Es Devlin’s work of ark

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Networks, systems, patterns, connections – these are the constant concerns of Es Devlin, whether she’s designing a stage set for Hamlet with Benedict Cumberbatch, a stadium spectacular for Kanye West, Adele, U2 or Beyoncé, or the closing ceremony of the London 2012 Olympics. The writer Andrew O’Hagan has described her as “the Jung of set design”; her regular theatre collaborator, director Lyndsey Turner, has it thus: “She designs the ideas, the thought structures, the systems in which characters operate.”

It’s not a surprise, therefore, that when she lets me into her Victorian home in Dulwich, which also doubles as her design studio, the first thing she does is take me on a tour through the rooms. Here, I find members of her team sitting in front of laptops or 3D-printing cute little chairs for a model of the stage set for a new production of The Crucible at the National Theatre. A vast open-plan living room/dining room/work room/kitchen gapes onto an oasis of a garden – at one point during our interview her young son ambles through and out to a trampoline. Devlin loves the fact that her two children (she is married to costume designer Jack Galloway) are growing up seeing no division between their mother’s work and home life. “The membrane between work and life is very porous,” she says. “I really like the fact that they know what I do.”

Exactly how porous is made clear by Devlin’s current project, sheet after sheet of beautiful, detailed pencil drawings of mammals, birds, fish, insects, spiders and plants that occupy the whole surface of her refectory-like dining tables, and spill over onto the living room walls. In all there are 243 drawings representing the species that the London Wildlife Trust thinks “are most at risk of extinction. So what I’ve been doing for the past year is drawing these 243 species – painstaking, careful, late-night drawing for many months, because they take ages. And because my kids have seen me doing them, they’ve now started texting me pictures of moths. I mean, that’s a result.”

In person, Devlin is relaxed, dressed casually in a black cotton top, soft white joggers, her long black hair pulled up in a bun fixed with a pencil, and two gobstopper-sized rings on the middle fingers of her right hand. Within, she’s bursting with energy, weaving off on conversational tangents, with a hunger for knowledge. While much of Devlin’s career has been spent finding ways to interpret other artists’ texts, whether by playwrights such as Shakespeare and Pinter or pop and rock stars, she has in recent years begun to create a significant body of self-authored work, including films, immersive installations and interactive sculptures. A concern for the planet and the threat of extinction runs through many of them, whether in her film I Saw the World End (2020) about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, her installation called Memory Palace (2019), which told the story of world history through a mini 3D map (its payoff: “Remember the low-lying deltas where rising seas are being first felt”), or the 197 trees she installed at COP26 to witness the decisions 197 countries would make about our future.

This latest project is a collaboration with Cartier about London’s endangered species. It is called Come Home Again (21 September to 1 October), taking its title from a line in the 1991 book World as Lover, World as Self by the 93-year-old climate activist Joanna Macy. Macy’s “Great Turning” initiative has focused on making the shift from a society driven by industrial growth to a more sustainable civilisation. “Now it can dawn on us: we are the world knowing itself. As we relinquish our isolation, we come home again… We come home to our mutual belonging,” she wrote. Macy’s call for us to reach a deeper understanding of our interconnectedness with nature resonated with Devlin, whose 2021 installation The Forest of Us, still showing in Miami, is all about the way our internal body structures are mirrored in the natural world.

“I was interested in the correlation between the geometry of what’s inside us and the geometry of what’s outside us,” says Devlin. “Look at your lungs, look at a tree, understand the connection. I wanted people to have this feeling that the edges of yourself need to be considered in a much more expansive way, to take in the whole network that you’re part of. I thought, ‘If there’s one thing that I could do that might be helpful, one little acupuncture point that I might help to press in a small way, it might just be that consideration of, “Where does yourself end?”’ Then I thought, ‘Where do I start? London: let’s think about London.’ It’s estimated that nearly 70 per cent of us are going to be living in cities by 2060. Nature can’t be outside the city. This whole process that I’m talking about, extension of the edges, has to be what city dwellers do. So I went to the London Wildlife Trust and looked up all its data. And I found the list of 243 species at risk and thought, ‘I can pay attention in detail to 243. I can draw them off.’ So that’s what Come Home Again is.”

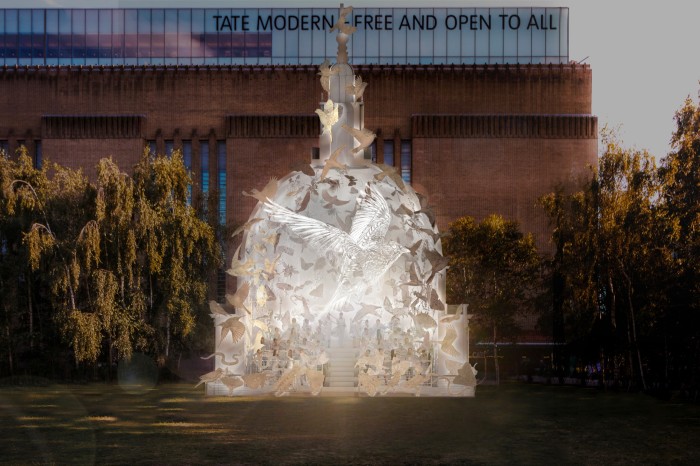

In fact, the drawings are just the beginning, as each depiction is being blown up in size and printed onto a sustainably sourced 2m board, which will hang, illuminated and projected on, around a sliced-open, scaled-down model of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in front of Tate Modern. Inside the dome will be choir stalls where, during the day, visitors can sit listening to a soundscape of Devlin saying, and a choir singing, each of the 243 species’ names. In place of hymn books there will be QR codes giving access to information about all of the species mentioned. Every evening a London choir will sing evensong live from within the dome.

Devlin hopes the simple act of giving voice to the endangered species will be transformative. There are well-known names such as the swift and the house martin, but most of us are less likely to be intimately acquainted with the olive earthtongue, the depressed river mussel or the German hairy snail. “There’s a book, Rewild Yourself, by Simon Barnes, and he says, ‘Learn their names. The name changes everything. You’ll no longer be listening to a vague thing or bird song. You’ll be listening to music you know and love.’ So it seems to me that the most useful thing I can do is invite people to learn the names of the animals closest to them. I want them to think, ‘Actually, this network of animals in my city is completely continuous with the network that I’m part of. Any harm I do to it or any manner in which I ignore it is actually doing harm to myself.’ That’s the shift we all need to, rather quickly, make in our brains.”

Piled up around us is a library of books that Devlin has drawn on for her research. She quotes Rebecca Solnit, Richard Powers’ Pulitzer-prize winning The Overstory, and regales me with the tale behind Robert Hooke creating his Micrographia. It’s a leap from all this to the massive cubes showing projections of sharks and tigers Devlin created for Kanye West and Jay-Z’s Watch the Throne tour in 2011; but surfing between “high” and pop culture is one of Devlin’s superpowers. How different does she find working on a solo project like Come Home Again and staging a mega-concert? “D’you know what? Those great artists that I’ve been ridiculously fortunate to have collaborated closely with, many over a long period now… they are lightning rods, I think, they’re conductors. Their music resonates, a bit like the choirs that will perform in Come Home Again; it finds a vibration in all of us and that’s why everyone wants to tune into it.”

The opera director Keith Warner has described Devlin as “the most driven person I’ve ever met in my life.” So it’s no surprise that Come Home Again is just one of the many projects she’s been pinballing between: in February she designed the half-time show for the Superbowl; she’s just created a monolithic ring for Saint Laurent’s SS23 menswear show in the Moroccan desert; then there’s The Crucible in September and a collaboration with Sam Mendes and Jack Thorne, also for the National, on a new play The Motive and the Cue; she’s also contributing to COP27 in Egypt in November. But one thing she won’t be working on is Adele’s rescheduled performances in Vegas. Devlin was the designer for the original shows that were cancelled back in January and there were rumours that it may in part have been due to disagreements over the set. Was there any truth in them? “The reason I haven’t said anything is there’s nothing to say,” she says. “If there was more of a story, I would honestly be thrilled to tell you it, but there’s nothing. She was a delight to work with throughout. She’s a friend.”

As to the future, she’s aware that as a designer creating monumental global installations and yet talking about the importance of averting climate change, she leaves herself open to accusations of hypocrisy. She nods and quotes a line from a U2 song, “I must be an acrobat, to talk like this and act like that.” But, “On the positive side, it’s my direct experience that every Zoom I’m in on, every room I walk into, I feel far more greatly emboldened to open my mouth and say, ‘How are we auditing the carbon emissions on this project?’ That wasn’t a question that would have been routinely brought up, even two years ago. Now you can open your mouth.”

She’s hoping that Come Home Again might have a life beyond its September tenure outside Tate Modern, but if it doesn’t, nothing will go into landfill: “All of its particles will go back into circulation.” More importantly, Londoners and visitors from beyond will know that little bit more about those 243 species, from the swift that flies the equivalent of seven times to the moon and back in its lifetime, to the 450 million-year-old sea lamprey (“When I was Googling it to find a picture of it, you find it, more often than not, pictured on toast, which is really unfortunate”) and the streaked bombardier beetle that’s clinging on to its existence in the UK by a thread in Tower Hamlets.

Comments