The B-word Hunt failed to mention

This article is an on-site version of our Britain after Brexit newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

Good afternoon. Another busy week in Brexitland that has been dominated by a Budget with a distinctly fin de régime feel to it.

At points, as the Labour benches whooped and hollered at Jeremy Hunt, the chancellor’s usually beatific smile seemed to project more an air of resignation than the condescension (on matters fiscal) that he had presumably intended to convey.

This Budget had few surprises and (as Martin Wolf sets out masterfully here) was a grim advert for the UK’s pinball policymaking machine. The entire system for setting fiscal and industrial policy is anti-strategic, which is not unique to the UK or indeed to the Conservatives, but UK plc clearly needs to find ways to address this.

This being the Brexit watchers’ newsletter, you’d expect me to point out that there was a conspicuous absentee among Hunt’s list of reasons why the UK remains in the grip of a productivity slump that started after the 2008 financial crisis, with the result that taxes are rising and living standards falling.

In recent times, the UK economy has dealt with a financial crisis, a pandemic and an energy shock caused by war in Europe, said Hunt in his speech, calling these “the most challenging economic headwinds in modern history”. No mention of the B-word, then.

It’s a simple point, but one that bears repeating: if UK politics precludes either party from being honest about the Brexit-related challenges that face the UK economy, it will be much harder to convince the public of the steps necessary to fix them.

While the chancellor ducked the Brexit fallout, the Office for Budget Responsibility, which provided independent analysis of the UK’s public finances, did not.

“The effects of subdued investment, the energy price shock and Brexit compound the ongoing weakness seen since the financial crisis,” it said (my emphasis) in its Economic and Fiscal Outlook, published alongside the Budget.

Brexit, of course, is only one factor in a complex equation, but it is noteworthy that the OBR considers it a material factor and that the chancellor chose to ignore it.

I’m not suggesting for a second that Hunt doesn’t understand the damage Brexit has done and the bind it puts the UK in when it comes to attracting trade and investment — I’ve no doubt he’s painfully aware — it’s the inability to talk about it that matters.

And Labour is in something of the same boat. If it really wants to ‘roll the pitch’ for the kind of reforms that are necessary to help address the UK growth challenge, it will need to be clearer about the geopolitical cul-de-sac into which Brexit has backed the UK.

Because the OBR says that its original assumption that Brexit would lead to a 15 per cent reduction in UK trade intensity (imports + exports as a share of GDP) is “broadly on track”, citing several of the studies (Goldman Sachs, Niesr, Springford, Resolution Foundation) that we’ve covered in the newsletter of late.

And the outlook for UK trade over the next four years is also pretty gloomy, with export and import volumes expected to grow by just 0.3 and 0.1 per cent, respectively, between 2024 and 2028.

That matters because, as the OBR puts it:

“A decline in trade intensity plausibly lowers productivity because trade, among other channels, fosters competition and allows countries to specialise in activities where they are relatively more efficient.”

The OBR also notes the (under-acknowledged) fact that the effects of Brexit will continue to feed through over time: the UK is introducing its new border this year (on which more, next week) and the EU is diverging with the UK over time, with things like carbon border taxes creating more barriers to trade.

It cites a 2024 survey from the Office for National Statistics showing that around half of exporting firms and two-thirds of importing firms have reported extra Brexit costs; and a Bank of England Agents’ survey that “suggests EU trade frictions have weighed on export demand and may compound as new UK-EU regulations come into operation this year”.

That might explain why many of the comments from industry about the Budget were somewhat lukewarm, despite acknowledging that the government has taken some positive steps, such as raising the VAT threshold, making permanent the “full expensing” of capital investment against tax and a new plan to help boost manufacturing.

But Tina McKenzie at the Federation of Small Businesses said business was still facing rises in labour and input costs, warning “it’s not enough to just make ends meet, we need to make great leaps forward for the sake of the economy”.

At the Food and Drink Federation, Karen Betts said her sector was still saddled by a “muddle of regulation” and called for “joined-up, constructive government policies to shore up our strength and to create the conditions for investment”, which she said was “in short supply in this Budget”.

Steve Elliott at the Chemical Industries Association, a sector that has had a rough few years, also damned the Budget with faint praise, calling measures to support investment and growth a “step in the right direction . . . but, frankly, it’s a limited and long-overdue step”.

He added: “UK chemical businesses are facing huge competition from other parts of the world in terms of cheaper energy costs and more competitive and stable investment climates, so I remain at a loss over how we compete NOW.” (Elliott’s emphasis)

Brexit in numbers

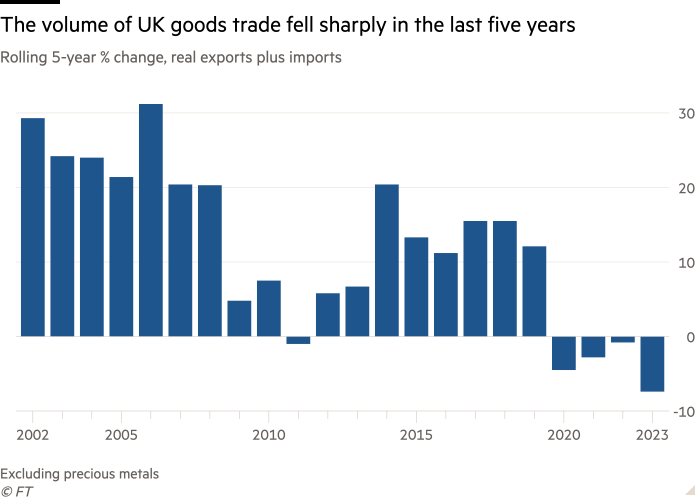

To unpack Brexit effects a little further, this week’s chart comes via my colleague Valentina Romei, who reported earlier this week on new data from the Office for National Statistics that showed that UK goods trade suffered its steepest five-year fall on record.

As noted previously, UK services exports are doing much better than goods, a fact the OBR in its analysis attributes to digitisation, companies using local affiliate workarounds in the EU and a weaker pound making the UK an attractive outsourcing destination for US professional services firms.

However, the goods numbers present some worrying signals for the UK, not least because nearly half of UK exports are still goods, and nearly half of those services exports are concentrated in London.

So while goods trade and manufacturing is becoming less important over time, it remains a key part of driving growth in the UK’s regions but also in supporting the industries of the future — medical devices, food technology, pharmaceuticals and green tech.

The pandemic demonstrated just how important advanced manufacturing capacity can be, and MakeUK, the manufacturers’ organisation, has welcomed last December’s £4.5bn Advanced manufacturing plan.

Some of the post-Brexit slump in exports can be attributed to ‘rules of origin’ issues, which mean that goods like textiles and footwear can no longer be imported into the UK and shipped on to Europe without attracting tariffs.

Exports of clothing to the EU fell by £3.3bn (61.6 per cent) compared with 2018 and footwear by £1bn (66.9 per cent) — but that’s still only a fraction of the total annual UK goods exports to the EU of £392bn in 2023.

But since this trade was based around importing and ‘hubbing’ out of the UK, it was arguably of limited value for the wider economy anyway.

Of greater concern is the part of the Brexit story highlighted by the Resolution Foundation think-tank in a compelling report last year entitled Trading Up, which set out how leaving the EU single market is likely to corrode the position of the UK’s high-value manufacturers in EU supply chains.

The combination of customs processes, regulatory divergence and new ‘Brexit 2.0 issues’ like carbon border taxes, are likely to make UK-based companies less attractive (all things being equal) as suppliers to EU-based companies.

Emily Fry, a senior economist at Resolution Foundation who co-authored the Trading Up report, says the data shows worrying early signs that in key advanced sectors — cars, chemicals, pharmaceuticals — the UK is performing poorly compared to G7 competitors.

She finds that between 2018 and 2023 total UK exports (volumes, to both EU and non-EU) of pharmaceutical products were down 11 per cent; chemicals and chemicals products down 19 per cent; and electrical equipment down 7 per cent.

“It raises the question about whether the UK is generally losing competitiveness in these sectors. Part of the story could be other supply chain factors, but the UK is performing pretty badly in goods trade relative to other G7 countries who have faced similar challenges. This underperformance could become a further drag on UK productivity growth.”

Seamus Nevin, the chief economist and acting director of policy at Make UK, says the challenges are not limited to Brexit — things like the scrambling of supply chains after Covid and now Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, a global semiconductor shortage and the Ukraine energy price shock, all play a role.

But Brexit, he says, clearly has had a localised effect for the UK, cutting the country out of onshoring programmes like the EU’s Green Deal, which has left the UK caught in the middle between the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s scheme.

Nevin argues that the UK has the power to hold its place in EU supply chains because it produces many world-leading products that EU industry cannot ignore, but nothing is helped by a policy churn-rate that deters investors.

“We’re the only advanced economy without an industrial strategy. And investment decisions run in seven or eight year cycles, but during that time you’ll have had almost as many business secretaries and as many growth strategies. That’s what’s really deterring long-term investment.”

Britain after Brexit is edited by Gordon Smith. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Comments