Executive course opens doors for Arab Israelis

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

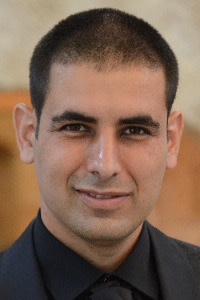

Alaa Hbaish did not wait long to act on the inspiration he received on a pioneering programme to boost the low number of Israeli Arabs employed in managerial roles in the country.

Scarcely halfway through his intensive training in business and leadership, which included a master’s degree in Israel and an executive education course in Cambridge, Hbaish decided to challenge the lack of Arabs among faculty and staff at Tel Aviv’s Coller School of Management.

“I felt discriminated against because of my name,” he says. “I know Arab students would prefer to stay silent, because their goal is to finish the MBA and go home. But, because of the programme, I decided the MBA wasn’t my main goal. It was to change this status. I thought, ‘If I’m experiencing this and don’t do anything, my son will, too, at some point.’”

Hbaish lobbied Dan Amiram, the then vice-dean who now runs the school, to increase diversity. Since that time, it has hired Arab staff including three adjunct faculty, five teaching assistants and four research assistants. “Our goal is to continue to lead the expansion of the representation of Arab society in the academic and administrative staff, as well as being attentive to the students and improving learning and the student experience,” says Amiram.

Hbaish’s experience reflected a broader structural issue that the backers of his programme are trying to tackle. Elli Booch, director of philanthropy at the Edmond de Rothschild Foundation in Israel, cites a study by Israeli NGO Co-Impact showing that, while Arabs comprise 21 per cent of the population, they make up only 5 per cent of employees in larger businesses and 0.3 per cent of managers.

“We started a decade ago by saying, ‘Let’s bring more of the Arab community into higher education to boost access,’” says Booch. “That’s now very close to reaching fair representation, but the issue has become the link to employment. Our main goal was to create role models. When you are at work and there’s no one from the Arab community, there’s no one to inspire you.”

The Edmond de Rothschild Foundation funded the charity Kav Mashve to launch the Al-Mada executive empowerment programme in which Hbaish participated from 2020, and which is now training its second group of a dozen participants. The aim is for them to become more confident, be willing to take risks to gain promotion, and become role models for others.

With the support of their employers, the participants continue to work while studying part-time for an MBA in Tel Aviv, attending training courses with the Institute for Quality Leadership and taking an executive education course at Cambridge University.

Sami Asaad, chief executive of Kav Mashve, says that improving resilience and self-awareness is one of the key benefits. “Israelis are more individualistic. We Arabs grow up with another background, with more collective and less personal skills. We try to close that gap.”

Jennifer Corbett, who helped oversee the one-week executive education course at Cambridge University’s Judge Business School, says the programme — soon to be repeated for the next group — was unusual, not only because the participants were fairly junior but also because they came from a range of employers rather than a single organisation.

“We had to work on a much more individualised level,” she says. “It would have been easy to latch onto the fact that they were Arabs, but we wanted to bring out the other ways that they were different, by sectors, backgrounds and from across Israel — from very remote small villages to Tel Aviv.” She adds that a key benefit participants signalled was greater insight into soft skills, including networking.

Hbaish, a Druze from rural northern Israel who works for ICTS Europe, the French-based security company, says: “My first goal was to get some tools to enable me to do a better job and qualify me for a better career. Second, it was to understand my potential, my capabilities, and how can I achieve them.”

He says the programme helped him go beyond IQ and EQ (emotional intelligence). “I learnt about CQ — which refers to cultural flexibility. I understood the difficulties people have with my culture, how I have to adjust, and how both sides have to be flexible.”

While the programme is still in its infancy, Asaad says nearly all of the first group have already been promoted into more senior roles: “It’s a model for other young people from the Arab community to show that, when we are proactive, we can go high. It’s also changing the mindset of employers, who become more open.”

Much work lies ahead. The programme does not include Palestinians. And it remains modest in size, although its backers hope that a strong track record will attract other funders, including the government.

In the first cohort, most participants did not work for Israeli businesses but international companies such as Microsoft, Intel, P&G and KPMG, which have subsidiaries in Israel and existing policies on diversity. However, Asaad says the second group already includes more from locally headquartered companies.

Like most of his peers, Hbaish has already been promoted, but his ambitions don’t stop there. “I want to be in charge of bigger projects, bigger budgets, bigger subsidiaries. In 20 years, maybe I’ll have my own company quoted on Nasdaq,” he says. “But I will always remember where I came from. And the community that supported me. As the Arabic saying goes, ‘Heaven without people doesn’t mean anything.’”

Comments