Overdue reality check for Fed and markets has barely begun

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is chief investment officer at Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

The US Federal Reserve and financial markets are experiencing a long overdue reality check on inflation and interest rates. But markets have barely begun to take into account how far the world has changed.

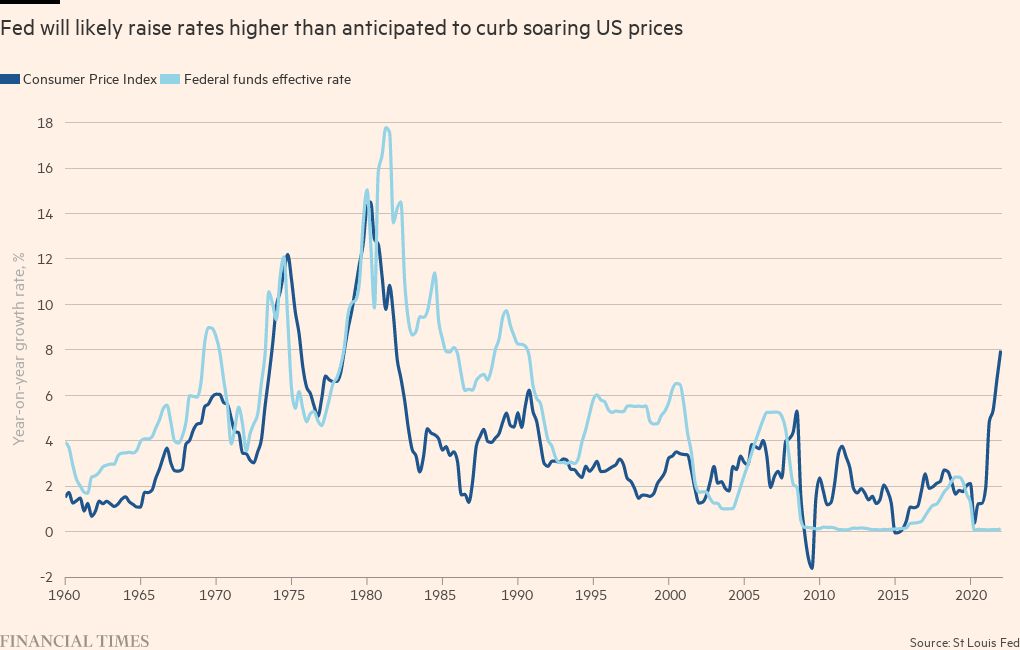

I believe they are still experiencing a severe case of cognitive dissonance. Inflation has surged to levels not seen since the infamous 1970s and remains stubbornly high. The Fed has started tightening, with policy rates already moving up and the central bank set to shrink its balance sheet after ending its market-boosting asset-buying programme.

But even after the evidence of inflation rises in recent weeks, most investors still expect interest rates will not rise very much and will not remain elevated for very long. I think this may be very misguided.

Markets anticipate that US economic growth will slow as we head into 2023 — and here I would agree. High inflation has taken a toll on purchasing power and will hurt household consumption, even though real income still exceeds pre-pandemic levels. Supply chain disruptions continue to hamper production, and the combination of somewhat tighter monetary policy with less generous fiscal stimulus will hold back activity.

Financial markets have been conditioned to believe that the Fed will react to this slowdown in growth in the same way it always has in the post-financial crisis period: by loosening monetary policy quickly and decisively. This is where I expect things will play out differently.

This time when growth slows, inflation will in all likelihood still be too high for the Fed to stop tightening. Month-on-month headline consumer price inflation has averaged 0.6 per cent since the start of last year. Even if that monthly pace halves, inflation will end 2022 close to 6 per cent year over year, and will be running at an average of 4.5 per cent in the first quarter of 2023.

If financial markets are nonetheless expecting the Fed to quickly ease policy again, it’s at least in part because their cognitive dissonance has been abetted by a significant degree of wishful thinking that seems to inform the central bank’s own outlook.

The Fed seems to be hoping that inflation will fall back to its 2 per cent target despite policy interest rates remaining negative after taking into account inflation. Bringing inflation down in such circumstances is a feat that the Fed has never managed before.

How likely is it that the Fed will pull that off now without a more decisive policy tightening? The Fed seems to be betting that inflation expectations will remain anchored until all exogenous shocks have been worked out of the system. But consumers’ long-term inflation expectations are already running at about 4 per cent and wages are rising at a 5.5 per cent pace (average hourly earnings of all employees).

Every month that goes by, inflation expectations become entrenched at a higher level as workers, consumers and businesses learn to anticipate and get ahead of persistent increases in their cost base. When activity slows, it could take some pressure off this very tight labour market. But with labour force participation persistently below pre-pandemic levels, the cooling impact on wage growth might be limited. We have a wage-price spiral developing that will probably make inflation more self-sustaining than the Fed assumes.

We operate in a very different environment than we did a decade ago. Inflation has asserted itself as a major social and political issue for the first time in more than 40 years. The year-on-year rate may abate in coming months because it is measured against the higher base of inflation as 2021 progressed. But the effect will be slow and we will always be one supply shock away from inflation bumping back up. During the past 12 years, the Fed could always afford to give priority to supporting economic growth and asset prices because inflation remained blissfully dormant. This is no longer the case.

I therefore expect that even as growth slows, the Fed will keep hiking rates during the first half of next year, in order to bring inflation back under control. And that once markets realise the Fed cannot afford to reverse course, long-term yields will also move higher still.

We still need to acknowledge fully that inflation has become self-sustaining and bringing it back under control will be harder and more painful than the central bank hopes and financial markets are pricing in. This time, the Fed’s tightening cycle will be longer, and policy rates and bond yields will have to go higher than markets currently expect. The corresponding risk to asset prices and economic growth is greater than many like to admit.

Comments