Best in glass: the new wave of makers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Glassmakers have long kept their cards close to their chests. In medieval times, Murano glassblowers were forbidden by the Doge to leave Venice, lest they let slip their well-guarded secrets. Today, a cross-fertilisation of ideas is causing the global glass scene to bubble with creativity, as makers move between hubs of experimentation – from Seattle’s Pilchuck School of Glass to Canberra Glassworks in Australia.

“Each area has its own specialisation, so makers visit to learn and hone that skill,” says Daniella Wells, galleries liaison manager at Collect, the London craft fair that in February hosted six glass galleries – the highest number to date. “What we are seeing now is a perverting of tradition. Glassmakers will look at the knowledge of, say, the Czech Republic, learn from it, then do something quite different.”

Trine Drivsholm, for example, is a Danish artist who learnt to blow glass in the Venetian style at Pilchuck. “But I never really used the Venetian style,” she says of her work, which instead draws on her “Nordic cultural background”. Most recently, it is plants that fuel her creative motor. Her sinuous and colourful blown-glass Cactus pieces are dotted with soft spikes, while last year she unveiled the new Botanical Structure series at London gallery Adrian Sassoon, which takes plant cross-sections as its starting point. “I wanted to create something poetic rather than scientific,” says Drivsholm, whose pieced-together forms suggest organisms viewed through the lens of a surreal microscope, their silky surfaces laboriously smoothed with grinding powders.

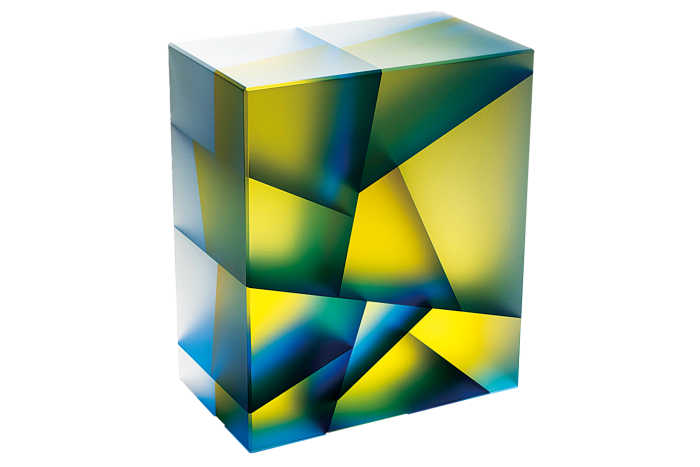

The natural sciences also make their way into the work of South Korea-born, Illinois-based Jiyong Lee, who is one of the 30 finalists in next spring’s Loewe Foundation Craft Prize. His series Segmentation is based around the structures of biological cells, their nascent geometrical shapes translated into crisp, mathematical structures in hues that shift from translucent to opaque.

Other innovators are turning to man-made environments for inspiration. “I respond to the mundane and everyday – tiling patterns, the undercroft of the Hayward Gallery, the façade of a tower block, the grates of drains,” says Royal College of Art graduate Joshua Kerley, who is also spearheading a trend for mixing glass with other materials. His 2019 series Fletton combines flowing glass shapes with raw chunks of brick, while Divergence fashions cork and pâte de verre into forms that bear a mischievous resemblance to broken drainpipes. Grainy pâte de verre is also used to make his Composite lidded jars, which use the enchanting technique of mixing glass paste with a foaming agent. In glorious sugary pastel colours, these neat cylindrical vessels look almost liquid, thanks to the illusion of a frothy, bubbling crown.

In Germany, Pia Wüstenberg has been combining glass with ceramic, metal and wood in the classic-with-a-twist Stacking Vessels she has been creating since 2011. Most recently, she’s added cut glass to her palette, resulting in the “rough and refined” Sculpt series that, literally, add another facet to her sought-after, large-scale works. And in Prague, Milan Krajicek subverts his nation’s historic glass practices by creating an inverse of traditional Czech lead crystal. “I used the mass removed by the glass-cutter as the basis of my work,” he explains. “Symbolically speaking, that which usually disappears irrevocably becomes the basis of something new.”

For Elena and Margherita Micheluzzi, the traditions they are revisiting are truly close to home. The daughters of Massimo Micheluzzi, one of the world’s most renowned designers of Murano glass, grew up watching their father work with blowers in the furnace. “I realised there was a huge demand for Murano drinking glasses and suggested it as an opportunity to my father,” explains Margherita. “He said table glasses were not part of his vision and suggested we design them ourselves.”

What they came up with is a collection of traditional glassware and vases that both honours and plays with their own heritage. In subtle transparent hues – pale gold, rose pink, aquamarine – the designs are spare and clean, with patterns and curves created by cold-carving into blown glass. “They are smaller, more domestic than my father’s objects, and perhaps more feminine,” adds Elena. “That’s in keeping with who we are.”

Collectors are welcoming this new wave of makers. “Ceramics have been in the limelight over the past few years,” observes Wells. “But Collect 2020 was a real step change in ambition and experimentation in the glass scene. It feels like collectors are open to living with more complex pieces.” And contemporary glassmakers are answering the call with aplomb.

Comments