Philanthropists play a crucial role in developing vaccines

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

With long time horizons, complex science and high failure rates, vaccine development is not for the faint-hearted philanthropist. But in a world gripped by coronavirus, many donors have put aside such concerns and are writing large cheques in the hope of contributing to the end of the pandemic.

Alibaba founder Jack Ma has promised more than $14m for coronavirus research, while the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has pledged up to $100m to the global response to Covid-19, including funding to accelerate the development of vaccines.

Even the Gates Foundation’s move pales in comparison with the funds now being committed by governments and pharmaceutical companies. In the US alone, the National Institutes of Health, the federal research centres, have secured $1.8bn in additional government funding for Covid-19 work, including vaccine investigations.

Meanwhile the American drugs group Johnson & Johnson is putting $1bn into developing a specific coronavirus vaccine, in a project jointly funded by the US government.

But charitable dollars can still play a crucial role. Philanthropy advisors say donors are free from the burdens of politics that often hamper policymakers and from the profits drive that influences companies (even if, as with J&J’s Covid-19 vaccine, executives claim a particular move is profit-free).

This can allow philanthropists to back very long term research and bring together disparate groups of partners, including universities, research laboratories and other donors.

“We can fund longer timelines than government or industry,” says Heather Youngs, programme officer for scientific research at Open Philanthropy, a research and grant-making organisation. “They have constraints because of the stakeholder groups they have to answer to, whether voters or shareholders. So philanthropy can fill in the gaps.”

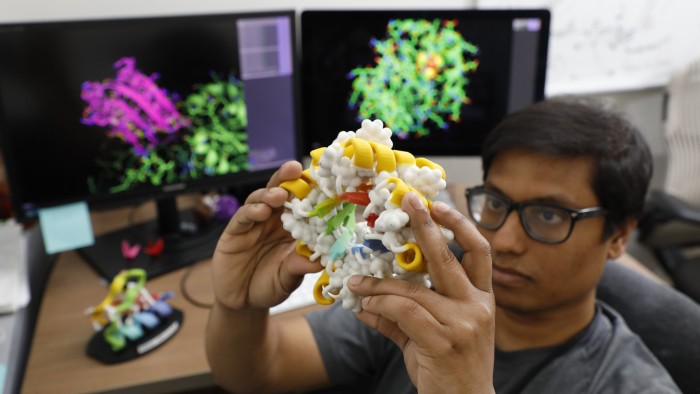

An example is Open Philanthropy, where the main funders are Cari Tuna and her husband and Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz. The foundation makes grants to vaccine research centres globally, such as a 2017 award of more than $11m to support research at the University of Washington’s Institute for Protein Design for the development a universal influenza vaccine.

Philanthropy is particularly important in vaccine development because drug companies find it hard to achieve a financial return on the large, long-term investments needed. “You get these glaring market failures, many of them in the vaccine space,” says Mark Suzman, chief executive of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which since inception has committed more than $18bn to the discovery, development and delivery of vaccines.

Suzman cites malaria, which despite being responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths a year, still has no effective vaccine.

“We don’t have malaria problems in rich countries because we have effective prophylaxis: if you visit a malarial zone, you can take pills and you won’t get the disease,” he says. “So there isn’t an incentive for the private sector to put in the billions of dollars that are needed to underwrite a new vaccine.”

And while large pharmaceutical groups were successful in developing an Ebola vaccine, the market — limited largely to a few African countries — was not large enough for them to recover their costs. “In the end they are businesses, and some of them got quite burnt by that,” says Suzman.

When companies do invest, it tends to be in the later stages of vaccine development, says Melissa Stevens, executive director of the Milken Institute Center for Strategic Philanthropy, which advises families, foundations and individual philanthropists.

Charitable dollars can play a critical role in closing the gap between the original research project and delivering a vaccine to the public, perhaps 10-15 years later.

Donors fund the earlier, riskier stages in the journey of vaccines from academia, government labs and entrepreneurial biotech firms to pre-clinical trials and ensuring they meet the regulatory standards needed to enter clinical trials. “That’s where philanthropy can have an outsized impact,” says Stevens.

British philanthropist Richard Ross agrees. He chairs Rosetrees Trust, a fund specialising in medical research established by his late entrepreneur parents, which has distributed nearly £50m since its foundation in 1987.

“A lot of [early research] is basic science, which can be 30 years away from practical application in medicine,” he says. “People come and say I can’t get grant money because I have no data. We can make a difference with one year’s money or three years’ money. That’s an entrepreneurial approach.”

Rosetrees, which has set aside money for Covid-19 research, is considering about 10 projects, including one involving a drug used for brain tumours and another an existing tuberculosis vaccine.

Philanthropists can also fund vaccine-linked education. “You see a growing anti-vaccination movement based in ignorance,” says Amir Pasic, dean of Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. “You can’t overestimate the importance of education, and I think we’ll see more of that.”

While philanthropists financed vaccine research long before Covid-19 came along, the pandemic has sparked a wave of interest among potential new donors.

Eric Kessler, founder, principal and senior managing director at Arabella Advisors, a US-based philanthropic consultancy, says: “Donors who have historically focused on global health are tripling down right now, and many donors who’ve never focused on global health are getting into the fray for the first time. It’s hard to know how much is going specifically into vaccine research, but we can say it’s significant.”

Kasey Oliver, a director in the consulting practice at philanthropic advisory company Geneva Global, says that as well as reacting to an event such as the Covid-19 pandemic, donors can be motivated by anything from wanting to help eradicate a disease that has killed a family member to wishing to bet on something that could bring long-term change.

However, participating in vaccine research as a philanthropist is not easy. First, it involves complex and emerging science and so means relying on experts. “You need to be willing and able to be flexible and a little hands-off,” says Stevens. “And not everyone goes into their philanthropy with that type of mindset.”

And because it requires the involvement of the private sector, particularly in manufacturing and distribution, donors may face obstacles in ensuring that any successful vaccine can be sold cheaply enough to benefit poor communities.

To address this, in 2003 the Gates Foundation developed its Global Access model for grant contracts. This stipulates that companies or universities that receive its funding must make the resulting treatments widely available at affordable prices. They are also required to share data.

Another challenge for individual philanthropists without the resources of billionaire donors is the sheer amount of money required for vaccine development.

This was among the reasons behind a new collaborative fund, which was launched in January to accelerate the development of vaccines against emerging diseases.

With an initial investment of $460m from the German, Japanese and Norwegian governments, the Gates Foundation and the UK’s Wellcome Trust, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations acts as a hub to which any philanthropist can contribute. The group has issued an urgent call for $2bn to develop a Covid-19 vaccine.

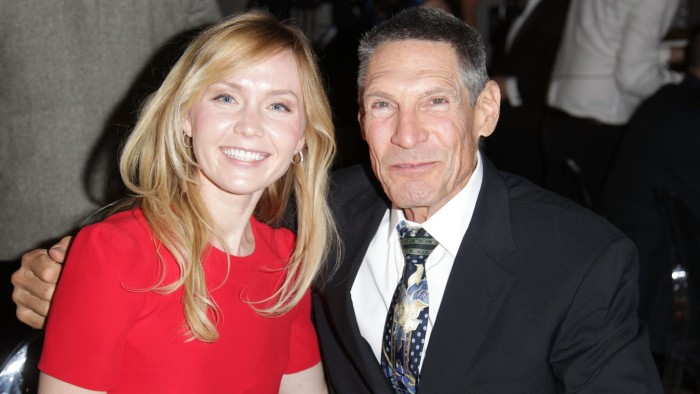

Another way for a philanthropist with less money than Gates to help is to create a prize to stimulate academic competition. American philanthropists Gary and Alya Michelson have done just that through the Michelson Prizes. Their annual awards go to young scientists — each winner receiving $150,000 — who are working in new ways on human immunology, vaccine discovery, and immunotherapy research in major global diseases.

At least with prizes, the donors’ names can be recognised. Otherwise, unlike with gifts to an opera house or university building, or even the endowment of an academic post or a scholarship, it is hard to attach a donor’s name to long-term medical research. “Does this appeal to people who want their name on the wall? No,” says Ross.

Moreover, with vaccine projects, as with most long term medical research, there is the likelihood of failure. Few donors want to fund a loser. But developing vaccines, from the pre-clinical phase to production, typically takes more than a decade and has just a 6 per cent probability of making it to market, according to a 2013 study led by researchers at Erasmus University in the Netherlands.

“The trouble with vaccines is they’re expensive,” says Peter Hotez, co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital. “You need substantial funding and the timelines are pretty long — and often donors, especially the more entrepreneurial donors, want a more immediate return. That’s the toughest part of this.”

But Maria Elena Bottazzi, Hotez’s co-director, argues that even when it results in failure, funding vaccine research is extremely valuable. “It’s transformative, because you are at the same time building the next generation of innovators and scientists,” she says.

And, as the coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated, success can have a social and economic impact that is global. “Where would we be right now if we had a vaccine for Covid-19?” says Oliver. “Vaccines are game changers. They reshape the world — imagine if that was part of your philanthropic legacy.”

Comments