US companies opt for short-term debt in bet that yields have peaked

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Borrowers in the $10tn US corporate bond market are shying away from longer-term debt in a bet that soaring borrowing costs are unlikely to last.

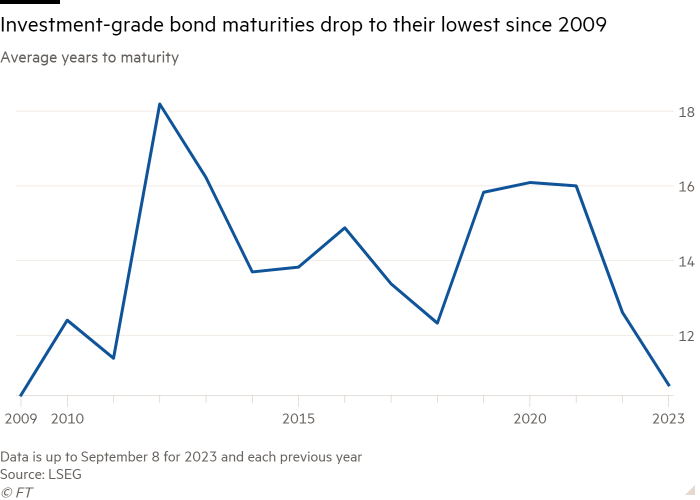

Corporate bonds issued so far in 2023 have come with an average 10 years to maturity — the lowest figure in more than a decade, according to data from LSEG that spans both high and low-grade debt.

With investment-grade issuance hitting its highest daily level since 2020 last week, the shortened maturities underscore how companies are adapting their funding strategies to a backdrop of drastically elevated interest rates. Many are hoping that borrowing costs will have fallen when they come to refinance their shorter-dated debt.

“For the most part, companies are preferring to borrow for three, five, seven or 10 years much more than borrowing for 30 years,” said Matt Brill, head of investment-grade credit at $1.5tn-in-assets fund firm Invesco.

“I think that’s just a function of how expensive it’s gotten for companies to borrow versus where it was just a year-and-a-half or so ago,” he added. “You don’t want to be paying this high coupon for any longer than you have to.”

Debt issued in the $8.6tn investment-grade bond market has had an average maturity of almost 10 and a half years so far in 2023, the lowest year-to-date number since the global financial crisis.

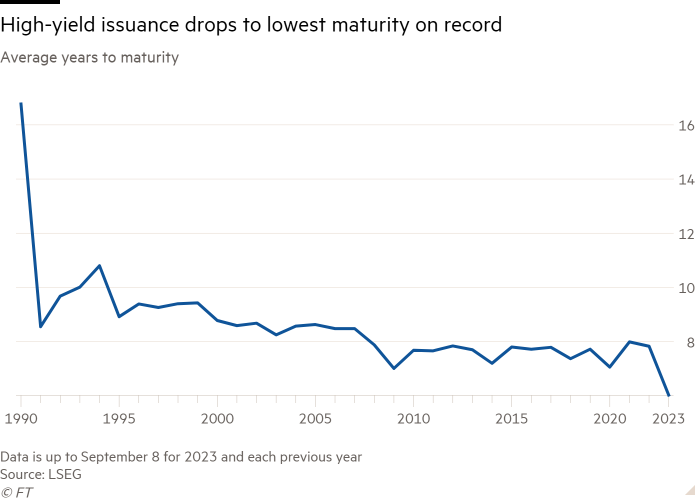

The trend is starker for borrowers in the $1.3tn junk market, where maturities have dropped from close to seven years and seven months in 2022 to six in 2023 — the shortest average tenor in records going back to 1990.

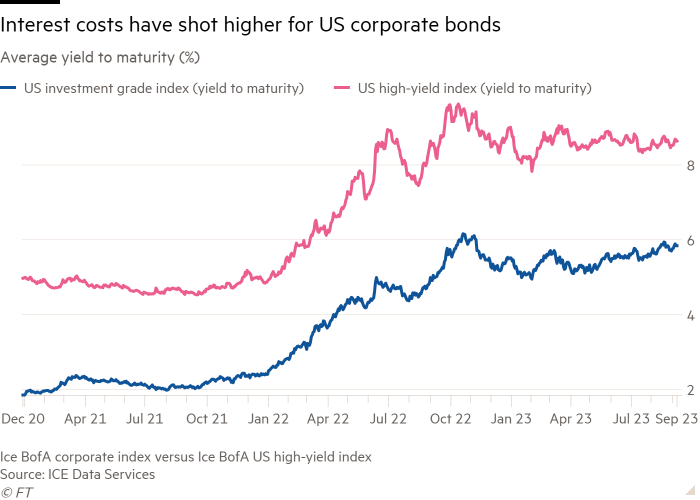

The shorter maturities come as US interest rates have climbed from near-zero early last year to a range of 5.25 to 5.5 per cent. In turn, investment-grade yields have shot to almost 6 per cent, from lows of 1.9 per cent in late 2020 when Covid-era stimulus was still washing through the financial system.

“Issuers are trying to stay shorter on the curve because absolute rates are so much higher,” said Maureen O’Connor, head of Wells Fargo’s investment-grade syndicate.

Junk yields now stand at 8.6 per cent on average, up from lows of 4.5 per cent in 2021 — a step-up in costs that analysts say has sparked both shorter-dated maturities and more asset-backed issuance in a bid to reduce interest payments. “Secured” debt, which pledges assets to lenders, has made up a record share of overall high-yield borrowing this year.

However, relatively few companies urgently need to refinance because many used the cheap money on offer at the start of the pandemic to push out debt payments. Overall bond issuance fell last year and is down again in 2023, with investment-grade sales 5 per cent lower at $942bn.

Junk bond issuance has climbed by a third to $108bn this year, compared with a particularly weak 2022.

Investors are divided over whether the Fed will raise rates one more time this year, but expect the central bank to gradually start cutting next year.

“I think most corporations feel like they’ll have a better opportunity to borrow for cheaper — meaning yields will be lower — in 2024 or 2025,” said Brill.

However, some market participants said shorter-dated borrowing reflected investor demand more than companies’ preferences.

Unusually, the Treasury yield curve has been inverted this year — meaning near-term bonds yield more than longer-dated bonds. So while borrowers issuing longer-dated debt will pay a much higher coupon than a few years ago, the cost may be less than for near-term debt.

Richard Zogheb, global head of debt capital markets at Citi, said there was a “push-pull” relationship between investors and companies, in which investors were drawn to shorter maturities, while, conversely, companies would prefer cheaper, longer-term debt.

“The investor base is saying, ‘if I can get five-year paper that yields better than 10-year paper, I’ll take the five-year paper’.”

“What we’ve ended up having to do is structure transactions with a short component and a long component and try to push the investor base into the longer component.”

However, Dominique Toublan at Barclays said maturity preferences depended on the type of investor. Some buyers of junk bonds, who are taking on additional credit risk, might favour the visibility of short-term debt, he said, while long-term investors such as pension funds “would love to be able to lock in these yields” offered by higher grade companies.

“These are yields they haven’t seen in 15 years,” he added.

Comments