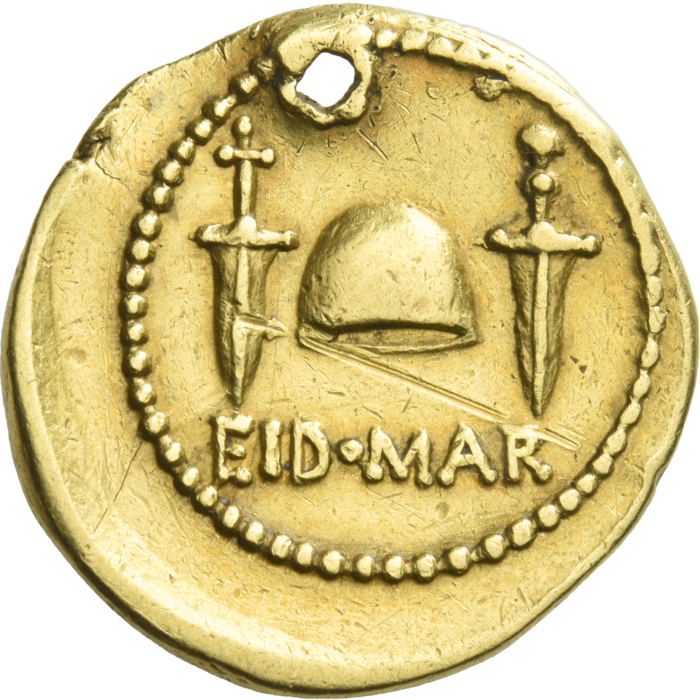

A small but potent piece of history is up for sale in Zurich this month, when Numismatica Ars Classica offers one of only three known examples of the “Eid Mar” aureus, celebrating the “liberation” of Rome after the bloody assassination of the dictator Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44BC. “This is among the most important coins of the ancient world,” explains Arturo Russo, co-director of the auction house. “To have a coin that is witness to such a significant moment in history is quite extraordinary.”

The aureus comes to the block with an estimate of SFr750,000 (about £600,000). But it should surely make much more. In 2020, another of the aurei realised £3.24mn at Roma Numismatics, an auction record for an ancient coin. The third example is going nowhere: it belongs to the Deutsche Bundesbank.

All the crucial information is on this coin, though its surface is only 2cm in diameter: the murder weapons, the date of the deed and the motive. Two daggers allude to the co-conspirators, Brutus and Cassius, while between them sits a pileus, the “cap of liberty” traditionally given to emancipated slaves. The coin’s inscription is an abbreviation of “EIDIBVS MARTIIS” – “on the Ides of March”, the month’s first new moon, appearing around the 15th. The legend around the image on the reverse, “BRVT IMP”, denoting Brutus an acclaimed military victor, suggests the coin was minted just before the battle of Philippi in Macedonia in 42BC, where the Republican plotters’ resistance was definitively crushed.

The Eid Mar coins were minted in silver (denarii) and gold (aurei). While the denarii – many more of which survive – were used to pay the armies, the aurei were almost certainly conceived as gifts for high-ranking officers. Unlike the other surviving “Eid Mar” coins, this aureus is pierced with a hole, enabling it to be worn. Some believe that the coin, which was on display at the British Museum between 2010 and 2020, was pierced shortly after being made; a curator at the BM says that the idea that it belonged to a supporter of the conspirators’ cause “seems a reasonable guess”.

There are just a handful of “Mona Lisa” coins – rare, exquisite and boasting fascinating history. The most beautiful belong to the ancient Greek world, invariably struck in Syracuse, Sicily. The tetradrachm with the head of the fountain nymph Arethusa in high relief, dolphins swimming among the tresses of her hair, is one such tour de force, signed by one of the most talented master engravers of the day, Kimon, c405-400BC. The finest specimen known made SFr2.7mn (£2.2mn) at Numismatica Ars Classica in 2014. Another spectacular work, a gold stater minted by the Greek colony of Pantikapaion featuring the expressive head of a bearded satyr, sold for $3.25mn at Baldwin’s in 2012.

Also of high value is an English gold penny, authorised in 1257 and depicting an enthroned Henry III. One found last year by a metal detectorist sold in January for a record £648,000 at Spink & Son; only seven others are known. The most valuable coins are American, though, due to the number of affluent US collectors. For them, the real “Mona Lisa” is Liberty holding a torch and an olive branch, an image conceived by Augustus Saint-Gaudens in 1907 and used for the double-eagle gold $20 coin in 1933. The only one in private hands fetched $7.59mn in 2002, and $18.9mn in 2021.

Coins such as these attract specialist – and very rich – collectors. The late Sheikh Saud bin Mohammed Al-Thani bid almost $20mn in one session for Greek coins from the celebrated Prospero Collection, the Pantikapaion stater among them. So passionate a connoisseur is Baron Lorne Thyssen-Bornemisza that he had a computerised vitrine built for his Roman Imperial coinage. A flick of a switch flips a coin over and realigns it (the reverses of hand-struck coins are never aligned with their obverses).

For Thyssen-Bornemisza, coins are a catalyst for delving into history. Even so, he says, “I bought what I found aesthetically pleasing – I think that is the only way to do it.” Indeed, adds Russo, “money is not enough. You need an eye and sensitivity.” But coin collecting can take many forms, whether in one mint, types of animals, portraits or historical events. “As my father would say,” says Russo, “there are coins for your brain and coins for your heart.”

31 May, arsclassicacoins.com

Comments