Screen use can affect your eye health in digital age

Simply sign up to the Health sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The amount of time people spend looking at screens has grown dramatically, from using computers at work to watching television at home and being glued to a smartphone or tablet most of the day. It is a wonder how little trouble this appears to be causing our eyes.

The number of people complaining of tired, dry or sore eyes — some optometrists call this “digital eye strain” or “computer vision syndrome” — has risen but experts note that little reliable evidence exists of longer-term damage.

While smartphone and tablet use has greatly increased the average person’s exposure, says Chris Hammond, ophthalmology professor at King’s College London, “we are not seeing any epidemics of eye problems related to that”.

He does, though, recommend limiting children’s screen use because the phenomenon of pre-school children spending hours on phones and tablets is recent and effects are unknown.

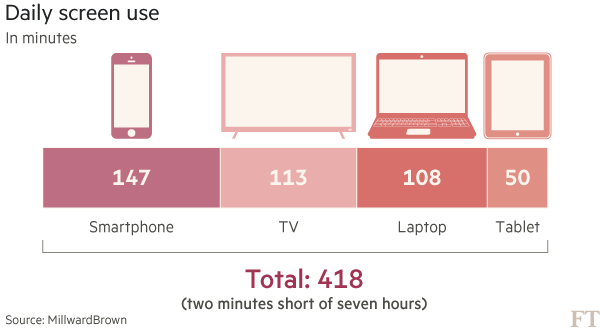

Globally, a 16-45-year old typically spends 418 minutes — two minutes short of seven hours — a day looking at screens, say researchers Millward Brown (see graphic). This comprises watching television, using the internet on a laptop or personal computer and viewing smartphones and tablets.

Smartphones have become the world’s largest screen medium. Combining smartphone minutes with tablet use, mobile devices account for nearly half of all screen time.

In many cases, people may spend longer on screens than they do sleeping. Figures range from 317 minutes in Italy to 540 in Indonesia. The average US user clocks up 444 minutes (480 in China, 411 in the UK).

One concern has been the effect of high-energy visible light — “blue light” — emitted by devices. Laboratory studies suggest that high levels of exposure can damage retina tissue. But Prof Hammond, who sits on the scientific committee of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists, says there is no evidence that low levels of blue light are harmful: “The energy level emitted by phones and iPads is extremely small. Even on a grey day outside, your blue light exposure is something like 30-fold more than looking at a tablet or a screen.”

Some evidence does show that using screens before going to bed disrupts the circadian cycle, or sleep-wake cycle, since blue light inhibits release of melatonin, the hormone that makes us sleep. Daniel Hardiman-McCartney, clinical adviser at the UK’s College of Optometrists, advises people not to use devices for an hour before they go to bed.

Another concern is myopia among children. A big increase in short-sightedness has emerged particularly in urban east Asia where children spend a lot of time reading and little time outdoors. Research results this year from the UK College of Optometrists and University of Ulster say 16.4 per cent of UK children are myopic, compared with 7.2 per cent in the 1960s.

Studies in Australia and the US indicate that spending time outdoors protects children against myopia. Some people suggest there may be a link between the condition and close-up work, though that could apply to books as well as screens. Prof Hammond says close-up work seems not to be the problem because indoor activity in sports halls does not protect children either, whereas outdoor activity does.

That leaves eye strain as the most common problem. Some 50-90 per cent of people who work at computer screens have symptoms of “digital eye strain”, say studies. This can include dry, sore eyes, headaches or blurred vision.

“We are now spending the vast majority of our day looking at things less than a metre away,” says Mr Hardiman-McCartney. “Our eyes are not designed to focus that close.”

Even a small defect in vision can lead to strain as the eyes seek to compensate. If your eyes do not work well together, looking at a screen all day can cause headaches. People also tend to blink incompletely when they stare at a screen, which can lead to dryness.

Productivity may be affected if eye strain causes workers to read more slowly or make errors. Research by the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Optometry has suggested that uncorrected vision problems could reduce work rate by up to 29 per cent.

Optometrists recommend frequent breaks or the 20-20-20 rule: every 20 minutes, look 20ft away (6m) for 20 seconds to give your eye muscles a break. Also, they say, make sure to take full blinks.

Mr Hardiman-McCartney says people need to sit upright at screens with eyes looking down at about 45 degrees, adjust brightness to the lowest level at which they can see a screen clearly and use a text size large enough to read. They should also have regular eye tests.

Comments