‘We don’t get paid for empty beds’: the crisis facing UK care home operators

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Mike Padgham, managing director of the Saint Cecilia’s care home group in Scarborough, was facing a stark choice. Did he accept new Covid-19 positive patients from hospitals to replace the 19 residents who had recently died, helping to safeguard 160 jobs and prop up the 30-year old business; or did he reject them — and sacrifice their fees — in the hope of restricting the spread of the deadly disease?

In the end, there was little alternative. With the cost of masks and staff wages outstripping income, and no new residents from the community accepting places, the care home boss felt forced to follow advice issued by the government in April to take in hospital patients, whether or not they had the virus.

“We don’t get paid for empty beds,” said Mr Padgham, who relies on the NHS and local authorities to pay fees for his elderly and frail residents. “We had to admit people with Covid-19 to stay afloat — but whether it’s right is a moral question.”

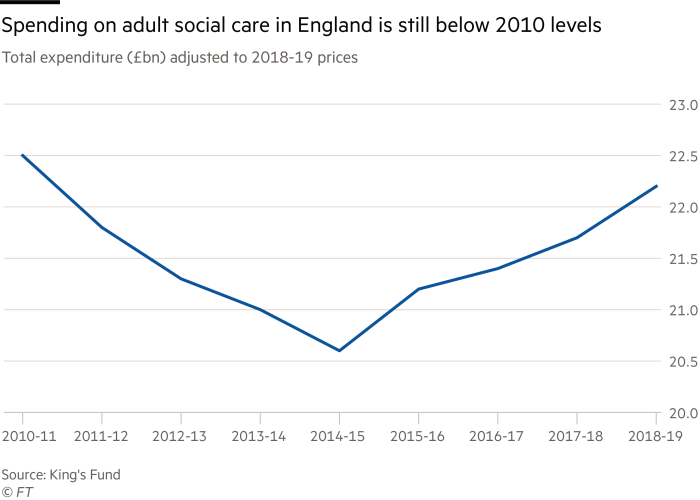

Thousands of UK care homes such as Mr Padgham’s were already under financial pressure before the pandemic hit. Britain’s decision to leave the EU and the rise in the minimum wage had increased staffing costs, while an £8bn drop in government funding for social care since 2010 had hit fees paid for residents, even as the number of over-65s grew.

Now coronavirus has not only turned care homes into incubators for the most deadly pandemic in generations, but left their operators battling to survive, raising the risk of further closures in a country that already had less capacity to house the elderly than the rest of Europe.

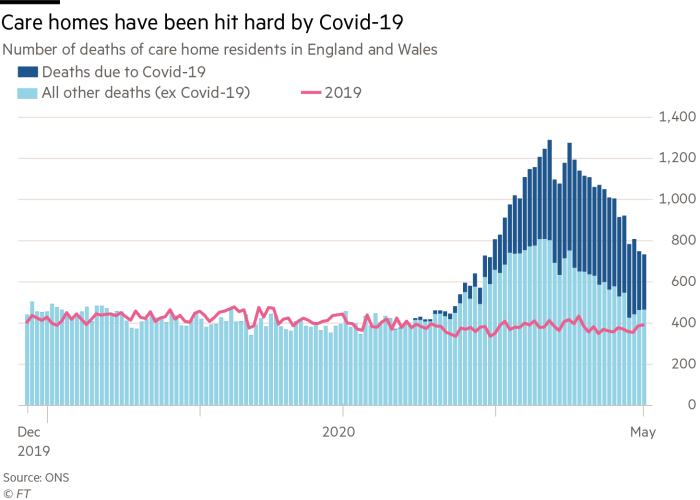

The 23,000 suspected coronavirus-related deaths in care homes in England and Wales and the vanishing queue of new residents has caused occupancy rates to fall by an average of 10 per cent already, eroding revenues that are unlikely to be replaced soon.

At the same time, the shortage of protective equipment means some care homes are paying more than £1,100 a day for masks, while agencies have raised the price of staff to as high as £90 an hour per person, taking costs to unsustainable levels.

The human and financial crisis has hit all parts of the UK sector — from large operators including HC-One, Four Seasons, Care UK and Barchester — to the thousands of small businesses that each own a handful of homes. It forced the government into a hasty withdrawal last month of official guidance that the care sector was “very unlikely” to be affected by the virus.

Nick Hood, an analyst at consultancy Opus Restructuring, calculated the drop in occupancy alone is costing the big four providers £707,000 a day based on reported 2018 turnover of more than £600m each.

This, together with the additional cost of equipment and staffing, is putting pressure on the big four’s ability to meet £239m in annual interest payments on a combined £2.2bn of debt — amounting to borrowing of £56,000 per resident a year.

Pete Calveley, chief executive of Barchester Healthcare, which runs 236 care homes, two-thirds of which have been infected with Covid-19, said its borrowings were small but there were concerns for other large providers “which have significant debt . . . and smaller providers with low cash reserves, which are at risk as occupancy declines and costs rise”.

Leonid Shapiro, managing director of consultancy Candesic, said the government would need to bail out the sector, which would take years to recover. “This is not a market that is going to turn round immediately after lockdown ends,” he said.

HC-One, which has also had coronavirus in about two-thirds of its care homes, warned in recently filed accounts that the problems were “so significant” that they could affect its ability to continue operating.

More than 923 people have died of coronavirus-related illnesses across its 328 care homes, while there are a further 5,105 suspected cases.

But like many of the larger care home chains, its complex, debt-laden offshore structure would make a government bailout hard to justify in a sector where income comes from taxpayers and people forced to run down their savings but where money leaks out in debt interest, dividends and management fees.

All four of the biggest operators have tried to sell in the past two years and failed to find buyers.

HC-One, which has 17,000 residents, has 62 companies, including 19 registered offshore, with the ultimate parent company based in the Cayman Islands. It paid a £6m dividend to shareholders in the year to September 2019 — down from a total of £48.5m in 2017 and 2018 — though only some accounts are publicly visible, making it impossible to tell whether or not more money is flowing out of the company.

Mr Hood argued that any support from government for HC-One and the large private equity-owned chains should be conditional on them bringing their financial structures onshore and banning dividends and other related party payments until any loans had been repaid.

HC-One confirmed it was in discussions with lenders, which it said were supportive and recognised the “underlying strength of the business”. In a letter dated April 29, it requested bailouts from England’s local authorities — and said at least one had offered to pay its usual 90 per cent occupancy rate. “We are confident we can overcome any challenge we face,” it added.

Four Seasons, the second-largest provider, has already been taken over by creditors — the US hedge fund H/2 Capital.

But by far the majority of the 400,000 residents in England and Wales are looked after by smaller care home providers, which lack the scale needed to subsidise the sharp rise in costs.

They have said that government fees were already too low to cover the price of care; many had already shifted their business to take only private-paying residents, who pay on average £12,000, or 41 per cent, more a year than those with state funding.

With fewer people qualifying for state support, about 70 per cent of care home residents have dementia or severe memory problems by the time they arrive, requiring more expensive round-the-clock nursing.

Mr Padgham, who also chairs the Independent Care Group, said the local authority paid Saint Cecilia’s £579 a week, while the true cost of providing care was at least £700 a week. He recently increased pay for his staff to above the national living wage — but has received no help from local authorities.

Although the government has granted £3.2bn to local authorities to help with the effects of coronavirus, providers said they were struggling to receive the money. Many have already cut the activities that staved off mental decline; during the coronavirus, residents are often confined to their rooms.

Robert Kilgour, of Renaissance Care Home Group, said he had “zero confidence” that any of the extra money from government would reach the front line in time. He expected more homes to shut, leaving families and local authorities scrambling to pick up the pieces.

Comments