US junk bond market shrinks as rising rates put off borrowers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

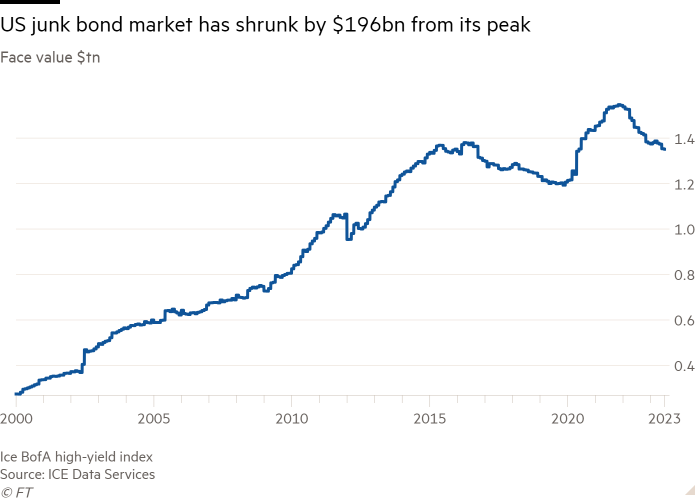

The $1.35tn US junk bond market has shrunk by almost $200bn since its all-time peak in late 2021, helping to anchor prices at levels that investors say could give false signals about the health of the world’s largest economy.

A steep rise in interest rates since early last year has helped deter companies from selling new bonds, while several companies have climbed out of the high-yield market into investment grade territory. Meanwhile, more borrowers are turning to private markets for fresh funds. Altogether, this has wiped 13 per cent off the total value of US junk bonds in issue since the record high.

That shrinkage has left investors with less choice about what they can buy and has pushed some fund managers to purchase bonds they might not otherwise have picked. That is helping prop up junk bond prices, even though many market participants continue to anticipate some form of economic slowdown.

“Dramatically lower issuance” is “really underpinning the asset class in terms of valuations”, said Andrzej Skiba, head of BlueBay US fixed income at RBC Global Asset Management.

“We’ve got cash building every month . . . You end up just buying the same stuff over and over,” added Dan DeYoung, high-yield portfolio manager at $584bn investment firm Columbia Threadneedle.

Those dynamics are threatening to give overly positive signals about the health of the economy, some investors believe. They are also potentially lining up the bond market for a sharper decline if the outlook darkens — particularly those of lowly rated companies that failed to extend the maturity of their debt when money was cheap.

“It’s asymmetric,” said Marty Fridson, a veteran high-yield investor and chief investment officer at Lehmann, Livian, Fridson Advisors. “These conditions can cause the market to be overvalued, but they don’t protect you from a huge sell-off and a gapping down in prices when things turn around.”

While a lack of supply has helped keep spreads low, “as we move into year-end, there are concerns that as recessionary headwinds start hitting the markets, we will see volatility pick up and spreads widen,” said Anders Persson, fixed income chief investment officer at Nuveen.

For decades, the high-yield bond market was the mainstay of risky borrowers, growing in size at an annualised pace of 8.7 per cent between 1996 and 2020, according to an analysis by Fridson. It later expanded to a record $1.55tn in 2021, as ultra-low interest rates sparked a dealmaking frenzy.

But issuance slumped in 2022, and while the amount of money raised has since climbed 30 per cent year on year to $90bn in the first half of 2023, this largely reflects refinancings. New borrowings in the first half of this year numbered just 39, totalling $33.2bn. That marks the lowest year-to-date deal count as of June 30 since 1995, Dealogic data shows, and the lowest by dollar amount since 2009.

“We are trading at probably tighter spreads than otherwise would be the case if we had a more vibrant primary market,” said Skiba.

Junk bond yields have shot to 8.69 per cent as of July 11 from a low of 4.53 per cent in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis. While most of that increase is accounted for by Fed rate rises, the spread — the extra yield demanded by investors to hold risky bonds over US Treasuries — has simultaneously widened out to 4.05 percentage points from roughly 3 percentage points.

Still, that level was narrower than at the start of 2023 and than the historical average of 4.58 percentage points for high-yield bonds outside of recessionary periods, said Fridson.

Investors note that economic indicators, including jobs market data, have so far been more buoyant than many had feared, despite the Fed’s aggressive tightening campaign, although figures on Friday showed that jobs growth slowed more than expected in June.

“That slowdown will manifest itself sooner or later,” said Skiba, speaking ahead of Friday’s jobs data, noting “the Fed’s rates being deeply in restrictive territory, and also the double-whammy from US banks — particularly regional banks — curbing lending activity”.

“I view the high-yield asset class, especially double-Bs, [as] fairly vulnerable if we do move into a recession that’s not just a very minor and shallow and brief recession,” said Adam Abbas, co-head of fixed income at Harris Associates, referencing the highest-quality rung of junk credit.

Ratings upgrades have also compressed the high-yield market, supporting prices. More than $81bn of debt has reached investment-grade status already this year, according to a Goldman Sachs analysis of major rating agencies’ actions, compared with $116bn throughout 2022. Just $15.6bn of debt had dropped down to junk as of late June.

For Lotfi Karoui, Goldman’s chief credit strategist, supply shrinkage this year “is entirely driven by rising stars exceeding fallen angels”, although many recent upgrades reflect a “backlog essentially of rising star candidates that should have probably been upgraded in late 2020, mid-2021”.

Toymaker Mattel, streaming giant Netflix, energy company Occidental Petroleum and insurer Enact are among the US companies that Moody’s has upgraded to investment-grade status in 2023.

Rating agencies move independently, with S&P lifting Netflix to investment-grade in late 2021.

More upgrades could follow, analysts and investors suggested, highlighting companies that were downgraded in 2020 and have not yet moved back upwards, such as car giant Ford.

High-yield bonds are not the only shrinking asset class. The $1.4tn junk loan market has also contracted this year for only the second time since 2010, with private credit again blamed for being a magnet pulling borrowers away from public debt.

UBS estimates that the private credit market has reached $1.55tn, up from $1tn in 2019. While drivers vary, some noted the greater certainty of execution in non-public transactions and fewer lenders involved.

Karoui said it was more of a “natural substitution” for loan issuers to switch to private credit than for bond issuers to do so. Still, “there’s no question that the depth of financing that is offered by private debt markets has increased dramatically”.

Additional reporting by Katie Martin

Comments