Olivia Laing’s garden of love

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 2020 I moved to an 18th-century house in Suffolk with my husband, the poet Ian Patterson. My task was to restore the garden, and his was to build a library for his 12,000 books – the remnants of a far larger collection, painfully relinquished when he retired as a Cambridge academic.

For 50 years the house had belonged to the garden designer Mark Rumary. He turned the walled garden into a plantsman’s paradise, filled with rare and unusual plants. Though it was only a third of an acre, it felt much larger because it had been divided so cleverly into “rooms”. Rumary died in 2010, and in the intervening years the garden had become wild and unbounded. Most of it, I realised on my first enraptured walk around, could be brought back to life. It needed restorative work – weeding, pruning, mulching, judicious removal and replanting – but the basic structure was sound.

The library garden was different. It formed the last of the rooms, tucked behind a yew hedge at the very back of the garden. In its heyday it had been consecrated to scented white plants, with a cherry tree in each corner and a circular green lawn. A good place to recover from a hangover, Rumary said. By the time we took over, this design had gone to ruin. The central circle was covered in a plastic tarp, the relic of a wedding dancefloor. It was surrounded by an impenetrable tangle of dying cherries and overgrown bamboo, box and laurel.

The west wall was formed by a Victorian coach house, complete with loose box. It was here that Ian proposed to build his library. Like the house, the building was listed, but we got permission to put in French doors, creating a library that opened onto the garden.

I wanted to make a garden suitable for a poet who’d spent his life with books – teaching, collecting, translating and writing them. Ian is decades older than me, and there was no way I’d be living in such a beautiful, enriching place without his generosity and love. During the years of the pandemic I was terrified I’d lose him. Now I wanted to create something for him – a garden like the margin of a decorated manuscript, inside which he could think and write.

Olivia Laing’s gardening address book

Trevor White Roses

The best source for species roses. trevorwhiteroses.co.uk

Riverside Bulbs

Suffolk nursery with an extensive range of unusual fritillaries. riversidebulbs.co.uk

Kevock Garden Plants

An incredible range of rare woodland plants, including species peonies. kevockgarden.co.uk

Woottens of Wenhaston

My local nursery, specialising in pelargoniums and irises, including the Benton varieties. woottensplants.com

Niwaki

Brilliant garden tools. I love the pruning saws and bright yellow snips for cutting flowers. niwaki.com

Because so little of Rumary’s original design had survived, I was liberated from the need to work as a restorer, and could instead be far more creative with my design. I sketched it out almost as soon as we arrived: a circular stone terrace that you stepped down to from the library door. At its centre I put a deep rectangular pond to attract the dragonflies and frogs, the bats and toads that Ian loves so much. I wanted to emphasise the feeling of damp seclusion, the intense privacy, but also to create a space that could be visited on even the grimmest winter’s day.

The cherries went, along with the dusty box and the bamboo, but I preserved the best plants, including a contorted medlar, a tree mentioned in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, as well as a wonderful forest floor of ostrich ferns, their green plumes exploding in late spring. Against this backdrop I wove a dense embroidery of plants, focusing on very old varieties, the species plants that so often are better for wildlife, with their simple, single flowers. I planted Rosa x cantabrigiensis, which was bred at Cambridge Botanic Garden. There was the highly fragrant Rosa rugosa “Roseraie de L’Haÿ” and wine-coloured species peonies, their flowers like tea bowls. I put in wood anemones, sweet woodruff and astrantia, known as melancholy gentlemen for their linen-coloured ruffs. All three plants appear in Gerard’s 1597 Herball. An Elizabethan would have felt at home.

I hate gut renovations of old buildings, and I wanted to change the garden with the same gentleness and subtlety as the library itself. As I worked on the borders, the roof was peeled back and insulated with sheep’s wool. Inside, the loose box became a reading room, the rusty manger rubbed down and re-enamelled boot-black. I echoed this make-do-and-mend approach outside, interplanting the ostrich ferns with deep red martagon lilies and pairing Mark’s medlar tree with a crab apple and a quince, a reference to John Keats’s St Agnes’ Eve feast.

Ian translated Proust, and I wanted to create Proustian flurries of scent. There was an enormous stand of Christmas box that made the garden exciting in January, providing cut flowers for the house. I added violets and Queen Anne’s jonquil, to my mind the richest, headiest of the daffodils. For summer days, there are old-fashioned Sweet William and more roses looped in curlicues against the walls – Bengal Crimson and Félicité Perpétue, with its nearly too sweet clusters of sugar-pink.

It’s the garden’s second spring now. The fritillaries and hellebores will be followed by a surge of blossom and then by Iris pallida and the roses falling open to the accompaniment of bees. Soon Ian will prop his doors ajar, so he can sit at his desk and feel as if he’s part of the garden, its observer and recipient. I don’t know how long we have together, but every day he is surrounded with a perpetual bouquet.

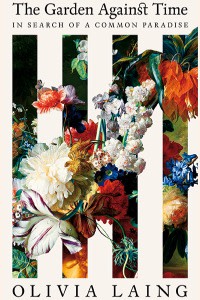

The Garden Against Time: In Search of a Common Paradise by Olivia Laing is published by Picador on 2 May

Comments