Investors urge US Treasury to boost bond market liquidity with buyback scheme

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

US government bond investors are urging the Treasury department to intervene in the market, hoping for signals this week of possible buybacks after months of wild prices swings and poor liquidity.

The Federal Reserve’s aggressive increases in interest rates and quantitative tightening programme this year have amplified the drama in the normally staid $24tn Treasury market. Investors want the Treasury to provide clues of its plans when it makes its fourth-quarter funding announcement in the coming days.

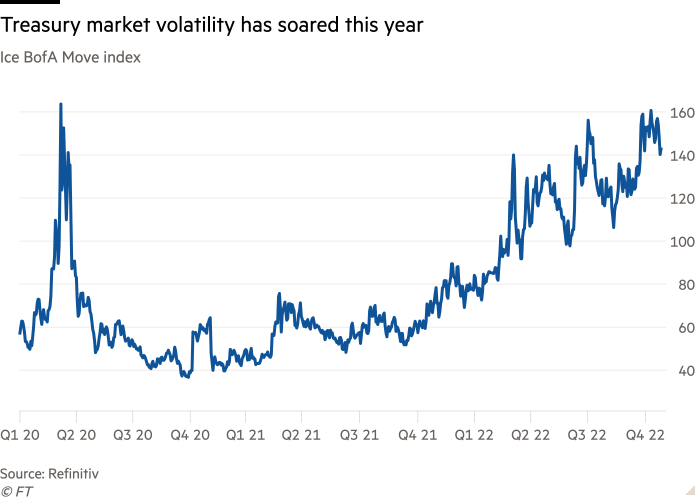

Treasury yields, which determine the US government’s borrowing costs and are used as benchmarks for prices across asset classes, have gyrated wildly in 2022. The volatility has made it harder and more expensive for investors to buy or sell Treasury bonds in a market that is ostensibly the most liquid in the world.

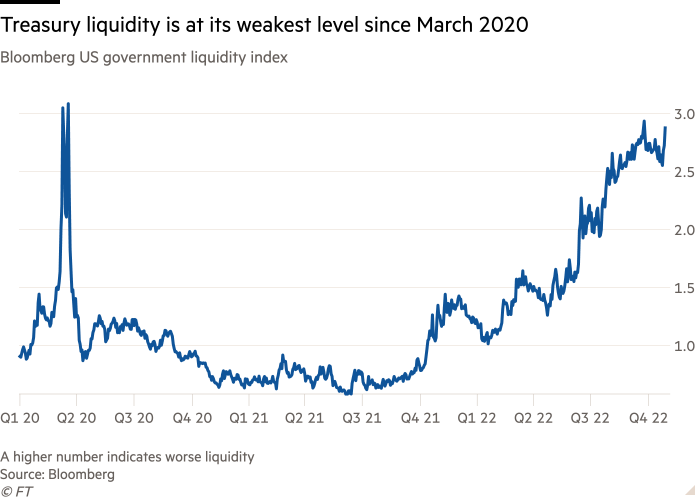

Treasury secretary Janet Yellen has said she is watching the situation closely. The Treasury department also asked primary dealers — banks that buy bonds directly from the Treasury — in a mid-October survey whether it should buy back older Treasury bonds, which are traded less frequently. The prospect of buybacks was first raised by the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee in an August report that highlighted the declining depth of the Treasury market, one measure of liquidity.

After discussing the results of that survey with primary dealers last week, investors, strategists and primary dealers are expecting the Treasury to include some details in the documents it releases this week. The Treasury on Monday will announce its estimated financing needs for the fourth quarter and its issuance plans on Wednesday.

The Treasury department declined to comment on the topic of buybacks.

While buybacks are not expected to be announced yet, even the prospect of that intervention could help buoy a market in which liquidity has deteriorated to the worst levels since March 2020. An announcement could also shore up faith after the turmoil that engulfed UK financial markets, during which government yields rose more than 1 percentage point in a matter of days.

“Buybacks will give the market confidence that there is a backstop if things get too cheap,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, a rates strategist at TD Securities, who expects buybacks to be officially announced in early 2023.

“Buybacks would allow banks to get [bonds] off their balance sheet when there are no buyers and would allow them to use their balance sheet more efficiently.”

This is just the latest in a string of liquidity problems in the Treasury market, which picked up following the great financial crisis. Post-2008 capital requirements made it more expensive for banks to own Treasury debt, so holdings relative to the size of the market have fallen.

Since then, hedge funds and high-speed trading firms have come to play a much larger role in the market, stepping in where banks have stepped back. As the structure of the market has shifted and the Treasury market has quadrupled in size, problems have proliferated, including the 2014 flash rally, the 2019 repo crisis and the March 2020 meltdown.

Buybacks, which were last done in the early 2000s, involve the Treasury department buying older Treasuries — so-called “off-the-run” bonds — that have been circulating in the market for longer and are harder to trade. Those acquisitions free up space on balance sheets for market participants to trade newer supply, and narrow the gap in yields between on- and off-the-run securities, a key measure of liquidity.

Having bought back old off-the-run bonds, the Treasury has to simultaneously replace them with new debt, which some investors think will be ultra-short, ultra-liquid Treasury bills, and some think will be new debt at the same maturity as that which was bought.

“They do have this perception issue with respect to Operation Twist,” said Joseph Abate, a managing director at Barclays, referring to a Fed policy used in 2011 and 2012 whereby the central bank would sell its holding of short-term Treasuries and use the proceeds to buy longer-term securities in an effort to lower interest rates and stimulate the economy.

To avoid comparisons to that programme, Abate said the Treasury should replace “similar maturity with similar issuance”, which would keep the average maturity of the debt constant.

One concern is that the Treasury programme will appear at odds with what the Fed is trying to accomplish in terms of rapidly tightening monetary policy by raising interest rates and shrinking its nearly $9tn balance sheet. Since June, the central bank has been reducing its holdings of Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities by ceasing to reinvest the proceeds of maturing securities. As of September, it has capped the so-called “run-off” at $95bn a month.

“The communications is the hardest hurdle to clear,” Kathy Bostjancic, chief US economist at Nationwide, said of the buyback programme. To overcome this, she said the Treasury needs to frame its purchases as “purely a tactical liquidity-driven operation” that is separate from the Fed’s operations.

In the end, such a programme could actually enhance the Fed’s ability to press ahead with its plans to shrink its balance sheet, given that it would significantly reduce the risks of a destabilising episode of illiquidity. Given the intensity of inflationary pressures, few things are likely to deter the Fed from ploughing ahead with tighter monetary policy, but a systemic financial market dust-up is one of them.

“We think it actually makes QT more likely to continue because if Treasury is able to move ahead and help with market liquidity, it gives us more confidence that the Fed can move ahead with QT,” said Meghan Swiber, a rates strategist at Bank of America.

Comments