Foyles’ new flagship bookstore in London

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

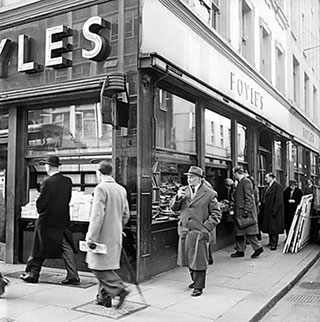

Charing Cross Road used to be built as much from books as it was from bricks. Outside almost every shop were barrows and ad hoc shelves loaded with second-hand volumes, while the windows behind them were stuffed with anything from pulp novels to rare tooled leather bindings. Evocative photos from the 1930s show men in macs browsing beneath tired awnings, lights glowing warmly in the night-time fog.

The West End’s book trade was, like everything in England, layered through with class. The posh bookshop was Hatchard’s in Piccadilly (established 1797); Charing Cross Road was for cheap second-hand stuff. At its centre was Foyles, billed a century ago as “the largest bookshop in the world” and still, at least in terms of the number of different titles stocked, the UK’s most expansive. The multilevel store, now the flagship of a seven-strong chain, once resembled a part of the Soviet Union. Nearby Collett’s might have been the left’s favoured bookshop but it was Foyles that retained the extraordinary Moscow-style triple queueing system: customers had to line up to receive a chit, then again to pay at an Edwardian-style till, then once more to collect the book from where they had started.

While this arrangement was designed to have as few booksellers as possible with their hands in the till, it failed spectacularly. Thefts were legendary, by both surly staff and customers (Elizabeth Taylor once lifted a copy of AE Housman’s A Shropshire Lad as she was being snapped by the paparazzi). Foyles was a kind of familiar chaos, with books piled up on stairwells and in cupboards. What you were looking for might just as likely be under a table as on a shelf, or at the bottom of a huge pile, layered with dust and sun-bleached. But it would, almost certainly, be there.

Today, a generation away from those arcane practices, the bookshop is reopening in a huge new building a couple of doors away from its historic home. I met up with Christopher Foyle, the latest family member to preside over the store, in a cosy timber-panelled corner room looking out on to Manette Street and Charing Cross Road. “This used to be my aunt’s sitting room” he tells me, referring to the formidable and eccentric Christina Foyle, who ran the shop like a dictator for more than half a century. “After she died [in 1999] it was left behind a locked door and shut away, filled with books and papers – no one even knew it was here.”

Foyle, double-breasted suit, colourful socks and silver hair, is a fine raconteur and charming company. He points out of the side window: “That was where Dickens based the character in A Tale of Two Cities.” In fact it used to be called Rose Street (once a hotbed of radicalism) and its name was changed to reflect its fictional inhabitant, Dr Manette. Books really do affect the physical fabric of the city around here.

Also present as we discuss the shop’s move to the former Central Saint Martins art school next door is architect Alex Lifschutz and Sam Husain, the chief executive with whom Foyle has worked since 2008. Why, I ask, did they need to relocate? “We’ve been on this site for over a hundred years,” Foyle tells me, “and the shop is higgledy piggledy and inefficient, it’s a maze. But of course customers like the nooks and crannies, the intimacy.”

That leads us to quite how an institution such as Foyles might be recreated. Lifschutz (of Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands architects) says simply: “It needs to be a place which allows things to happen.” This is an interesting interjection precisely because of its enigmatic vagueness. The problem here, not just with Foyles but with the entire trade, is that books are a dwindling market. Lifschutz’s comment recognises the uncertainty. “I don’t think any of us knows how this business is going to end up in 10 years’ time” says Foyle. “But the acceleration into ebooks has slowed. We have enough faith that people will continue to buy books over the next 50 years to build a new store.” He compares the advent of ebooks to the arrival of electric light: “It became the main source of lighting everywhere – but the candle didn’t disappear.”

The candle, in fact, became a luxury product, which is perhaps what is happening to books today. Walking around the old shop, you saw beautifully designed reissues, new translations of obscure central European authors, fascinating collections of essays and short stories, quirky travel guides. The book trade may be held up by the blockbusters – JK Rowling, Stieg Larsson, EL James et al, but Foyles’ market is different. “Normally the council wouldn’t have given permission for change of use from an educational building to a shop,” says Foyle, “but we were seen as a kind of cultural institution – and we’re devoting part of the building to a gallery.”

The old art school has its own history – a cultural resonance for the city every bit as worth preserving as that of the shop. The Art Deco building (still featuring its relief carvings of artisans and tradesmen) was completed in 1939 and the architects have restored its frontage, introducing a bronze main entrance and sympathetic steel windows. It sits halfway between institutional and industrial quite comfortably – a solid, massive presence.

When we enter the new building, Lifschutz points out the old stage in the atrium where the Sex Pistols once played. Now it will be an overflow area for the children’s book section. This was the school where fashion designers Alexander McQueen, Hussein Chalayan, Stella McCartney and John Galliano as well as artists Frank Auerbach and Gilbert and George studied, a warren of dingy corridors and paint-splashed, timeworn rooms. That interior is gone, replaced by a light, bright, open space with staggered mezzanines, so it is always possible to glimpse the next level, half a floor above you. There is no luxury shopfitting here, no confusion with the smooth artifice of a fashion store or a mall. Instead there are 4.6 miles of bookshelves, exposed ducting and lights in the ceilings and an emphasis on books as beautiful, tangible objects. It is a building of exceptional clarity, a fine series of spaces – even if I might have been happy to see something scuzzier, retaining an echo of the original Foyles’ chaos or the colour-spattered walls of the art school.

This is, of course, not just a place for books. Modern retailing, as we are endlessly told, is about the experience. And Foyles was in the vanguard of “added value”. The readings, book clubs, literary lunches and events have been happening here since the 1920s. With a spacious glass-walled new gallery overlooking the atrium and the reinstatement of Ray’s jazz café, Foyles and the architects have made every effort to make this Lifschutz’s place where things can happen.

Exactly what, however, is highly uncertain. The educational market in which the Foyle brothers started out (they sold textbooks from their failed civil service exams out of their mother’s Hoxton kitchen) is moving online; the second-hand bookshops nearby are struggling; Amazon’s discounting means people browse in shops then order later online (or even on their mobile devices in the store – “Booksellers really hate that,” says Husain with a grin). That lack of certainty is why the new store has to be big, flexible and seductive. It needs the stock to ensure that people still find what they are looking for, but also enough going on around the books to keep them coming in day and night.

“Architecture”, wrote Victor Hugo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), “will no longer be the social art, the collective art, the dominating art. The grand poem, the grand edifice, the grand work of humanity will no longer be built: it will be printed.” Hugo saw print replacing stone. Now print is itself giving way to the ephemerality of electronic information. In a city that has struggled to retain its distinctive trade districts, perhaps this combination of architecture, place and the printed word will allow Charing Cross Road to hang on just a little longer as the street of words.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture critic

——————————————-

A glimmer of hope on the digital plateau

There’s an old joke that the quickest way to become a millionaire is to start as a billionaire and buy an airline. In recent years, buying a bookshop might have performed a similar trick, writes Henry Mance.

Waterstones, Britain’s largest book chain, last reported a profit in 2009, losing £23m before tax in the year to April 2013. Foyles has not made a loss for five years but announced falling profits in its most recent results. For the UK’s independent bookshops, the picture is much bleaker: a third have closed their doors over the past three years.

The future of bricks-and-mortar bookselling may now hinge on two factors: first, how quickly readers shift to ebooks; and second, whether there is an alternative to Amazon’s low-price, high-convenience model.

The good news for Foyles and others is that the shift to digital has slowed. Sales of consumer ebooks rose 373 per cent in money terms in 2011, according to Britain’s Publishers Association; growth waned to 134 per cent in 2012 and just 18 per cent in 2013. In the US, ebook sales growth last year was below 4 per cent, the Association of American Publishers reports.

Some see such figures as evidence of the resilience of print. “You’d be quite surprised by how positive many booksellers are,” says Tim Godfray, chief executive of the UK’s Booksellers Association. “We feel we are in a better place than a year or two ago.”

Others are unconvinced that ebooks are beginning to plateau, with a report this week from PwC predicting that they will account for more than half of UK consumer book sales by 2018. And 2013 was also a fairly miserable year for physical books in the UK. Publishers sold 380m copies, 9 per cent less than the previous year, and down from 464m in 2009.

Amazon accounts for an estimated near-half of all new physical book sales in the US and the UK, though there are no reliable figures. (Similar guesswork puts its share of ebook sales above 70 per cent, based on the strength of the Kindle.) Its negotiating power – now on display in a stand-off with publisher Hachette – means it can offer prices that bookshops can’t match.

Hence many bookshops are looking to become more rounded cultural centres. This year, Robert Hiscox, former deputy chairman of Lloyd’s of London, helped rescue a bookshop in Marlborough with the plan of making it a local arts venue. The shop’s new management described his actions as “philanthropic”.

As an insurer, he hopefully knows the risks.

Comments