Covax falters as rich countries buy up Covid vaccines

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

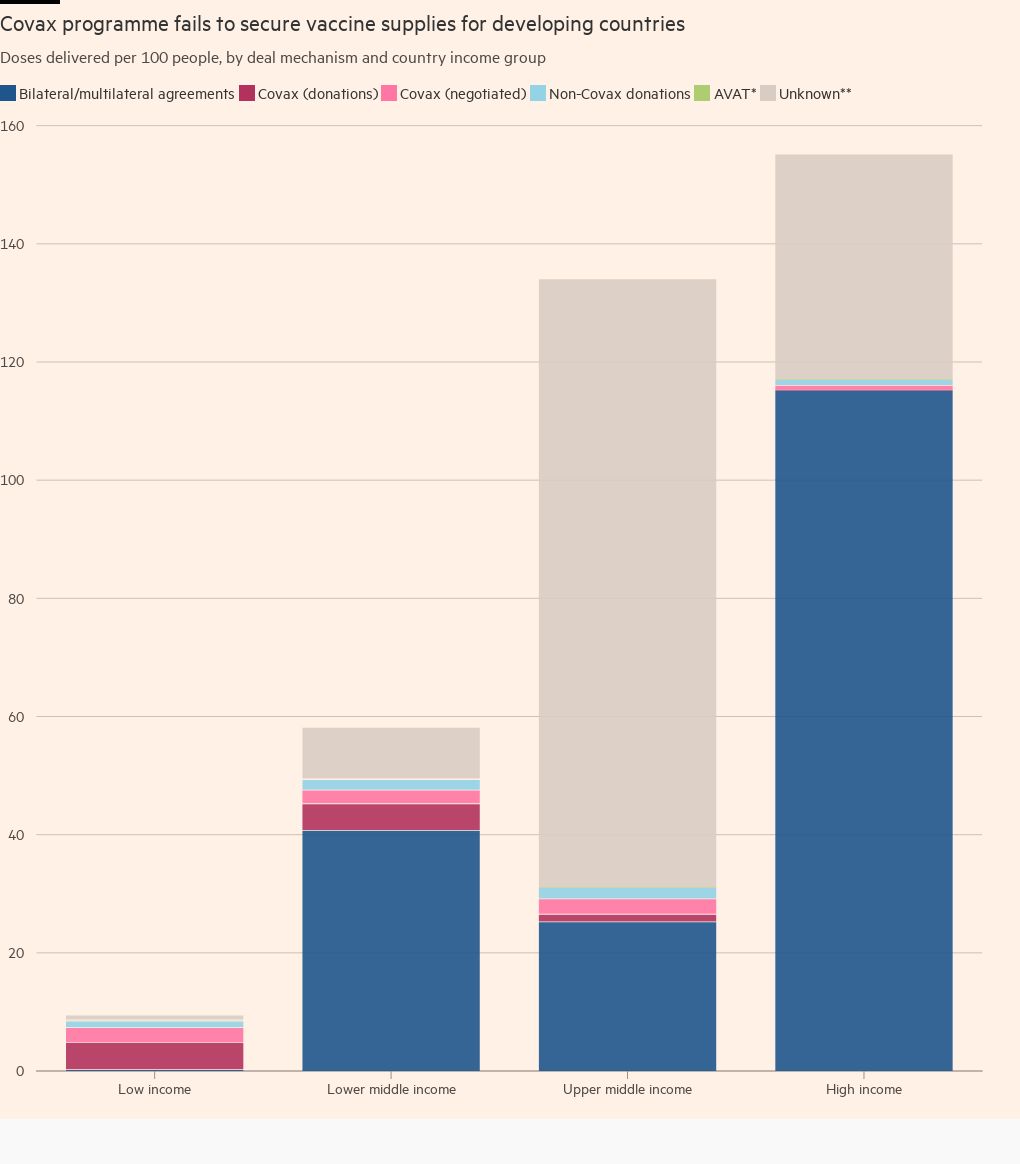

Wealthy countries have received over 16 times more Covid-19 vaccines per person than poorer nations that rely on the Covax programme backed by the World Health Organization, according to analysis by the Financial Times.

Just 9.3 vaccines have been delivered to low-income countries for every 100 people, the data show — 7.1 of which have been through Covax. This compares with 155 for high-income countries, of which 115 were received through known bilateral and multilateral agreements, according to data compiled by Unicef.

The data underline how Covax, a procurement scheme set up last year to give people in poor countries equitable access to vaccines, has largely failed so far. The consequences are far-reaching, as insufficient inoculation in poorer regions could lead to a rise in cases and the emergence of more virulent strains, and hold back the global economic recovery.

As the west prepares for winter, the gap between haves and have-nots remains wide. Less than 3 per cent of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose, according to Our World in Data, compared with three quarters in richer nations.

“You’ve really got to look hard at the model,” said Kate Elder, a senior vaccines policy adviser at the Médecins Sans Frontières access campaign in New York. “We need structural change if we’re going to avoid repeating this disaster in the future.”

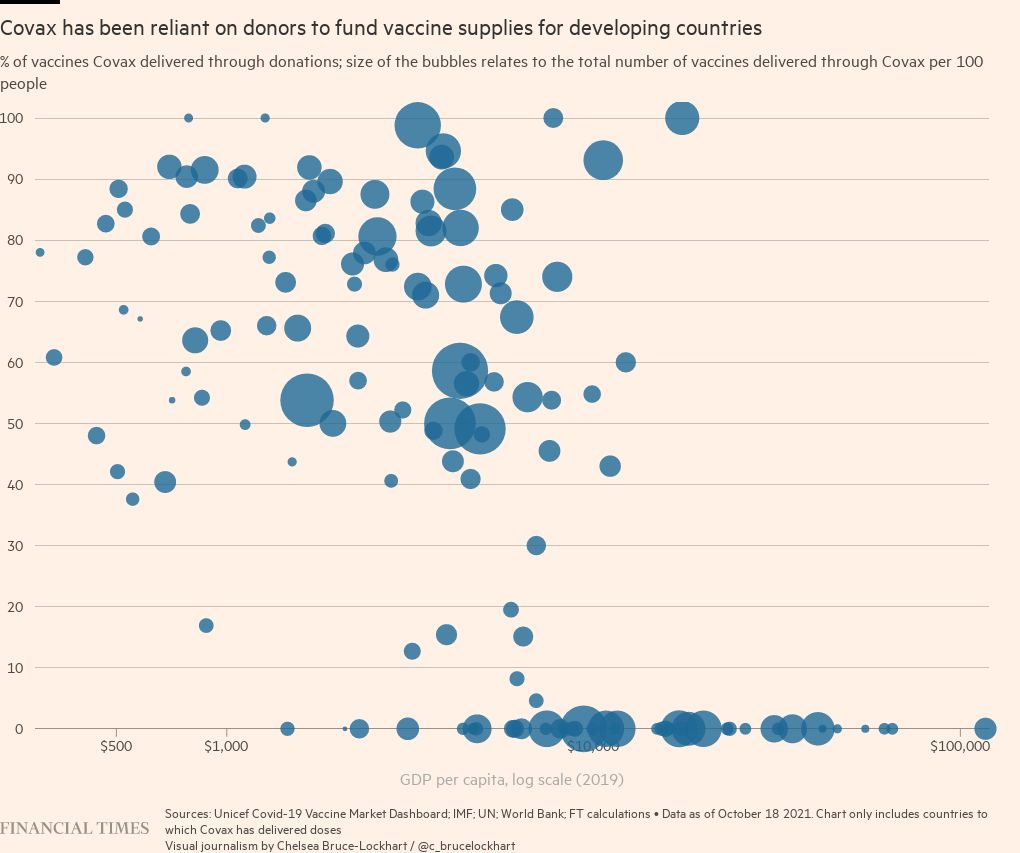

In bypassing the WHO-backed scheme in the race to buy vaccine supplies from manufacturers, wealthier economies that are rolling out booster shots have prevented millions of the world’s poorest people getting their first jab, forcing Covax to rely heavily on donations.

The scheme has only delivered about 400m doses out of an already-cut yearly projection of 1.4bn. And, after slashing its supply forecasts last month, it faces the challenge of delivering about 1bn doses in 68 days — almost 14m doses a day — to meet its 2021 goals.

Collective hope

Covax was supposed to ease procurement of vaccines for poorer nations by using collective bargaining power to widen access as much as possible. But it faced delays in shipments — when they arrived at all.

As richer countries struck their own vaccine contracts with manufacturers, poorer countries sought to do the same.

Striking separate vaccine deals weakened the facility’s overall negotiating power because Covax was left to negotiate on behalf of fewer nations.

Another failing, said one high-ranking official with direct knowledge of the issue, was that Covax had “no power at all” to coerce manufacturers to honour their contracts through, for example, lawsuits.

‘Left behind’

“Covax is definitely being left behind, [the] industry is prioritising other bilateral contracts,” the official said.

The International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations, a lobby group, insisted there was “no ‘prioritisation’”. “Manufacturers are just fulfilling their contracts; whether they are with governments or Covax,” it said.

To boost the availability of vaccines, the WHO earlier this month issued a renewed call for dose-swapping and called for a global moratorium on booster shots until the end of the year.

“Our priority now is to work with manufacturers, donating countries and . . . participants to ensure conditions are in place for effective delivery at scale during this period and beyond,” said Gavi, a vaccine alliance with the goal of increasing access to immunisation that set up Covax alongside the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness.

But people with direct knowledge of Covax’s procurement system say an underlying lack of vaccines and leverage will persist in the coming months.

African Union officials forecast that Covax will deliver about 470m doses to African countries by the end of the year — less than a quarter of what would be needed for its entire 1.3bn population on two-shot regimens.

The impact of Covax’s problems were made worse earlier this year when India’s Serum Institute, which makes the bulk of the Oxford/AstraZeneca shot for the developing world, was ordered by the Indian government to halt exports in order to fully immunise the country’s population amid a surge in cases.

An additional 600m Oxford/AstraZeneca dose deal, struck between New Delhi and the Serum Institute last month, has left officials at Covax, the university and the company concerned that projections will have to be further cut, although the vaccine manufacturer has said exports could resume as early as this month.

“If they do not restart that’s further going to hit the availability of vaccines for other countries,” said Bruce Aylward, a senior adviser to the director-general of the WHO, noting, however, that there would be “other options” such as using vaccines made by other manufacturers. “It depends on when they want to serve those contracts.”

The Serum Institute, Oxford university and AstraZeneca declined to comment. Gavi said the easing of export restrictions would add to its projected supply.

Covax recipient countries continue to only have month-by-month visibility into deliveries, which makes planning difficult, officials said.

“We managed to solve the supply of vaccines, thanks to some important donations, but the current proportion is 60 per cent public investment in vaccines and 40 per cent donations,” said a senior Angolan official, in the country’s capital, Luanda.

“At the beginning of the pandemic we thought that the world had changed, and . . . there would be more solidarity,” the official said. “But, well, the rest is history.”

Additional reporting by Amy Kazmin in New Delhi, Katrina Manson in Washington DC and Hannah Kuchler in London

Comments