A variety of students is the spice of classroom life

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A tailored blue suit. Designer shoes. An air of assured self confidence. Such is the perceived stereotype of a typical MBA graduate.

But a growing recognition that the world’s intractable problems need business solutions means MBA directors are searching for students with a more diverse background to fill their classrooms. Increasingly forgoing the narrow cadre of applicants destined for banks and consultancies — industries that just a decade ago employed two-thirds of top MBA graduates — directors want students with different work experience, nationalities and aspirations. As a result, tomorrow’s MBA graduates could look very different from today’s.

At MIT, Maura Herson, director of MBA programmes, says that the Sloan school has had some success in this, with one-third of MBA candidates submitting scores from the GRE test, the generalist postgraduate entry test, rather than the GMAT, which is tailored to business students. “We might be attracting people who did not originally think to do an MBA,” she says. However, just how to achieve this rebalancing trick is increasingly taxing deans.

The Darden school at the University of Virginia is targeting applicants who have worked for Teach for All, a global network of social enterprises that recruit top university graduates to teach in their country’s high-need schools. Meanwhile, the Saïd school at the University of Oxford has introduced a 1+1 scheme in which those with masters degrees from other Oxford departments, such as computer science or geography, can follow this with a one-year MBA.

As business graduates eschew high-paying jobs in banks and consultancies for not-for-profits, non-traditional industries and start-ups, the high price of MBA degrees is thrown into sharp relief. The top schools, particularly those in the US with large endowments, are tackling the problem by sinking funds into scholarships and fee waivers.

There are even rumours of schools paying stipends to attract the very best. All are fighting over a limited pool of rock star students. Only 16,000 of those MBA applicants who sit the GMAT test each year have a score higher than 700, the score favoured by top schools, but the top 10 schools in the 2015 FT MBA ranking snap up 6,000 elite applicants on their own.

As a result, the MBA market is bifurcating, with big brand business schools spiralling away and fighting over a small number of high-class students and lesser schools floundering and thinking deeply about how to fill classes.

See our directory of full-time MBA scholarships offered by business schools around the world

Those schools fighting to remain in the top echelons are trying to be innovative. Last month the Simon school at the University of Rochester reduced the sticker price on its two-year MBA from $106,440 to $92,000 for the 2016 intake, for example, allocating scholarship money away from individual high-flyers. The aim is to increase student numbers from 100 to 120 or more using this egalitarian approach.

Andrew Ainslie, Simon’s dean, makes a robust defence of the decision: “I don’t like to think of it as a price cut; I like to think of it as price transparency.”

IE Business School’s strategy for attracting the best includes active involvement on social media. In fact, LinkedIn recently awarded IE the accolade of being one of the top three content marketers in Spain. “Recruiters for companies search through social networks,” says dean Santiago Iniguez. “We do something similar.”

At Sloan, Ms Herson says there has been a concerted effort to persuade those on undergraduate programmes to consider business rather than law and medicine. She believes other schools should do the same. “As an industry this is something we can do co-operatively.”

Meanwhile free online programmes are now often used to showcase business school wares. At Michigan Ross, finance professor Gautam Kaul says it is a way of giving course tasters. “These days there are lots of people in my class who have seen me before. But they have also seen professors from Wharton and Yale,” he says, yet adds: “Globally, we haven’t even touched the surface.”

While European business schools have been attracting overseas students for decades, only in the past few years has this approach been seen as an answer to the problems of US business schools, where the number of eligible US students remains static or in decline.

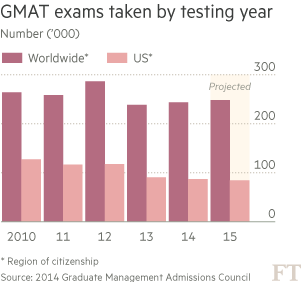

Figures from GMAC show the number of US citizens taking the GMAT test fell 31 per cent between 2010 and 2014, and that number looks set to fall again by 3 per cent in 2015, according to Alex Chisholm, senior director for research services at GMAC, even though preliminary figures show a 2 per cent increase in global GMAT testing, with demand growing the fastest in Asia.

To compound the problem, US students are frequently looking to study overseas. They are the largest single nationality group on the MBA at London Business School, while nearly 20 per cent of students on the MBA at Oxford are from the US. The five largest nationality groups at Insead are from the US, India, France, China and Brazil.

Attracting students internationally is not all plain sailing, says Ilian Mihov, dean of Insead. “Our latest MBA cohort of 490 students come from 77 different countries. This makes sales and marketing somewhat of a challenge,” he says. Insead, as a result, relies on a network of alumni to help source students.

Away from the elite group of 20 or 25 business schools, low-cost programmes with online delivery are snapping at the heels of many of the more traditional business schools, now forced to either retreat to a local market or compete head-on with low-cost technology and cheaper fees. Such has happened at the University of Illinois (see sidebar below).

What is more, all schools are seeing the market fragment as students opt instead for one-year masters programmes or even professional qualifications, such as the CFA.

To top it all, elite US business schools may face an even bigger issue. There has traditionally been an inverse relationship between the strength of the economy and that of business school applications. As the US economy booms, many now fear the corporate world will prove more attractive to young high-flyers than the world of academia.

Other features in this series:

Industry savvy teaching keeps courses in the game

Poor finances threaten business schools

Short tenures signal leadership void

Comments