Nick Park on why he ‘refused’ to sell Wallace and Gromit

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

You can’t fault Nick Park under trades description law. For someone working and world-famous in animation, he’s very animated. When we lunch at The Northall, a bright, big, modern-palatial restaurant at the Corinthia Hotel in London, he doesn’t stop talking. At one point — having declined a first course but insisted that I have the lobster bisque I’m eyeing on the menu — he says, “Do you mind me talking while you eat? I’ll just talk. You carry on.” Interviewer’s dream!

I almost hear his beloved Wallace in the Lancastrian accent. (“Carry on eating, Gromit. I’ll just invent something else”.) Film and television audiences have been hearing and seeing Park’s Plasticine characters ever since 1989, when A Grand Day Out introduced Wallace, an addled Lancastrian inventor in knitted sweaters, and his dog Gromit, a creature with two dementedly expressive eyes and an air, possibly justified, of intellectual superiority.

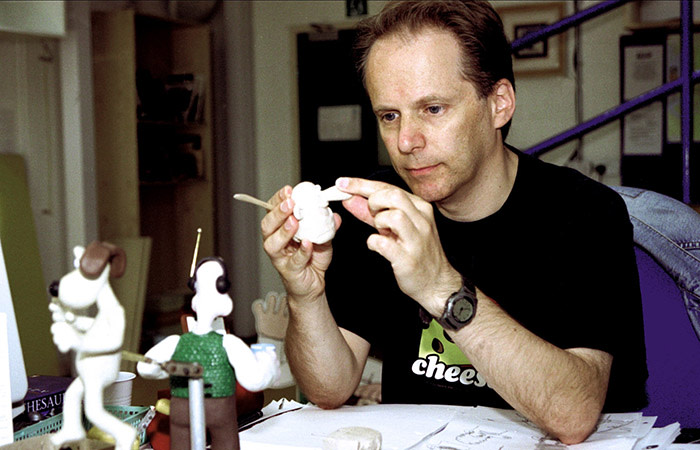

Here and in half a dozen ensuing capers, Park proved himself a British eccentric in the primitive-but-adorable mode. (Compare Heath Robinson, Rowland Emmett or Park’s beloved Beano comic artists.) Model animation using clay and frame-by-frame stop-motion techniques was “old-fashioned” almost before Park grew up. Laborious too. Models have to be changed for each successive frame to simulate motion: body position, facial expressions, gestures, mouth movements. Five seconds of completed footage per day is a blue-streak pace.

But the Wallace and Gromit shorts, followed by feature films introducing other characters, starting with Chicken Run, became an international wow. They won prizes and gained Hollywood contracts — with DreamWorks, then Sony — for Aardman Animations, the Bristol-based studio Park joined in 1985. And they unleashed an industry of tie-in products from toys, books, calendars to greetings cards, resembling a cottage version of the Star Wars bonanza.

When we meet, Park is fresh, or nearly, to the task of talking about his new animated feature Early Man . His crisp blue shirt — “I don’t usually wear these, I prefer T-shirts” — announces a director who has cleaned himself up for the global publicity push; although he claims he’s not quite there yet mentally.

“I only signed off on the film last week. I feel I’ve just come out of a ship’s engine room still covered in grease.”

A waiter takes our order. Two stems from a flower vase stick surreally up behind Park’s head, as if growing directly from it. No less surreally, when I start our lunch order by saying, “One steamed lemon sole”, the waiter says, “Between the two of you?” (I’m on the edge of saying, “We’ll do the comedy”.)

When I say I enjoyed the film, Park looks relieved. “I’m still too focused. I lack objectivity, so it’s nice to hear it’s going down all right.” As Britain’s best-known animation director and winner of four Oscars, he’s under pressure to maintain standards.

The new story introduces a Stone-Age tribe living in an isolated valley, turfed out to mingle with the invading Bronze Agers — led by a French-brogued lord. Then the tribe stages a bellicose sports contest to win the right to return to its precious verdant valley.

Park dreamt up Early Man as an idea years ago — “Prehistory was so different from where I’d been before and the studio [France’s StudioCanal] thought so too” — and blames his hero Ray Harryhausen, the late legend of Hollywood stop-motion.

“I saw One Million Years BC at age 11 [Harryhausen did the film’s special effects]. I was a massive dinosaur fan and it was like a dream come true. That’s really the film that made me pick up my parents’ home-movie camera. I made a film when I was 13 called Murphy and Bongo, a little story of a caveman and his Brontosaurus, made with Plasticine.” He pauses. “I never thought it would come to this.”

“This”, of course, is indefinable; wonderfully so. Is it having a brand of animation and a band of characters (don’t forget Shaun the sheep, Rocky the rooster, or the Oscar-winning animals of Creature Comforts) known across the planet? Or is it having the industry muscle to shrug off deals, as his company Aardman Animations has, with over-demanding Hollywood majors such as DreamWorks (Chicken Run, Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit) and Sony (The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists!) in order to forge an alliance with the artist-empathising French?

Aardman struck its deal with Studio Canal for European distribution rights to Early Man in 2017, although in the US it will be released by Lionsgate. Aardman has held on to creative control in both cases.

In America, Park and his team had become fed up with being told to cut their model-animation cloth to suit western or Midwestern tastes. “We kept being asked, how will it play to an average kid in middle America? I’ve no idea how that kid feels. I can’t guess. We dug in our heels a lot to keep our identity.” That included not selling the rights to Park’s and Aardman’s most precious characters. “They [DreamWorks] half- own the characters who were specially created for Were-Rabbit and Chicken Run. But we refused to sell Wallace and Gromit, though they wanted them.”

So I should think. It would be like Shakespeare selling the rights to Falstaff or Dickens to Scrooge. Wallace and Gromit are British national treasures and heritage. They also make no concession to life down south in England, least of all to its capital. Aardman was pressured more than once in America, Park says, to ease up on the broad vowels and burred brogue in the films’ dialogue.

The NorthallCorinthia Hotel, 10a Northumberland Ave, London, WC2N 5AE

Lobster bisque £14

Steamed lemon sole £27

Loin of venison £38

Sparkling water £5.50

Glass of house rosé £10

White wine spritzer £16

Black coffee £6

Total (inc service) £131.31

The waiter plies us with sparkling water. But with our minds somewhere between Lancashire and Los Angeles, it’s all shimmering background detail. That includes the restaurant now filling up with living illustrations of the smart-casual look. The Northall is so big and airy, with columns, recessed ceiling and floor-to-cornice windows, that no one hears anyone else talk.

Although Early Man has two or three hilarious new characters, even they, I suggest to Park, have strands of the primordial Park-world DNA. Hognob, for instance, the caveman hero’s nearly dumb but ingratiating wild-boar companion, is a Pleistocene-era Gromit, isn’t he? (Pleistocene, Plasticine; keep up with the overt or covert Aardman puns.)

“I knew he would inevitably be compared,” Park says. “But I was trying to create a new character. The ‘sidekick’ is very key to our work really. Gromit would be rather put out if you treated him as a pet, whereas Hognob is much more a pet, like a lively, keen puppy.”

Hognob has a glorious scene giving Bronze Age leader Lord Nooth a back-and-shoulders massage when Nooth, taking a bath, mistakes the porcine interloper’s footfall for his body-servant’s. It’s the Tony Curtis/Laurence Olivier scene in Spartacus gone gaga. Tom Hiddleston, voicing Nooth, makes “Ooh-aah” noises of sensual appreciation as Hognob pummels his shoulders.

Park recalls he did the pummelling himself, in the dubbing studio, at Hiddleston’s realism-seeking request. It was another moment of “I never thought it would come to this” — “Me giving Tom Hiddleston a massage!” — for the man born to a family of modest means in Preston, Lancashire, in December 1958.

His mother was a dressmaker (“She still is really. She’s a spry 88”) and his father was a photographer. He was also — didn’t I read somewhere? — an amateur inventor. “ ‘Inventor’ might be too strong a word,” Park says. “He was always in the shed. ‘Oh, I’ll make a shelf’. ‘Oh, I need a stool, I’ll go and make one.’ ”

Park’s father sounds like the inspiration for his own most famous inventor character. Yet the director didn’t realise the dad-and-Wallace connection until after making his first film featuring the suburban boffin and weird dog. That was A Grand Day Out (1989), his graduate movie project for the National Film and Television School.

“He loved being compared to Wallace. I hadn’t realised the similarity till that film. It was after Wallace had built the rocket to the Moon in his living room that I thought, ‘I’ve made a film about my dad!’ ”

My bowl of soup, although tasty, is rather tepid. When it is cleared away, we get two main courses and they look piping hot. Park has lemon sole with broccoli and smoked garlic-and-parsley butter. “I want something light,” he says. “Otherwise I’ll fall asleep this afternoon.” For the same reason, he adds: “I’ll have a white wine spritzer”. I’ve chosen venison with braised red cabbage, salsify and peppered sauce. First taste, delicious. Plus a glass of house rosé.

Park’s dad was instrumental, he goes on to say, in creating Nick Park the film-maker: something that was at that time, in the provincial world of Preston, Lancashire, unimaginable.

“You never heard of anyone going into TV or films. It wasn’t an option. But my dad was a photographer by profession. He worked for a firm of architects. Someone at work had made a corporate video which had some animation. I think, some cut-out sheep moving on a hill. He handed me the home-movie camera and said, ‘Have a go, here’s this button’. That really inspired me. I still had to find out everything from the library. There was nothing on it at school. But there actually was a button on that camera that said, ‘Animation’.”

Park went to Sheffield Polytechnic, now Sheffield Hallam University, to study art. “I was always sketching, doodling. I came up with this guy called Mr Norris originally, who had a magic bike that could fly. And he kept a cat in the basket. That was Gromit before he became a dog. Later, at the National Film and Television School” — a quantum move to Beaconsfield, near London — “I got these sketches out and thought, what if he built a rocket? And so he became Wallace.”

I’ve read how Gromit got his name: Park has an electrician brother who kept using the word “grommets” in the family’s hearing; as in rings or washers. But where did “Wallace” come from?

Funnily enough it came from a dog. “A large old lady one day got on the bus into Preston. She had this large black Labrador and she said (broad Lancastrian accent), ‘Come on, Wallace!’ ‘Sit down, Wallace!’ ‘Behave, Wallace!’ I just loved the name.”

Two later Wallace and Gromit films went on to win Best Animated Short Academy Awards: The Wrong Trousers (1994) and A Close Shave (1996). Before that Park’s debut Oscar was for Creature Comforts, a brilliant compendium of mini-sketches, in which “real” audio interviews with ordinary folk were set to the synchronised mouth movements of Park animals. His and Aardman’s fourth and last Oscar (to date) was for Best Animated Feature: won by 2005’s The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, a country-house horror comedy made for DreamWorks after the success of Chicken Run.

Aardman was less successful in the US after that. But Park himself was barely involved in its computer-animation feature debut Flushed Away (2006), nor in two 3D collaborations with Sony, Arthur Christmas (2011) and The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists! (2012).

The team returned to its roots and things look better already. Before Early Man, Wallace and Gromit were successfully revived for the BBC with A Matter of Loaf and Death, a spoof murder mystery.

Will he ever get fed up with that barmy duo? “No, I love them. I’m so at home with them. I have more ideas. With Peter Sallis passing away last year [the actor whose lugubrious-comical tones endowed Wallace], it’s more difficult. He was quite special, wasn’t he? But Peter didn’t want to do everything. He didn’t do the voice for video games or sat navs, for instance. So we have an understudy and he’s very good.”

Early Man makes a bid to bind past to present by insisting that a football culture, no less, existed in the Stone Age. A soccer match forms the film’s extended climax. Why not? Anarchic primitivism shading into zany anachronism — that’s what we want and expect from a Nick Park film, isn’t it?

Park was brought up, after all, on the Beano comic (just like me), a bastion of 1950s/1960s British folk culture. He practically purrs when I mention this weekly nonsense-sheet now nearly legendary. “The Beano. That was my world, my window on reality. Dennis the Menace, the Bash Street Kids . . . ”

Yes, I say. “And teeth”, I add. Those Beano characters, like so many Park characters (except of course the mouthless Gromit), had such maniacal teeth. That’s so British, isn’t it? Look what Hollywood did when it wanted to create a funny British secret agent. Austin Powers. Gave him terrible teeth.

Park laughs. “It is a British thing.”

(He mentions too Sallis’s early sallies as the voice of Wallace. Uttering the word “cheese” with proper Lancashire lengthening — “More chee-eese, Gromit” — stretched the Plasticine mouth so much that it showed all his lower teeth. “Let’s push it, I said. It’s funnier.”)

We are asked if we want to order anything else, but the dessert menu makes you feel full just by reading it — banana sticky toffee pudding, Eton mess with green tea meringue — and we settle for one black coffee. Just for me, I say, before the waiter has another chance at “Between the two of you?”

I’ve got one last question — and it’s a biggish one. Brexit.

Don’t we just know, in this time of national obsession about the ripping of the near-umbilical cord with Europe, that people will seize on the plot of Early Man as a Brexit allegory?

Park gives a silent, friendly groan. I didn’t know people could groan with their faces, but he’s an animator; he knows how. “We became aware of that. But we didn’t want the film to be perceived as a political statement. Because we’d started filming it before the Brexit referendum and we never saw it as an allegory of that.

“But we were suddenly aware of what we had in our story. I didn’t want us to be seen as anti-European. I didn’t want the film to be adopted by Leave campaigners. I tend to be on the Remain side. The Europeans — if you see the Bronze Age characters as that — aren’t actually bad in the film. We get to love them and football brings everyone together. Nooth isn’t a villain. He’s just an avaricious individual who happens to be French.”

The call of prehistory soon scatters thoughts of modern history. It’s back to work for Park, who takes a gracious, smiling leave. The flowers have stopped sticking out of his head, in that surreal perspective I had on my guest across the table, and he’s back to being the ordinary, nice bloke from Lancashire. The one who became internationally famous by putting the “potty” into putty.

Nigel Andrews is the FT’s film critic

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments