Chinese students and political uncertainty drive rise in applications for financial courses

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Political uncertainty and the complex global economic environment have created more demand than ever for well-rounded finance graduates. This is good news for those teaching these subjects, as the numbers of people from around the world who want to study them are increasing.

The challenge for business schools offering masters in finance degrees is to give students knowledge of the latest trends and the most valuable skills they will need to operate in this fast-changing industry.

Alex Stremme, assistant dean for the programme at the UK’s Warwick Business School, says that it is precisely the complex nature of the challenges that lay ahead — such as the decision of the UK to leave the EU following last June’s referendum — that are driving the increased demand.

Prof Stremme says that we have not even begun to understand the implications of changes such as Brexit on the world of financial services, and that these will require “highly trained individuals with the intellectual maturity and independence that only postgraduate courses can develop”.

He adds that the sort of people the industry needs are those “who can explain the workings of a collateralised debt obligation to a layperson, while at the same time leading a debate about the pros and cons of quantitative easing”.

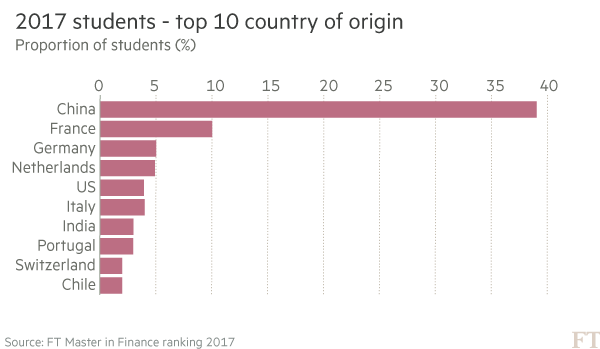

Top schools for financial training are helped by a rise in applications from emerging markets, particularly China. This year 50 per cent of all international students in the Financial Times’ ranking of global masters in finance courses are from the country.

It is some 12,170km from Tong Lin’s home in Handan, China, to the Louisiana campus of Tulane University’s Freeman School of Business, where he is currently midway through his masters in finance degree. But when the 23-year-old looks around the seminar room, he could be forgiven for thinking he has not left his homeland because all but nine of his 149 classmates are from China.

Applications to the course at Tulane’s Freeman school have risen by a third in the past three years, reaching 1,267 this year for about 200 places. “There doesn’t seem any sign of abatement,” says Ira Solomon, the school’s dean.

He adds there is little sign that US President’s Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric has had any effect on the number of overseas student applications. “We fashion ourselves as a global school,” Mr Solomon adds.

He says that his institution benefits from being close to the cosmopolitan city of New Orleans and 23 nationalities are represented across the school’s various masters degree programmes.

The attraction for Mr Tong, of studying at Tulane’s Freeman school, is not only its global standing, but the high salaries available in the US relative to other countries if he can secure a job as a financial analyst or researcher after graduation.

Mr Tong says he plans to return to China eventually and adds that his overseas work experience will help him to find a job when he goes home.

“Getting a job in China will be hard,” he adds. “But getting a degree from a top university in the US will make that easier.”

Freeman, where 94 per cent of this year’s cohort are Chinese, is an extreme example but more people from China are seeking to study abroad.

Chinese citizens account for more than 90 per cent of students on masters in finance courses at Leeds University Business School in the UK, the University of Maryland’s Robert H Smith School of Business, and Fordham University’s Gabelli School of Business in New York.

Business schools in the UK, which have historically performed well compared with schools overseas but which many fear could be undermined by the UK’s coming split with the EU, are reporting increased interest from foreign nationals.

Ironically, it is the fall in the value of sterling against other currencies after last June’s Brexit referendum that is being credited with enhancing the attractiveness of UK institutions.

At the University of Glasgow’s Adam Smith School of Business, Chinese students have replaced those coming from India, many of whom were put off by the ending of post-study UK work visas in 2012, according to John Finch, the school’s dean. While the school markets itself in China, many of the applications from that country come following word-of-mouth recommendations from former students, says Mr Finch. He adds that there are more than 400 Adam Smith alumni in China today.

Even as demand increases, schools are having to adapt what they offer to students to help them prosper in a world where employers want graduates with increasingly sophisticated skills.

Belgium’s Vlerick Business School has revamped its masters in financial management degree to include more “experiential”, hands-on learning, rather than just offering classroom teaching about corporate finance and econometrics.

For instance, the advanced corporate finance course’s end-of-year exam has been scrapped. Instead students write and present a “final masterpiece”, in which they must critically analyse and discuss a hot topic, such as the rise of shareholder activism.

Bjorn Crumps, the programme director, says: “They live it and they learn it. If they were successful once in a rather safe school environment, students will feel confident to replicate the analysis and apply the learnings in future professional contexts.”

The programme is now taught at Vlerick’s Brussels campus, closer to the regulatory and administrative centre of Europe’s financial markets and a short distance away from London, where all students take part in a week-long “learning trip”.

Again, the focus is on maximising practical experience, Mr Crumps says.

Comments