How Middleport, one of the UK’s oldest china factories, was saved

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It’s no secret that the potteries of the British Midlands have been through a terrible time. Once, the name of Stoke-on-Trent was shorthand for the most glorious fine bone china. The names of local manufacturers echoed down the years and across the oceans: Wedgwood, Spode, Royal Crown Derby, Royal Worcester – symbols of Stoke-on-Trent’s hallowed place as one of the great success stories of the industrial revolution.

In Victorian times, when demand for pottery – and in particular for porcelain (which, like bone china, is produced via a chemical process that occurs at high temperature, resulting in a product that is very strong) – was at its height and provided thousands of jobs, about 4,000 smoking kilns would have dominated the town’s skyline.

However, the 1970s and 1980s saw the start of a cataclysmic decline. It wasn’t just that Britain lost its manufacturing base, nor that factories in Asia could do most things faster and cheaper. As Dick Steele, non-executive chairman of china manufacturer Portmeirion, says: “The days of ‘fine dining’, when [couples] were given a great dinner service for their wedding and then added to it as the years went by, were disappearing fast.”

In 2009, as the world grappled with the effects of the financial crisis, even Wedgwood, probably Stoke’s most famous name, went into administration, though it was rescued by KPS Capital Partners, a US private equity firm. In the 10 years between 1998 and 2008, some 20,000 jobs were lost from the ceramics industry in the area. For many, it seemed that the decline was terminal.

The story of Middleport Pottery, however, in the heart of Stoke-on-Trent, is emblematic of a steady revival that is under way in the region.

Middleport is the oldest continuously working china factory in the UK. In recent times it has come close to being shut down at least twice. Back in 1999, when Burgess and Leigh, whose pottery is made by Middleport, went into receivership, it was within hours of being demolished when Rosemary and William Dorling, who loved blue and white china and had a business selling it, mortgaged their house to save both the company (which they then renamed Burgess, Dorling and Leigh) and the pottery. The factory was, as Rosemary Dorling said at the time, “within 11 hours of being obliterated for ever”.

By 2011, after being taken over briefly by Denby Holdings Limited, Burgess, Dorling and Leigh and Middleport pottery were once again saved by a sale and leaseback agreement with The Prince’s Regeneration Trust. The organisation undertakes the rescue and regeneration of redundant buildings of historic and architectural importance.

About £9m has been poured into restoring the Middleport factory and building, and from July 1, visitors will be able to step inside the industrial bottle kiln to see how the clay is formed, fired and decorated. The aim is to turn the factory into a creative hub for the entire area.

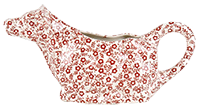

Burgess and Leigh, under the brand name Burleigh, is still making the famous Asiatic Pheasants, the Blue Calico and the Black Willow patterns that are probably its most famous products, as well as the traditional plain cream moulds and kitchenware.

Some may wonder why saving Middleport is so important, given that it is merely one of many factories in the area. The fact is, though, that Middleport is special. It is the only factory left that still uses the finest method (apart from hand-painting) of applying decoration – the 19th-century underglaze transfer printing method, which depends upon hand-engraving the patterns on to rollers.

“This is not just a collection of moulds, it’s a slice through British ceramic history. The aim is that it will act as a catalyst for the regeneration of the whole area,” says Steven Moore, a British antiques expert, who is also an ambassador for Middleport Pottery. “The amazing thing about it is that while it looks exactly as it did in the 19th century, it is in fact a perfect working pottery.”

Ros Kerslake, chief executive of The Prince’s Regeneration Trust, adds that Middleport Pottery is “a living and breathing part of British industrial history”. The project conserves much of the building’s industrial heritage, including the last remaining brick-built bottle kiln, so named because it is shaped like a bottle.

Today, there are an estimated 8,000 people in the industry in Stoke. Most of the jobs are at Steelite International, Dudson and Churchill, all of which supply the catering and hospitality industries.

Some of the consumer tableware and giftware manufacturers, such as Portmeirion and Emma Bridgewater, are seeing growth in sales. Dick Steele says that today Portmeirion produces “150,000 pieces of pottery a week, twice as many as we were producing five years ago”. While its best-selling Botanic Garden range earns £25m annually, Sophie Conran’s collection, launched in 2006, has been a huge success and accounts for some £7m each year. That, together with the publicity generated by the Middleport rescue, has helped stir local interest.

Key to the revival of the industry has been the realisation that design and innovation were needed to create fresh interest.

“We have to be what we’ve always been, but we must also add in something new to keep desire alive,” says Steele. Many of the other companies have also seen the need to innovate and refresh their ranges.

Peter Ting’s Hachi range for Royal Crown Derby, for example, is contemporary yet beautifully shows off the traditional skills and crafts that the factory is known for. At Wedgwood, designers such as Jasper Conran and Vera Wang have set the tills ringing once again. At Royal Doulton, graffiti artists including Pure Evil (real name Charles Uzzell Edwards) have put their brand of streetwise imagery on to a new sell-out range called “Street Art”.

Kevin Oakes, chief executive of Steelite, which bought Royal Crown Derby in late 2012, is optimistic about its future: “We want to put it back on its pedestal, producing the very fine bone china that it is famous for.” Royal Crown Derby has started recruiting again, and that is not the only good news for Stoke: more encouraging still is the fact that a lot of the manufacturing that had moved to Asia is being brought back to the area.

This is due largely to a combination of the rising price of labour in Asia and the fact that some companies are beginning to count the cost of less reliable quality.

Portmeirion, for example, which bought Spode and Royal Worcester out of administration in 2009, has moved some of its production, most particularly Spode’s distinguished Blue Italian range, back to Stoke.

Meanwhile, the current interest in craft has meant that a number of small craft-based potteries are moving into the area, of which probably the most famous now is Emma Bridgewater, which continues to flourish, employing about 250 people with an annual turnover of about £14m.

All the signs are that the “Made in Stoke-on-Trent” badge is beginning to matter once again.

Lucia van der Post is a contributing editor to the FT’s How To Spend It magazine

——————————————-

Jacqui Heames – specialist decorator

Jacqui Heames has been at Middleport for 11 years, and even she has difficulty remembering where everyone operates in the maze of workshops, writes John Murray Brown.

She is part of a small team of specialist decorators, hand-transferring patterns on to pottery. A technique that was once used in all the potteries in Stoke, it is now found only in Middleport. The process is similar to lithography. She first cuts out the pattern from a sheet of tissue using a sharp blade. The pieces are then attached to the unglazed pottery and worked into position with a damp flannel. Because the pattern is oil-based, it sticks; the paper is brushed away using wet soap.

It requires nimble fingers and a keen eye to ensure the pattern is positioned correctly. It is also hot work, with the transferring shop directly above the kilns. “The biscuit ware (the unglazed pottery) is very porous so it sucks the print into the ware,” says Heames, as she puts the final fiddly bit of pattern on a small rice bowl.

…

Keith Flynn – kiln placer

Keith Flynn’s first job as a 16-year-old was as a saggarmaker’s bottom knocker, a job title so exotic it once featured in a British television panel show that discussed unusual occupations.

The saggar was the ceramic container used to protect the ware when it was put in the kiln for firing. And the bottom knocker’s job – which was usually done by teenagers – was to beat the clay into the bottom of the container using a wooden mallet.

“In the old ovens, you would sit for three or four days and wait, crossing your fingers and hoping the ware was all right. It’s a cleaner job now, but it’s still hard work. The basics haven’t changed much.”

Flynn joined Middleport in 2007 after being made redundant at Wedgwood, the most famous Stoke brand. The pottery had just 18 staff. Today, if the shop and offices are included, Middleport supports about 100 jobs. “If you go around the factory, there are lot more young ones, and hopefully more coming in the future when they see we’re a thriving pottery again,” says Flynn.

…

Chris Rhodes – glazer

“I’ve been dipping now for the best part of 40 years”, says Chris Rhodes. The 57-year-old wears the traditional white work smock that makes him look a little like a surgeon.

His job is to apply the glaze to the plates and cups, ready for final firing in the kiln.

“There is no other way of doing it,” he says as he submerges another oval platter into the vat of pinkish liquid, shaking off the excess glaze before laying it on the conveyor to the drier.

He has plastic finger mittens on his right hand to help grip the slippery ware. “We also use the hook and leather,” he says, pointing to his female workmate, who has a hook extension on her thumb held in place by a small leather sock. With this, she vigorously spins each newly glazed plate to get an even finish.

“This is an old technique, which we’ve always used in this industry since the beginning of time,” says Rhodes.

Like others working at Middleport, he is upbeat about the company’s prospects. “Well it should see me out,” he says.

John Murray Brown is the FT’s Midlands correspondent

Comments