The top 10 inflation crimes and misdemeanours

Simply sign up to the Central banks myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Tuesday

Hello and welcome back. The European Central Bank is decamping to Athens this week. No one is expecting any shift in interest rates by the ECB or by the US Federal Reserve when it meets next week. This might appear dull. But boring is good and I will be looking out for clues about future monetary policy.

Anything but boring will be a free webinar tomorrow where I will be joined by my fabulous FT colleagues — Martin Arnold, Claire Jones, Martin Sandbu and Colby Smith — to talk about the lessons we can learn from the battle against inflation over the past two years. It’s free for subscribers. Sign up here.

The charge list in full

One lesson for us all is to be flexible with our thinking on inflation. There is rarely one cause or one theory that explains everything. And it was when I was thinking about the webinar that I started to wonder what have been the worst crimes against data, logic and inference committed since inflation took off. Today’s newsletter is a chance to unburden myself a little.

Coming up is my top 10 list of offences in descending order of severity. This isn’t a definitive list and I’ve already had one write-in entry. Please email me with your own pet hates at chris.giles@ft.com.

1: The logical fallacy of long transitory

The adjective “transitory” to describe this inflation episode was officially “retired” by Jay Powell almost two years ago. The Fed chair knew he could not continue to use the word when inflation was already almost three times the central bank’s target level in late November 2021, with more price rises in the pipeline. At the latest count, US prices measured by the personal consumer expenditure deflator are 15 per cent higher than in November 2020. That’s seven years of 2 per cent target inflation in less than three. It was not transitory.

Advocates of the notion that the rise in prices was just a post-pandemic blip and required no response from higher interest rates went quiet for a bit. Rightly so. But now that US inflation is falling and relatively close to 2 per cent on some definitions (see later), they are saying, “See, I told you inflation would be temporary”. Who? You ask. Well, no less than the Nobel Prize-winning economist, Paul Krugman, who has recently coined the term “long transitory”.

Worse than being a contradiction in terms, it completely misses the point. Team Transitory’s core argument was that inflation would soon disappear, so no action on interest rates was required. The players argued against almost every monetary tightening. They can’t now claim victory when they had opposed measures that helped bring inflation down.

2: Persistent does not mean permanent

This fact about high inflation, lost on some, has infected quite a lot of thinking inside central banks. It lies behind much of the “higher for longer” talk about interest rates. The key thing is that inflation can also fall.

In the past week, we have seen some of this thinking from European central bankers. Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey warned that the last mile of getting inflation back to target would be the “hardest”.

Austria’s central bank governor last week saw the Israel-Hamas war as likely to stoke inflation in an apparent repeat of the 1970s, with the possible need for further interest rate rises. In truth, it’s highly uncertain what the consequence of war will be for inflation and knee-jerk hawkish responses do not help anyone.

3: Tying a false knot across the Atlantic

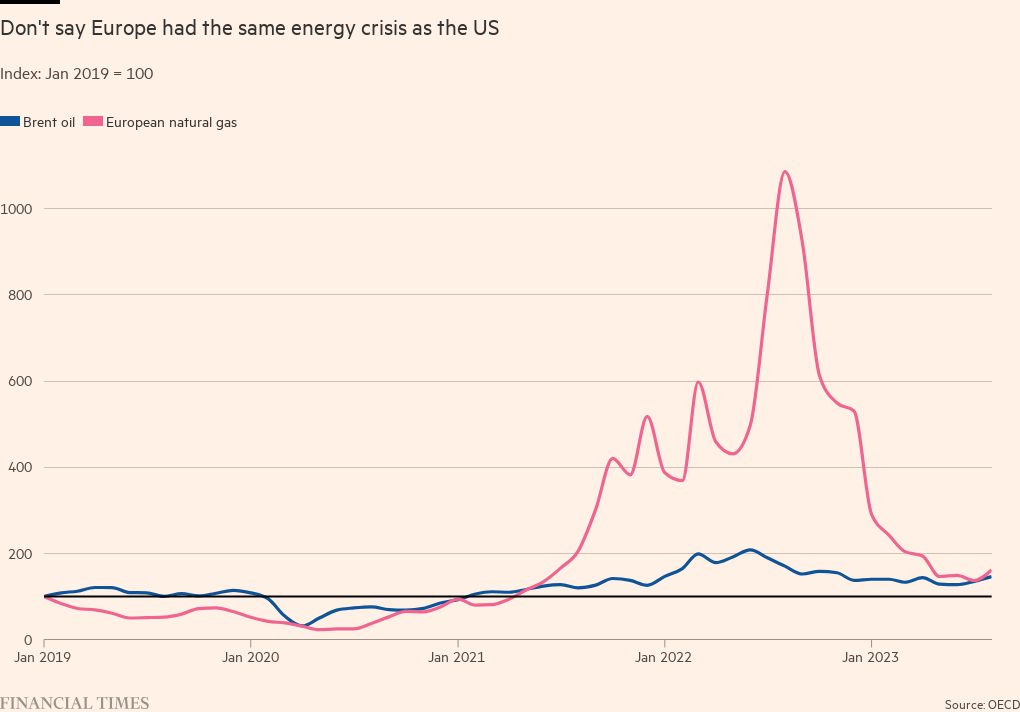

Just as it is wrong to doggedly hold on to an idea well past its sell-by date, it’s almost as bad to think that the causes of inflation must be the same in different locations. The classic error here is to assume US inflation has the same roots as those in Europe. It doesn’t.

Some forces pushing up inflation were global. Supply-chain bottlenecks and additional demand for goods during the Covid-19 pandemic affected advanced economies in similar ways. But the US had much more fiscal stimulus and, therefore, pent-up demand than Europe and a minuscule energy crisis in comparison.

Gas prices are regional while oil prices are largely global. BoE officials like to have a subtle dig at this fallacy, regularly producing charts showing that in the US, the main energy shock was a rise in global oil prices, but this was dwarfed in 2022 by the rise in European natural gas prices. The key elements are in the chart below.

4: Taking the Phillips curve too literally

I am going to pick on some members of the ECB’s governing council for the fourth category of crime. The bank’s governing council minutes for its March meeting quotes “some members” who criticised the staff’s forecast because it had the temerity to predict “immaculate disinflation” with inflation falling without a recession. This could not be possible, they suggested — and they are far from alone in that belief.

But, of course, ending inflation without a recession is possible. If a negative supply shock caused much higher inflation for a given level of unemployment, you don’t necessarily need to kill demand and drive up unemployment, following a fixed Phillips curve, to get inflation down. A positive supply shock can do the trick.

Luck isn’t always bad and, while I was critical of Krugman earlier, he has been absolutely on the mark here as the US data shows.

5: Money does not always matter

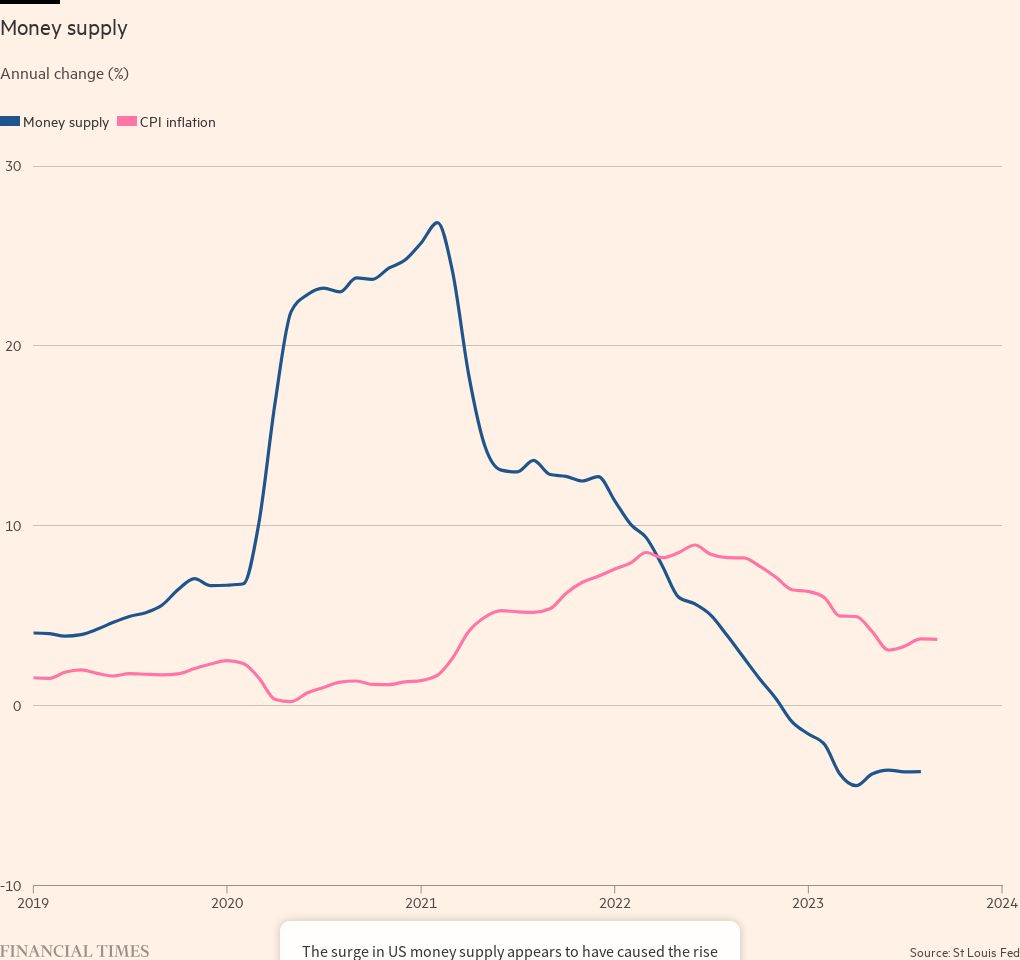

Monetarists have long been with us, trotting out the quantity theory of money that a rise in the supply of money always brings inflation with it. In the latest inflationary period, they have a strong case. That was the sole cause of inflation, says Steve Hanke, professor at Johns Hopkins University, who in a recent note slammed the Fed’s “reckless disregard for the only variable that counts: the money supply”.

All that sounds plausible, especially as M2 — a measure of notes and coins in circulation along with bank deposits — rose almost 27 per cent in the US on an annual basis in early 2021, just before inflation took off. Hanke is adamant there will be a recession in the country in 2024 because M2 has gone negative. If we scroll down and look at a much longer time period, the lack of clear correlation should make the rest of us a little more humble about predictions.

6: Selective statistics (bucket crime)

This offence is to choose a particular definition of inflation that supports your policy stance and make up some half-baked theory why this measure alone matters. Annual inflation measured by the US personal consumption expenditure deflator was 3.5 per cent in August, having come down from a peak of 7.1 per cent in June 2022.

Suppose you want to say US inflation is not improving; you then might choose something such as core non-housing services inflation, which was 4.5 per cent in August and has been hovering in the range 4.4 per cent to 5.3 per cent since July 2021. Powell made this argument in his Jackson Hole speech in August, saying this measure had “moved sideways”, adding that inflation would not be tamed until it came down.

But this measure is hardly representative of overall inflation targeted by the Fed, accounting for less than half the PCE inflation measure. Inflation can come down sustainably with core non-housing services price rises still elevated. The only reason to look at components of the total is that these might predict overall inflation better, not that they are a substitute target.

7: Selective statistics (time crime)

There isn’t a perfect time period over which to measure inflation. By convention, economists and central banks tend to use one year and have settled on a 2 per cent target for that period as defining price stability. But it isn’t sacrosanct. It is perfectly legitimate to examine monthly movements in prices or any other period, including the rise in prices since inflation took off (as I did earlier).

This free-for-all turns into a crime when people get too excited about one particular time dimension either as the only thing that matters or as a cast-iron guide to the future. I deserved a fixed-penalty notice for committing a misdemeanour here earlier this year when I suggested UK wage growth was stabilising because the latest data had been good. This came just before wages accelerated again.

8: Recency racket

This misdemeanour was suggested to me by Erik Nielsen, adviser to UniCredit, and I am grateful. No one should be making their monetary policy based on the latest inflation data (rather than a view of the future), he told me, because that “will surely end you up in the ditch”.

There is very little doubt that the BoE’s latest decision to pause interest rate rises in September was heavily influenced by the good inflation numbers for August that came a day ahead of its meeting. Did these really change the inflation outlook? The jury is out on that, but it was a troubling precedent to set. The MPC clearly bent with the wind of one set of statistics.

9: Greedflation grifting

Greedflation is a term that arose from the work of Isabella Weber, although she prefers the phrase “sellers’ inflation”. There can be no doubt that profit-maximising companies will seek to get away with price rises and a period of inflation often gives greater leeway to do this than other times.

But the evidence that this is the main driver of the recent rise in inflation is thin. The idea that companies will seek to take advantage of circumstances is also hardly radical. The ultraorthodox Bank for International Settlements made exactly the same point in its 2022 annual report, highlighting the dangers of slipping into a high inflation world. Banging on about greedflation is boring and so far from the whole story that it deserves to be called out.

10: Modern Monetary Theory madness

MMT claims “technical” underpinnings, but its key policy proposal has always been that much more public spending will be beneficial with no inflation risk. This was wrong. No more needs to be said.

What I’ve been reading and watching

Just after Jay Powell said the Federal Reserve would proceed “carefully” with monetary policy, signalling no desire for an imminent rate rise, financial markets decided to test the central bank’s resolve, raising 10-year government bond borrowing costs above 5 per cent. Fed forward guidance isn’t working.

One question about rising bond yields is whether these are a reflection of a better US economic outlook or a higher term premium. In this debate over things we cannot know, Unhedged asks the crucial question: is the term premium rubbish?

Yannis Stournaras, the Greek central bank governor, tells the FT that the ECB might be cutting rates by the middle of next year in a move that is bound to stoke simmering tensions within the governing council.

Over at Free Lunch, Martin Sandbu looks at Poland’s economic prospects following the victory of liberal economics in the election last week. Following Martin’s newsletter a key question hangs over the central bank — will Donald Tusk compromise its independence by removing its head, who supported the previous authoritarian government?

I was in Berlin last week moderating a panel of some of the world’s top academics on the future of work at the Handbook of Labor Economics conference. In a fascinating discussion, all agreed that maintaining tight labour markets was vital to employees’ prospects in the world of artificial intelligence.

Comments