Tyler Mitchell on Richard Avedon, his photography hero

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When invited to select a photograph for the forthcoming show Avedon 100, at Gagosian’s New York gallery on West 21st Street, I chose an image of Richard Avedon and writer James Baldwin, together in one frame. The unassuming and lesser-known image is essentially a 20th-century “mirror selfie”. The two young men are looking at themselves in a looking glass framed by a decorative fireplace. Avedon holds a medium-format film camera at chest level. The fireplace is cluttered with a range of domestic objects – photographs, newspapers, ceramics, even a box of fabrics that appear to be bedsheets.

It was captured in the very intimate environment of Baldwin’s mother’s house in Harlem; Baldwin was 22 at the time, Avedon was 23 – the age at which I made history by photographing Beyoncé for Vogue, the first black photographer to shoot a cover. Avedon’s photograph was taken in 1946 – the year my father was born in Chicago. I can’t help but feel an auspicious connection to the work.

I look at this photograph of Avedon and Baldwin and see the many intimacies of a deeply collaborative friendship between two artists, one that was forged in high school and grew into such triumphs as the 1964 publication of Nothing Personal, a collection of photos and essays exploring American identity. Often, we are presented with images of these two figures in staged scenarios that position them as titans. And while they are titans, I love how pure and unguarded this moment is. Baldwin’s face is bursting with a rare teeth-revealing grin. It’s a moment of closeness and reflection. It reminds me of the significance of intimate friendships throughout the process of making and growing, creating and evolving.

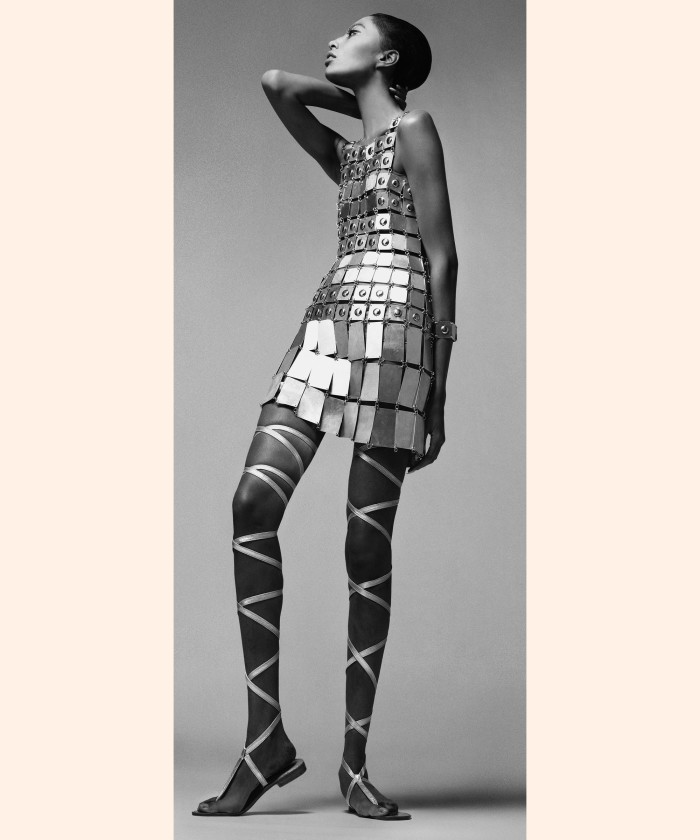

Avedon’s photographs have seeped so deeply into the cultural consciousness that they have become impossible to ignore. A great artist leaves an indelible mark on their medium, and Avedon achieved this. During my university days, I was a film and TV student, but my love for photography drove me to enrol in a class about making magazines. The class was taught by the great art director Yolanda Cuomo, who worked with Avedon from the early ’80s up until the end of his life in 2004. Among other things, they worked on campaigns for Christian Dior, Chanel and Calvin Klein. She shared many stories about him and his childlike curiosity for each and every little part of image-making. She said he was constantly excited by each opportunity, and every detail and process – whether the work was being published in the pages of Vogue and The New Yorker or exhibited at the Marlborough Gallery. I remember her telling us how he would examine the prints of his images in the back of a taxi with his keen eye. I imagined him grinning in the back seat, unable to wait until he got back to his studio to look at them.

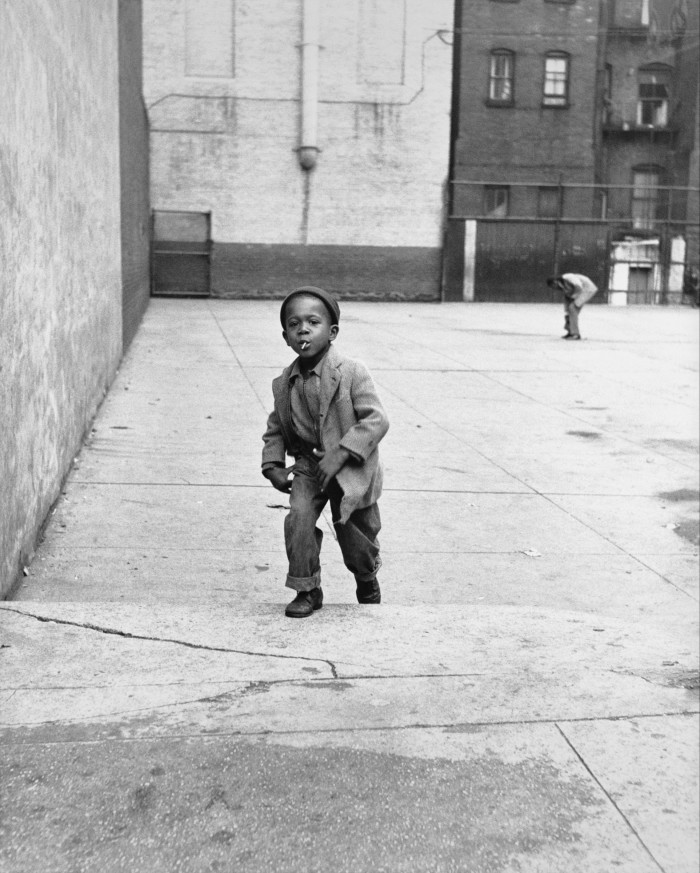

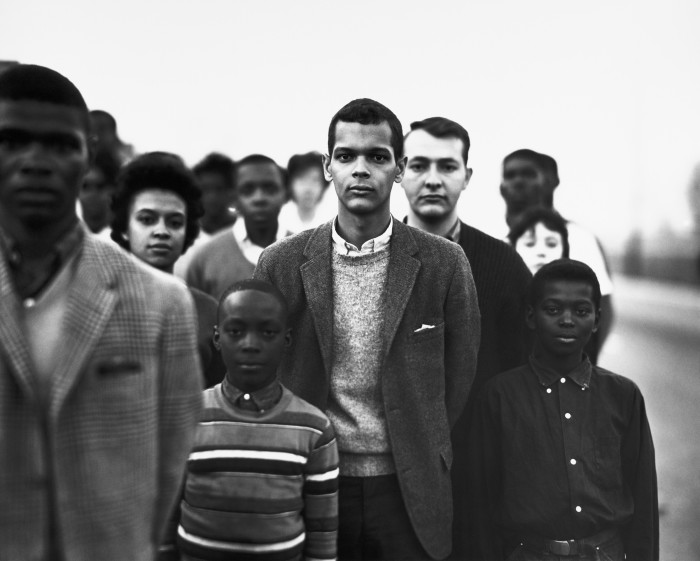

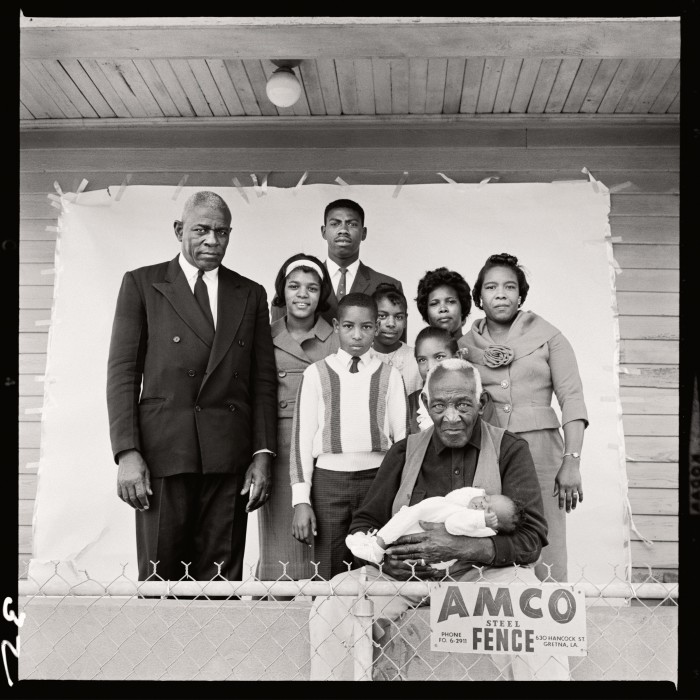

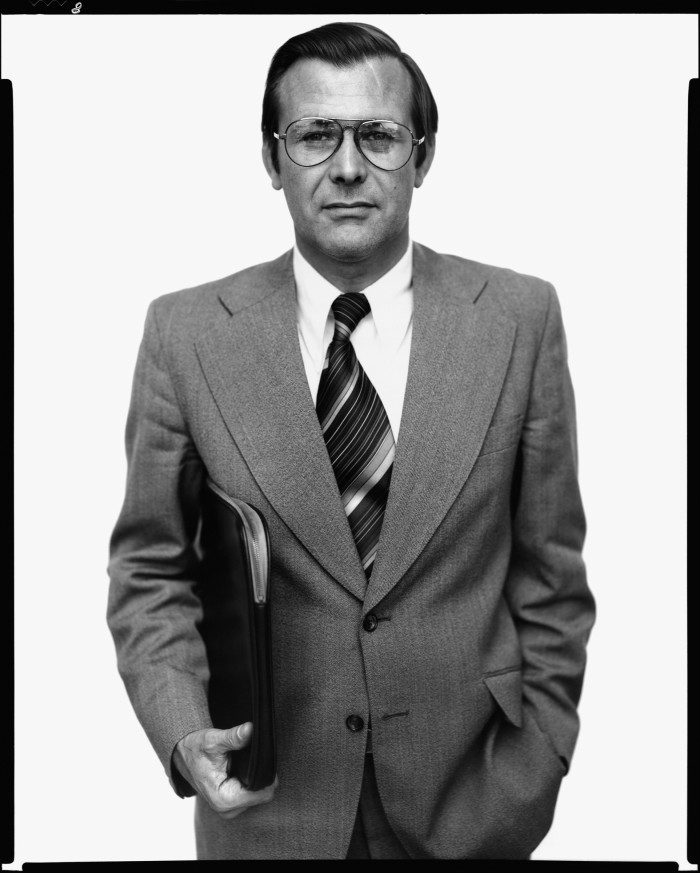

This rigour and zest for life is evident in the work itself. If a photographer doesn’t have these things, then what do they have? I imagine that Avedon’s wide range of subjects – whether the model Donyale Luna, James Baldwin or non-violent civil rights protestors in Atlanta – felt this teeming, magic energy.

Avedon’s pictures captured all walks of life, and many of his subjects were very different from his own. In looking at his work, I am reminded that to be a truly great photographer of people is to maintain a constant and genuine curiosity in others. Sometimes, in the hustle and bustle of life, this is much easier said than done.

But for all the vibrance he brought to portrait sessions, he is also quoted as saying: “My portraits are more about me than they are about the people I photograph.” Avedon was acutely aware of how the formal and technical decisions a photographer makes when taking someone’s portrait brings the viewer further from the “truth” and into a more slippery realm where the photographer and the sitter become one – if only for one moment. To make photographs is to make human spirits converge, shutter click after shutter click. This is precisely why I chose that image of Avedon and Baldwin for the exhibition.

Whether capturing an off moment or taking a highly staged portrait, Avedon understood the significance of crafting another person’s image in his own truest mind’s eye. He understood how doing so creates a truly unforgettable and human body of work.

Avedon 100 is showing at Gagosian, New York, from 4 May to 24 June, gagosian.com. Avedon 100 is published by Gagosian and distributed by Rizzoli, $100

Avedon – a life

1923

Richard Avedon is born in New York to Jewish parents; his father owned a women’s clothing store

1942

Joins the US Merchant Marine, taking ID card photos

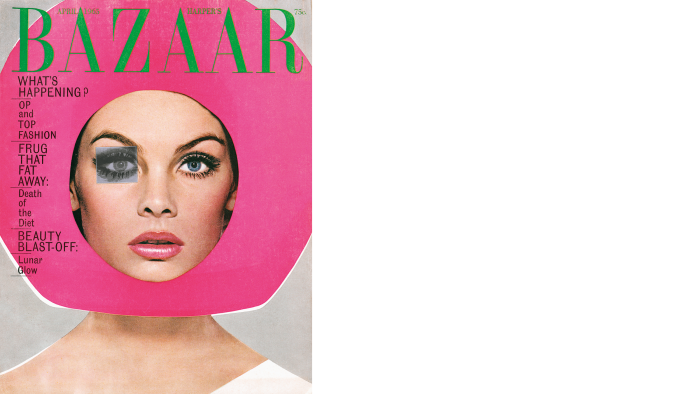

1944-1965

Works for Harper’s Bazaar with Alexey Brodovitch and Carmel Snow. Culminates with a guest-edited issue in 1965

1964

Nothing Personal, a book exploring the civil rights movement, is published by Penguin, with text by James Baldwin

1965

Joins Vogue, working with Diana Vreeland and Alexander Liberman. Later becomes lead photographer

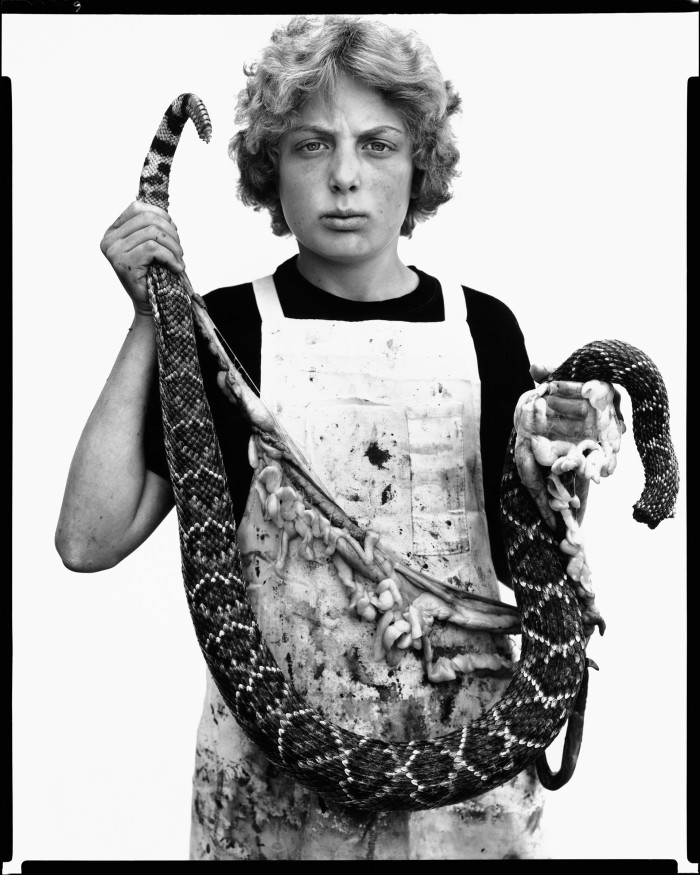

1979-1985

Works on a commission from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, culminating in the show and book In the American West

1992

Becomes The New Yorker’s first staff photographer

2022

Portraits retrospective opens at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

2004

Dies from a cerebral haemorrhage while on assignment for The New Yorker in San Antonio. According to model Lauren Hutton, “He died with his boots on.”

Comments