Maker of tiny satellites eyes a bigger role

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Space is big, as science fiction author Douglas Adams once wrote, but for Glasgow-based satellite maker Clyde Space, the key to extraterrestrial success is to think small. Very small.

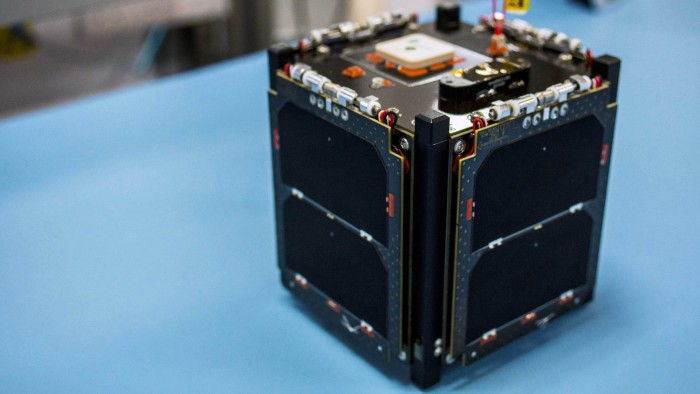

Clyde Space’s craft usually weigh about 4kg on Earth and are about the size of a loaf of bread.

Such modest packages can still have impressive capabilities: the new SeaHawk, a tiny satellite designed to monitor ocean colour, will boast better image resolution than a previous generation of spacecraft 100 times bigger, says Craig Clark, Clyde Space’s founder.

The SeaHawk will be able to transmit data at 40 mbps, 20 times faster than a 4kg satellite just five years ago, but Clyde Space is now looking at raising this to 100 mbps.

“You’re talking about an object that’s travelling at 8km/s [about 28,800km per hour], 600km above your head with a better downlink rate than your fibre-optic broadband into your house,” Mr Clark says. “It’s quite incredible the advances that have been made.”

Clyde Space is one of a wave of developers that are moving small satellites known as cubesats into the industrial mainstream, from their current niche for research and special missions, such as disaster monitoring.

The cubesats — so-called because they are based on combinations of cube-shaped units with sides of 10cm and 11cm — use standardised systems for deployment. This allows them to piggyback efficiently on the launch of a larger satellite or to be packed together on top of a dedicated rocket.

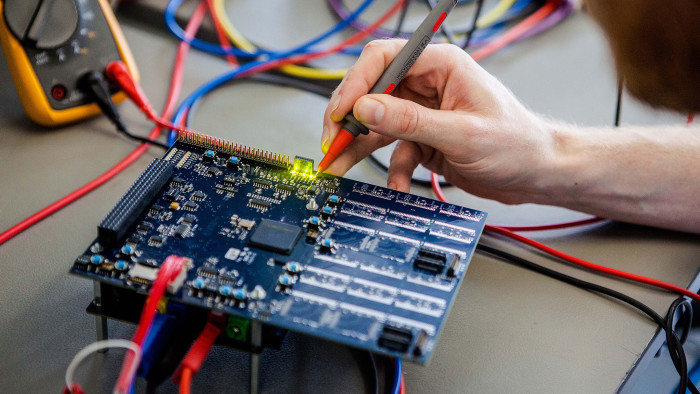

Each cubesat has to replicate the core systems of much larger spacecraft, including control and communications systems, solar panels and batteries.

The batteries are a particular challenge. The satellites operate in low-Earth orbits, sweeping in and out of sunlight 14 times a day and charging and discharging each time. While cubesat batteries can be designed to last five to seven years, most missions last three to four, with the satellite afterwards left to fall into the atmosphere and burn up.

Mr Clark, a former power systems engineer at industry pioneer Surrey Satellite Technology, set up Clyde Space in 2005 with backing from local private equity investors Nevis Capital and Coralinn. At first it only supplied sub-systems for other builders of small satellites, but in 2014 it built the UK Space Agency’s first national spacecraft, the UKube-1.

That led to a flurry of orders for other cubesats. Clyde Space, which has won a Queen’s Award for innovation, expects to have about 10 spacecraft launched in the next 12 to 18 months.

Clyde Space’s annual turnover is £6m, with exports accounting for about 70 per cent. The Glasgow company says it has enjoyed annual revenue growth of 60 per cent or so in the five years to 2017. This year, a bottleneck in satellite launches slowed the increase in turnover, but it remained in double figures and is expected to rebound. Earnings before interest and tax have been between 5 per cent and 10 per cent of turnover during the past four years, a level the company expects to sustain as it focuses on product development and expansion over the next half decade.

Cubesats of the size that Clyde Space builds sell for between $100,000 and about $400,000 depending on complexity and capability, with launches adding a further $200,000 to $300,000. In some years, the US military accounts for up to 30 per cent of the company’s business, but most sales are to civilian government bodies and commercial customers including a number of Silicon Valley start-ups.

The decision to set up the company in Glasgow was a personal matter. Mr Clark, originally from the nearby Scottish town of Cumbernauld, and his wife wanted to be close to family. In fact, the location has been a boon to the business, he says, with access to skilled people, excellent universities and the “extremely supportive” Scottish Enterprise, the government business promotion agency.

“Obviously, I’m a fan of Glasgow, I love Glasgow, I think it’s a great city, but I can honestly say that Glasgow’s a fantastic place to do business,” Mr Clark says.

Now he hopes the area might some day achieve a reputation for production of spaceships that emulates that of the famous Clyde shipyards that once built a large share of the world’s ocean-going vessels.

Inspired by Clyde Space, US satellite data company Spire has set up its European base in Glasgow and has built dozens of spacecraft there. Analysts say Scotland is already seeing the emergence of a “space cluster” with considerable potential.

Mr Clark cites forecasts of demand for thousands of small satellites in the next five years as reason to expect “hockey stick” market growth. Research by the UK’s Satellite Applications Catapult forecasts there will be about 1,700 small satellites launched globally from 2017 through to 2021, of which 1,500 will be in the 1kg -50kg range.

Clyde Space has been commissioned to build two satellites for Canadian company Kepler Communications, which plans a space telecom network to support the “internet of things”, which is digitally connecting previously separate devices.

Kepler says potential applications for the satellites range from tracking international parcel deliveries in real time to monitoring from space the temperatures experienced by workers operating in hazardous environments.

The first two-satellite mission is just a demonstration of the potential, says Mr Clark.

“Once that’s complete, the plan is that we’ll need to launch hundreds of these things.”

A list of this year’s winners and a guide to applying for a Queen’s Award are available at www.gov.uk/queens-awards-for-enterprise

Comments