Managing your money for a lifetime of financial security

Simply sign up to the Workplace pensions myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

My parents-in-law, now in their late eighties, have enjoyed a long and happy retirement. As their physical health has declined, however, I have had to take over the day-to-day management of their personal finances.

As is typical for many of his generation, my father-in-law always handled the money. I have a lot of respect for his ability to manage his finances to this point, so I felt slightly uneasy reviewing his bank accounts, paperwork and spending.

I was surprised to find that he had quite a large amount sitting in his bank account, earning no interest. After moving these funds to an interest-paying account, I reviewed their income and expenditure.

The reason their current account balances were so high was because their day-to-day spending had been running well below their modest income. Looking back on historic bank statements, I could see this had been the case for many years.

My parents-in-law’s experience illustrates what retirement researchers have found: that we actually spend less as we age, not more.

A few years ago, analysis of official data by the International Longevity Centre found that a household headed by someone aged 80 or over spends, on average, 43 per cent less than a household headed by a 50-year-old.

They found that, like my parents-in-law, many older households continue saving throughout retirement. Those aged 80 or over save an average of £5,870 a year.

This average masks the fact that a significant minority of older people struggle financially. Nonetheless absolute pensioner poverty has fallen significantly over the past 20 years as improvements to state pensions have been made.

While higher income retirees tend to save more and earlier than lower income retired households, the data suggests that the majority of people save progressively more as they move through retirement.

You might think that the costs of long-term care would undermine this theory, but apparently not. Analysis of the data shows that only about 6.5 per cent of households led by someone aged 80-plus are putting money towards care fees, suggesting that such expenditure is atypical.

This got me thinking about the implications for younger people facing competing demands on their present income to fund housing, university fee repayments and other short-term needs.

Contrary to the perception that the younger generation will never be able to save enough to fund a decent retirement, my analysis suggests that they can.

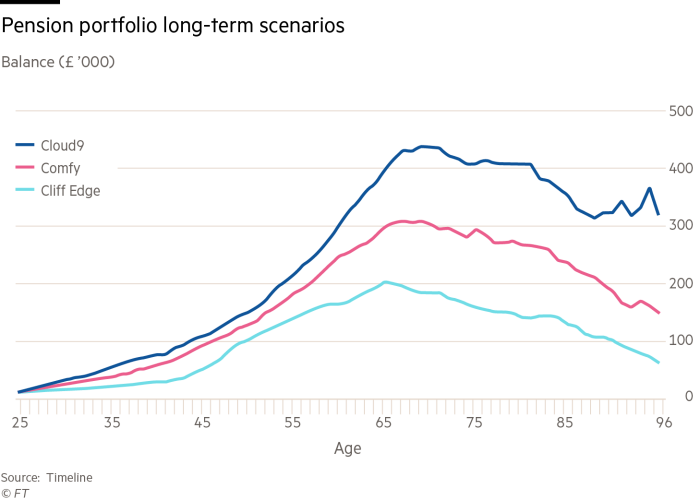

If a young person joined a workplace pension at age 25, paying the minimum 5 per cent of salary to get their employer’s contributions, and made material increases to contributions at age 41 and 51, when they are more likely to have higher real income, they could fully retire by age 71 with an annual income of £20,000 in today’s terms, as illustrated in the chart.

Not all of the assumptions in this analysis will necessarily turn out as expected. For example, I assumed investment costs will be 1.5 per cent a year, but in reality I think these will be lower in the long term, as greater transparency and commoditisation of the investment market gathers pace. All other things being equal, lower costs mean more return for the pension saver and a higher income.

Women tend to suffer more breaks in and variation of their income than men, due to childbirth and a tendency for them to have higher caring commitments, implying a lower saving capability.

FT Money event

The 100-year life

Are you financially and emotionally prepared for the possibility that you could live to the age of 100?

In the face of increased longevity, the traditional concept of retirement is becoming outdated.

Instead of planning to slow down, many of us are contemplating the prospect of working for longer, changing careers and even going back to university. Yet for those making this transition, there are also financial challenges to overcome as the pensions landscape changes.

The next FT Money Investment Forum, Are You Ready for Your 100-Year Life?, will be held on Monday June 18 in the City of London.

Chaired by Claer Barrett, FT Money editor, guest speakers at the evening event will include London Business School professors Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott, authors of The 100-Year Life: Living and working in an age of longevity, and Lindsay Cook, the FT’s Money Mentor columnist.

Tickets cost £35 including canapés and a glass of wine.

To book tickets and see full terms and conditions, visit FT.com/moneyevents

I also used the historic long-term returns for a pension portfolio invested 60 per cent in global equities and 40 per cent in global bonds. These may turn out to be lower than the worst-case (cliff edge) scenario shown in the chart. If they turn out to be the mid-range (comfy) or best-case (cloud 9) scenario, this means the individual could retire earlier or spend more.

The vital lesson for younger people is that they should not opt out of their workplace pension scheme. It’s also OK for them to pay the minimum amount necessary to qualify for their employer’s contribution. And they must adopt a sensible investment strategy and be prepared to increase their contributions when they are older.

They also need to be flexible about when they expect to retire and accept that this will probably be later than their parents did and is most likely to be a gradual process, rather than a single life event.

If you feel something is very hard or unobtainable, the chances are you’ll feel powerless and give up before you’ve started. Planning financial independence — making paid work optional, working because you want to not because you have to — is within reach of most young people, but only if they participate in their workplace pension scheme.

There are lots of ways to build wealth, including building a business, inheriting and buying property. But making modest contributions to a tax friendly workplace pension plan will for most people be the foundation upon which their long-term security is built.

My father-in-law believes money gives you choices in life. His careful spending and diligent saving throughout his life shows how, even when one’s health begins to decline, it doesn’t have to be a source of worry.

Jason Butler is an expert in financial wellbeing. He is the author of Money Moments: Simple steps to financial wellbeing Twitter: @jbthewealthman

What to put in and take out for a smooth path to retirement

Accumulation phase (all adjusted for inflation):

Age 25 to 40: Earns £25,000 a year; annual contribution to the portfolio is £2,000 (8% of salary).

Age 41 to 50: Earns £30,000 a year; annual contribution to the portfolio is £3,600 (12% of salary).

Age 51 to 65: Earns £40,000 a year; annual contribution to the portfolio is £6,000 (15% of salary).

Decumulation phase (adjusted by inflation):

Age 65 to 70: semi-retired, earning £10,000 a year and withdrawing £10,000 a year from portfolio.

Age 71 onwards: fully retired, withdrawing £12,000 a year. Also receiving £8,000 in state pension, giving an income of £20,000 or 50 per cent of pre-retired income.

The historical success rate for this investment strategy is 100 per cent.

Comments