Why ZSL needs your help

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

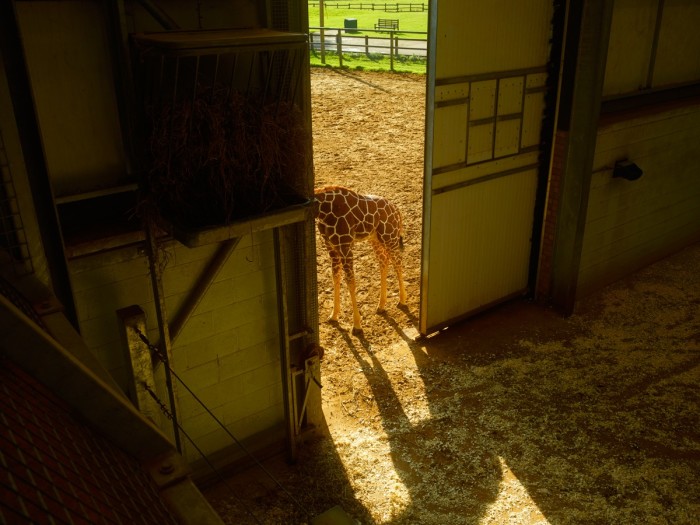

At ZSL Whipsnade Zoo, an hour north-west of London, the half-term visitors have gathered beside a large paddock for giraffe feeding time. It is a cold, bright afternoon, and two keepers hoist branches above their heads, offering them over the fence that surrounds the enclosure. Five reticulated giraffes amble towards them. The crowd laughs and coos, their attention particularly drawn to the smallest of the group, Khari, born at Whipsnade in April and a mere 8ft tall.

Suddenly a little girl gasps, stricken: “Look at his tongue!” Emerging from the giraffe’s mobile, bristly mouth is something purplish-black and prehensile – as long, perhaps, as your arm. In a matter of seconds, it has wound itself around the branch and stripped it of its leaves.

That’s the giraffe for you – so familiar and so very strange. The weirdness hardly needs to be spelt out. Some is visual: their hooves are as big as dinner plates, their eyes the size of golf balls. Some is behavioural: a giraffe can fell a lion with a thwack of its hind leg. But at Whipsnade, when one catches sight of a small, unfamiliar bag lying on the ground outside its enclosure, it initiates a mini-stampede. “They are quite highly strung,” sighs Ben, a taciturn 29-year-old keeper, as he watches his charges gallop away.

No wonder they are among the most popular presences in zoos around the world. They are endlessly meme-able, the stars of fashion magazines – and a baby giraffe? That’s Instagram gold.

But there is another side to the story. In the past few years, alarming information has started to emerge about the giraffe. The most recent data shows that their numbers have fallen by an estimated 30 to 40 per cent over the past 30 years. There are now fewer than 70,000 mature individuals living in the wild, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which three years ago changed the status of the giraffe as a species from “least concern” to “vulnerable”. The next step down would make it “endangered”.

It’s a few days after my visit to Whipsnade and I’m sitting opposite Sennett Day and Matthew Lowton, ZSL’s policy officer, in one of the buildings that make up the society’s sprawling Regent’s Park campus. The threats to giraffes come from many sides, but perhaps the greatest is the changing use of land in a rapidly developing Africa. Where giraffes could once roam freely over vast landscapes, today they find themselves increasingly hemmed in by human settlements. As towns grow and building work accelerates, trees are felled and the giraffes’ main source of food is depleted. “Climate change is also going to become more of an issue,” says Sennett Day. “You’re getting desertification and therefore there’s less forage for giraffes, so you’re shrinking that habitat even more.”

“Depending where the giraffe population is, there’s different causes for them being targeted or persecuted,” adds Lowton. “It can be from human-wildlife conflict, and in western and northern Africa there’s a regional bushmeat trade. In southern Africa you’ve got quite a lot of stuff being exported as trophies or the tibias and femurs being carved into lampstands or painted on. It’s not very well recorded, but there is evidence of it being utilised in local medicines – the muti trade – using the vertebrae or the brain.”

The extent of the global trade in giraffe parts – bones, pelts, meat – has not in the past been accurately measured. In August, however, the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species added the giraffe to its list of animals to monitor – another sign that the depletion of giraffe numbers is being taken increasingly seriously.

For millennia, humans and giraffes have rubbed along together, with the animals making appearances in Palaeolithic petroglyphs, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Ming dynasty scrolls and a plethora of Renaissance paintings. Lorenzo de’ Medici’s giraffe would stroll freely through the streets of Florence, snacking on bread and onions offered from first-floor windows. Their jolie laide charm bewitched Vienna, Paris and London in the 19th century, inspiring dresses, hairstyles and perfumes à la girafe. Even the Victorian hunters who shot them for sport were beguiled by the creatures, writing mistily of their long, feminine eyelashes and the “melting tenderness” of their eyes.

But one of the strangest wrinkles in the giraffe story is that we actually know vanishingly little about the animal in the wild. I found out just how mysterious they are last year, when I visited Namibia’s luxury Hoanib Valley Camp, which also hosts researchers from the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, the only NGO to devote itself entirely to the protection of the species across Africa.

Stephanie Fennessy, co-founder of the GCF, explained to me then that our understanding of the giraffe is years behind that of the other great land mammals. “One of the questions everyone asks us is how old giraffes get in the wild; we just don’t know,” she said. “There is so little known about their movements, how they use their habitat, and nobody knows anything about family relations.”

It was only three years ago that Fennessy’s husband Julian, a pioneering giraffe researcher, co-published a paper that fundamentally reconfigured our understanding of giraffes. Using DNA samples drawn from almost 1,000 animals across Africa, he and his colleagues established that there is not in fact one species of giraffe, but four – northern, southern, Masai and reticulated. Each of these species faces different challenges, and the prognosis for each is wildly divergent.

This is where ZSL comes in. “I guess if you’re a much smaller NGO, you have limited resources to be able to work across a whole landscape,” says Sennett Day. “I think ZSL’s key strength is that throughout Africa we’re very much working alongside the local governments. So the aim is that the government is able to protect its wildlife and ZSL is there to support it in any way we can to make that happen.”

ZSL works closely with the Kenya Wildlife Service in Tsavo West National Park, where numbers of Masai giraffe have fallen by half in the past three decades. “Tsavo really is, I think, the stronghold for many key charismatic species, the last chance for them to survive,” says Sennett Day. “We provide training, equipment and guidance on how to monitor wildlife within the park, as well as supporting with infrastructure, vehicles, all the things that you imagine in the day-to-day managing of a national park.”

New technologies are key: drones have revolutionised the tracking of animal populations across the landscape, while an app called Smart (the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool) allows the most effective deployment of rangers across protected areas. But ZSL also specialises in the human aspect of conservation, forging strong links with local communities. One major threat to giraffes is from indiscriminate snaring. “Communities will put out snares to catch small warthogs or dik-diks, but giraffes will end up getting caught in them,” says Sennett Day. “We support community scouts to go and collect snares. But we’re aware that the people laying the snares are poverty-stricken. They don’t mean to catch a giraffe – they just want to feed their families. So a lot of our work is trying to de-snare those areas, but at the same time support the communities so that they’re not so reliant on the national park’s resources.” This might be anything from setting up community banking schemes to helping people to switch to animal-friendly alternative sources of income, such as ecotourism.

The final redoubt for the giraffe is the zoo. It’s a hedge against the threat of extinction, a genetic bank that might allow for the reintroduction of animals into the wild. Across the world, stud books are maintained to ensure that giraffes are properly bred, avoiding mating between species and minimising the chances of inbreeding.

But more to the point, giraffes in zoos provide star power. When a giraffe birth was live-streamed from Harpursville Animal Adventure Park in upstate New York a couple of years ago, the feed drew 14m views over the course of the day. At Whipsnade, the presence of Khari is packing in the crowds. The idea that this beloved creature might be in trouble should be enough to stir anyone to consider the perilous situation facing wildlife throughout Africa.

After I leave the ZSL office, I walk through Regent’s Park. This is the place where I first saw a giraffe, elegant and serene, silhouetted against the singularly tall door of a singularly tall house. I glimpsed it sleepily from the back seat of my parents’ car, as we drove past London Zoo. Even then it seemed like a surreal dream – one minute there; the next, gone.

All funds raised from the FT’s Seasonal Appeal (campaign.zsl.org/ftappeal) will support the Zoological Society of London’s conservation and education work globally and in the UK.

Comments