Emerging economies forecast to shrink for first time in 60 years

Simply sign up to the Emerging markets myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Emerging and developing economies will shrink this year for the first time in at least six decades, according to the World Bank, underscoring the mounting economic toll from the coronavirus pandemic as it spreads across the world.

The bank’s forecast is that as many as 100m people in the developing world will be tipped into extreme poverty by a projected 2.5 per cent contraction in emerging markets’ gross domestic product, with incomes per capita set to shrink 3.6 per cent globally. The bank defines extreme poverty as an income of less than $1.90 a day.

In recent weeks coronavirus has spread from developed economies to major emerging nations including Brazil, Russia and India, and shutdowns to tackle the spread of the disease are taking an increasing economic toll.

“This is a deeply sobering outlook, with the crisis likely to leave long-lasting scars and pose major global challenges,” said Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, World Bank Group vice-president for equitable growth, finance and institutions.

“Our first order of business is to address the global health and economic emergency. Beyond that, the global community must unite to find ways to rebuild as robust a recovery as possible to prevent more people from falling into poverty and unemployment.”

Ms Pazarbasioglu said that between 70m and 100m people would fall into extreme poverty, based on the World Bank’s revised projections — a big increase on the 60m it had previously forecast.

The World Bank and the IMF have launched a series of rescue programmes to help countries grapple with the pandemic, and are co-ordinating plans for debt relief for struggling nations. However, some economists argue that the measures may not be sufficient to address the scale of the crisis.

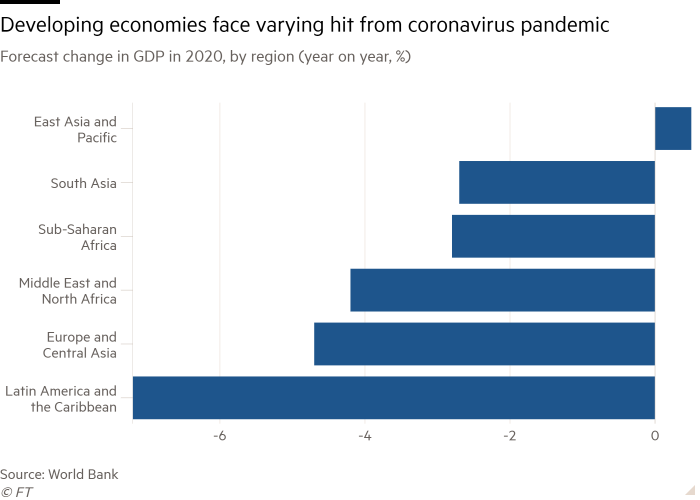

Economic activity in Latin America and the Caribbean will suffer the biggest drop, at 7.2 per cent of GDP, the bank forecast, while East Asia and the Pacific will be least affected, with an expansion of 0.5 per cent, although that would be its worst performance since 1967.

The economic toll is likely to be strongest in “countries where the pandemic has been the most severe and where there is heavy reliance on global trade, tourism, commodity exports and external financing”, the bank said.

Globally, the world economy will shrink 5.2 per cent this year, the bank said. Its projection is more pessimistic than the 3 per cent decline in global GDP forecast by the IMF in April, reflecting the growing economic impact of the virus.

The forecast assumes that restrictions on economic activity could be lifted by mid-year in advanced economies and “a bit later” in emerging markets; the bank said this would lead to a 4.2 per cent rebound in output next year.

But it warned that this scenario was “highly uncertain and downside risks were predominant, including the possibility of a more protracted pandemic, financial upheaval and retreat from global trade and supply linkages”.

If more negative conditions prevail, the bank said the hit to global GDP would be around 8 per cent this year and emerging market economies would shrink 5 per cent, with a sluggish global recovery next year of 1 per cent.

In the bank’s baseline scenario, the US economy is expected to contract 6.1 per cent this year, and the eurozone by 9.1 per cent. That is a more substantial contraction than the 7.7 per cent drop in GDP forecast by the European Commission last month.

Comments