How I Spend It: Eddy Grant on music, masonry and ‘magic spaces’

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When I meet a house I love, it’s like meeting a girl on the dance floor: there’s just something about it that says, “Oh, come on Ed, choose me. It don’t matter how much it’s going to cost, you choose me and I’ll see you alright.” I suppose I’m a recreation of my father. He was a trumpeter and I became a trumpeter. He was also a mechanic and he taught me lots and lots about motor cars but also, in the early 1960s, he got involved in supplying homes, especially for people from the Caribbean. He taught me to recognise a Georgian house, a Victorian house, an Edwardian house, and so forth. It became a driver for me and I’ve found out that with any money that I ever get, I just want to buy houses and do them up.

My first house came soon after our band The Equals had had their first major success in the mid-1960s. It cost me £7,250 in Kenton, near Harrow. As houses went, it was the bare bones, but it was a very happy home; and it’s very important to know when you’ve met a happy home, as opposed to when you’ve met somewhere where Dracula lived. My first, second and third child were all born there. It had apple trees and mulberries and blueberries and all kinds of berries in the back, so they had a really lovely beginning to their lives.

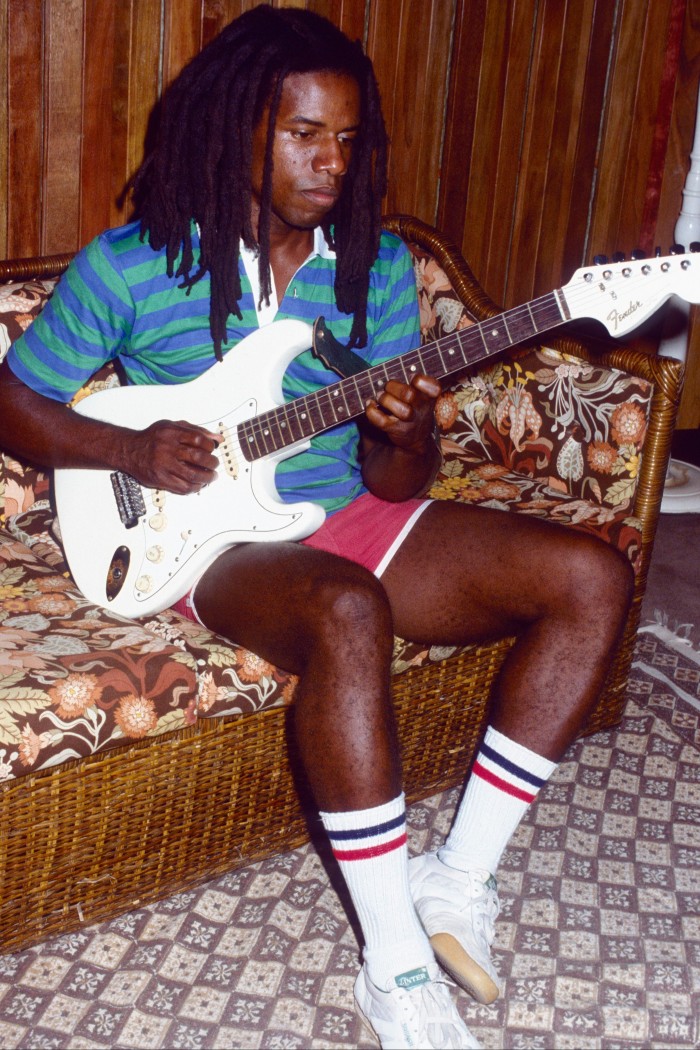

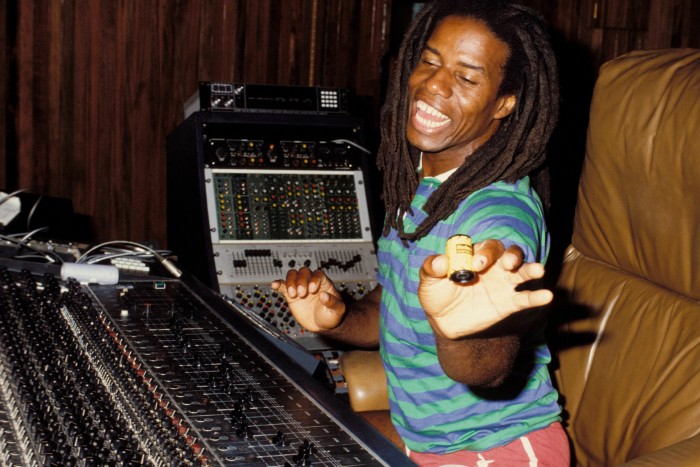

By the time I realised I was going to be having my fourth child, I’d started to go down on my luck; I was out of The Equals and monies weren’t coming in. I decided to set up a recording studio and borrowed money from the bank to buy what must have been the worst-kept building in Stamford Hill, north London. But I just fell in love with it. It was a massive Victorian house, with a coach house. I threw 28 skip loads of mud and rubbish out of that place, alone; alone, because I just didn’t have the money to afford help. That place was my baptism of fire. But it became the magic space. It really was a place of tremendous inspiration. Every day was a party. The artists were competing against each other to see who would be the first one to get that big hit out of there, like how it was with my man Berry Gordy in his Motown days. Of course, I was the last person and everybody was betting against me – “Ah, he can’t bloody sing with that croaking voice”. It’s only years after I got the hit that I found out that they were taking bets against me. Every black musician in England, I reckon, passed through there.

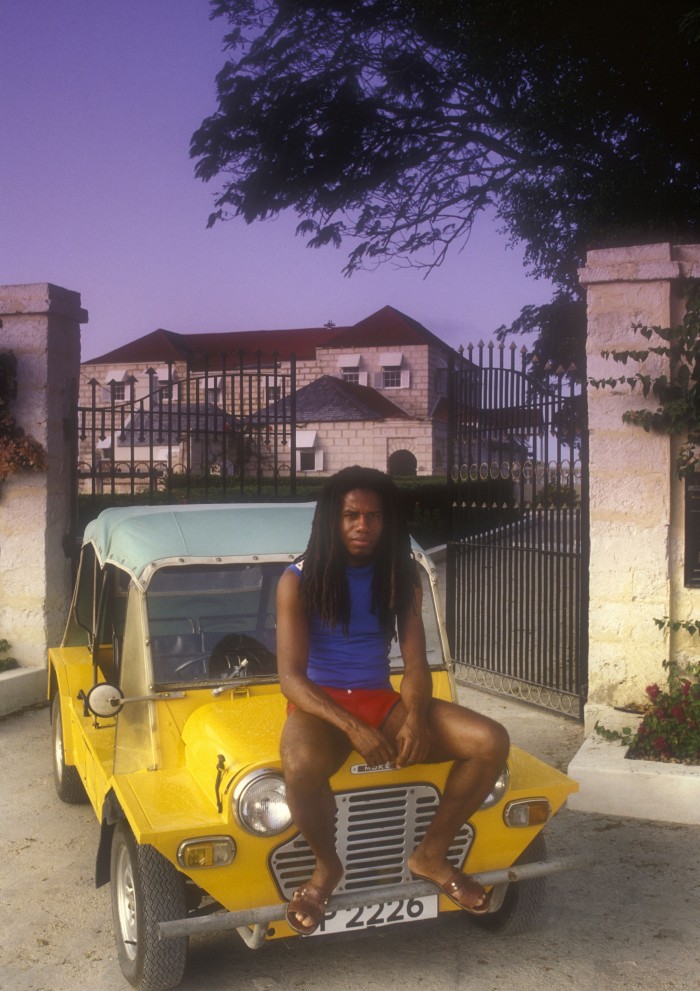

So that property set me on the road. But it was when I decided to move to Barbados in 1982 that I took on my biggest building project. I left my family behind in London for six months while I went in search of somewhere to build a home and a studio. Which is how I ended up buying the Bayley’s Plantation. When I found it, it was in such a shoddy state that everybody told me, “Oh God, you’re going to go down.” I lived very rough while I was building the studio. And we were recording in the place, while it was still being built, under the most horrible conditions. I’d sneak off to the cane fields to write songs. And the first one was “I Don’t Wanna Dance”. The second was “Electric Avenue”. The third was “War Party”. Almost as they appear on the album, that’s how I wrote them.

Today, people come from all over the world to see Bayley’s Plantation and to record here. Sting’s recorded here, The Rolling Stones worked on Steel Wheels here. I didn’t build it for other people, I built it strictly for me because I take so long to make records. Sting turned up out of the blue one evening and said, “Hi Ed, how’s it going? I’ve come to look at your studio.” And the first thing he did: he ran fully clothed and jumped into the pool. Then he went into the studio and started clicking his finger and then said, “Right, I’ll see you.” And off he went and jumped onto his plane. Then, a few weeks later, my wife said, “Ed, Sting wants to come into your studio.” He made The Dream of the Blue Turtles there, his first solo record. And it spun him out into a totally different orbit.

One day, a gentleman came by to see me, and said, “Do you know what you’ve bought? You have bought, singularly, the most important piece of real estate in Barbados.” And I said, “How the hell is that?” He says, “Heard of Bussa?” And I said, “No.” “Well,” he said, “he is the hero of this country. He led the island’s 1816 slave revolt.”

And it was really the luckiest place in the world for me. Every time I think about it, it brings a tear to the eye, because it could have all gone so far wrong. I didn’t know anything about this place. I’m just led by the spirits. They bring me to places. They take me from places. I love this house because of its history; because there’s an element of justice about it. I’ve been given something that, intellectually, has got endless value – value, as opposed to price. When I walk around this place, I walk around with reverence knowing that the great legs of the revolutionaries of 1816 that freed this country walked this same ground.

Eddy Grant’s latest single “I Belong To You”, from his album Plaisance, is out now

Comments