The pros and cons of ejecting mobsters from City Hall

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Italy has a thing called cinque per mille. For every €1,000 a citizen pays in personal income tax, they can direct €5 towards a worthy cause.

It’s a voluntary scheme. A person can elect a non-profit when filing out their annual tax return, or can choose to pay into their municipality’s ringfenced social benefit fund. Tick neither box and the money goes to the Treasury. As of 2020 about one-in-three Italian taxpayers were ticking a box, which redirected nearly €500mn to social projects.

Cinque per mille can be seen as a test of faith in social capital, the fuzzy concept that a well-functioning society is built on trust relationships. A person who chooses to direct 0.5 per cent of their tax bill towards funding the local sports team or cat shelter probably feels generally better about their community than one who picks a national charity, for example, or who lets the option lapse. And since participation costs the individual nothing, these choices signal priorities that could normally only be explored through opinion polls.

Italy’s an interesting place to try a tax-based trust metric because it also has the Mafia, whose application of social capital has traditionally been somewhat uneven.

A working paper for Ca’Foscari University of Venice by economists Paolo Buonanno, Irene Ferrari and Alessandro Saia seeks to tie these threads together. Its title, “All Is Not Lost”, references a recent wave of anti-Mafia protests centred in the Puglian province of Foggia.

Since 1991 Italy has had the power to shut down any council where there is evidence of collusion between officials and criminal organisations. More than 300 had been shuttered by April 2021 under the legislation, mostly but not exclusively in the southern regions of Campania, Calabria and Sicily.

Buonanno et al conclude from a study of their tax returns that purging City Hall of mobsters results in “a significant and sizeable increase of social capital” over the long term.

Being told by government that your council has been wound up due to mob infiltration isn’t an obvious reason to put more trust in local institutions — and sure enough, the study finds that tax being routed into municipal social-causes funds drops sharply after dissolution. Yet the social capital value from a Mafia purge is still positive, it says, because incrementally more income tax goes to private voluntary associations.

In aggregate, the number of taxpayers allocating income tax to local non-profits increased by approximately 36 per cent after a purge. The number donating to the council fund fell by approximately 15 per cent.

Putting the ID code for a specific non-profit on a tax return is more of a faff than ticking a box, so rising private-sector donations indicate stronger social cohesion, the authors argue. De-mobbing also appears to spur the creation of more local non-profits (or maybe encourages more to gain cinque per mille approval).

Rooting out local corruption therefore “acts as a catalyst, effectively raising public awareness about the harmful influence of the Mafia on the community,” write Buonanno et al. “In response, community members are inspired to actively engage and participate, leading to the fortification of social ties and the cultivation of a collective commitment to enhancing the wellbeing of the community.”

It’s a conclusion that has some important footnotes:

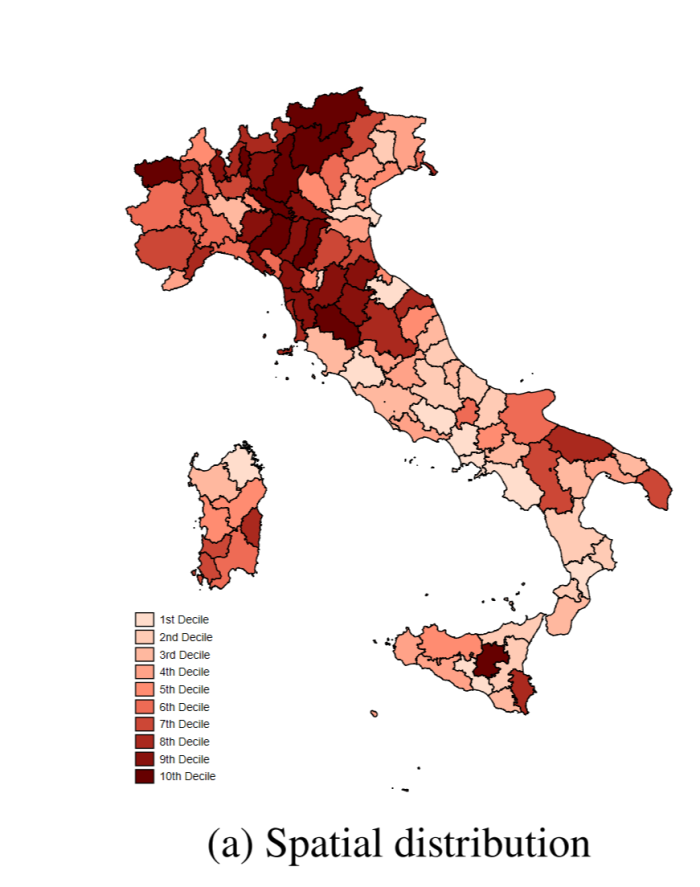

Setting a common baseline is difficult. Any mafia-related metric will inevitably be weighted towards Italy’s south, where centuries of neglect and brigandage have complex effects. The report’s tax-based trust heat map shows, for example, that community spirit in Sicily’s mob-ridden Enna commune is as strong as in the cities of Bologna and Bolzano, which regularly come top of Italy’s Qualità Della Vita survey:

Mostly, though, the heat map makes sense. To Enna’s immediate south is Caltanissetta, a legendary Cosa Nostra stronghold, whose social capital score is matched in the north by the Tuscan town of Prato (the tiny white fleck on the red streak that runs from Florence to the Swiss border). It helps to know that Prato’s textile industry has been infiltrated by Chinese mobsters.

Law-abiding citizens in a dirty council may become more wealthy once it becomes a clean council, if only because of lower extortion costs. It seems however that the removal of state-level Mafiosi doesn’t boost income tax receipts that much: the report finds only a “positive, but negligible” effect on total aggregate income and taxpayer count (as well as, peculiarly, a small reduction in taxable income per capita).

Because Mafia eradication isn’t quick or easy, it’s a study of long-term trends that’s susceptible to survivorship bias. Government officials are parachuted in to run disbanded councils for up to 24 months, after which elections are held that quite often return mob stooges to power, meaning the whole process has to begin again. To smooth the data, municipalities have to be certified clean for at least ten years and all repeat infections are excluded.

Not only are communities with strong trust networks likely to be better at resisting Mafia infiltration, the opposite may also be true. Local government by benevolent mobster could lend stability and foster a warped kind of community spirit. These and countless other variables make for some very wide error bars.

The sums distributed locally are small, with volunteer associations typically receiving less than €10,000 a year. Whether Italy’s micro-SME charity sector is free from corruption is a question for another time.

There’s a broad consensus on how organised crime is bad for democratic institutions in general and Italy in particular. For all sorts of reasons, measuring its effects on social capital formation delivers overall findings that are much less clear-cut.

Trust in elected officials is damaged whenever corruption is outed, the paper finds. Replacing criminal politicians with competent ones can help rebuild confidence, but that’s dependent on how the electorate votes. The big compensation found in the data is a more active private voluntary sector — but when compared against trust in civic governance, is pride in local sports teams and cat shelters more, less or equally important?

Maybe the safest conclusion here is that, even when it can be measured, social capital remains very very difficult to define.

Comments