Is Europe winning the gas war with Russia?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Is Europe suddenly winning the gas war with Russia?

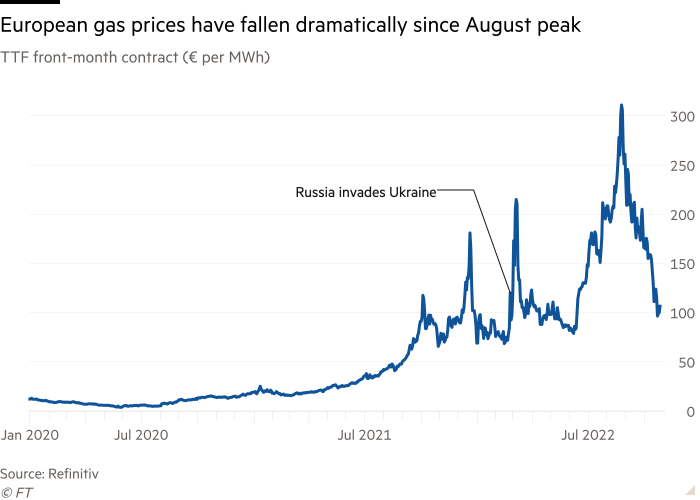

Prices have dropped by almost 65 per cent since hitting an all-time peak in August. Storage caverns across the continent are filled to bursting point ready to supply homes and industry this winter. Even seaborne liquefied natural gas tankers, which desperate buyers had to fight to pry away from Asia, are now so plentiful there are traffic jams forming outside European terminals as they wait to unload.

After months of fearing a winter beset by shortages and misery caused by Russia’s weaponisation of gas supplies, most traders will cautiously concede that Europe’s fortunes have improved. Warmer-than-normal weather in the past few weeks has delayed the start of heating season, leaving a bigger buffer of gas for the winter months, while European businesses have cut consumption sharply.

But a heavy note of caution still hangs in the air. Daring to believe that the energy crisis has somehow been resolved is dangerous given the scale of the remaining challenge.

Prices remain eye-wateringly high, particularly for early next year, and when the cold weather finally hits there remain concerns Europe could quickly burn through its gas reserves, potentially still leading to extreme tightness in supplies after Christmas. Gas at around €115 per megawatt hour is still equivalent to almost $180 a barrel in oil terms. Contracts in December and January are above $230 a barrel equivalent.

“The picture in Europe is that people are a bit complacent — prices have dropped this week, storage is full, but it is too early to say it is going to be fine,” said Alex Tuckett, Head of Economics at CRU Group, a commodities consultancy. “You don’t know how cold the winter will be, we are not in the heating season. The big variable is the weather.”

Others are slightly more optimistic. Henning Gloystein at Eurasia Group argues that Europe can afford to be a little more confident having successfully filled its storage facilities — enough to meet about two months of gas demand — over the summer, though at a painfully high price.

“Full storage tanks make severe winter energy rationing or even blackouts less likely, potentially lessening — though not preventing — an expected recession,” Gloystein said.

But weather’s dominance over the gas market means he’s not quite prepared to say the worst is definitely over. If the winter is mild, then Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, could end the season with its storage facilities almost half full.

But if it is just slightly colder than normal, then “German gas inventories would be virtually depleted by end-March, possibly requiring late winter rationing or supply cuts”, Gloystein said.

That leads to one of the biggest fears in the industry: even if Europe can scrape through this winter, next year might be worse. Spring will bring some reprieve from the immediate crisis. But the gas market does not stop. When heating demand drops off, the race to refill storage starts all over again.

But unlike the first six months of 2022, when Russian supplies were still largely flowing into Europe despite Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, the assumption has to be that this time flows will be close to zero. So the continent will face an uphill battle to start winter in 2023/24 in as strong a position as it is today.

Europe has already tapped almost every available source of gas, from increased LNG imports to asking Norway to maximise production for months. There’s little in the way of supply additions expected globally until the middle of this decade. The EU will boost its ability to import LNG through floating terminals in Germany and the Netherlands but they’ll be competing for the same limited pool of supply. And without Russian gas, the EU will need even more LNG over the next 12 months.

So the current relatively low (ish) price for gas might be as good as it gets for a while. The futures market is already reflecting these concerns, with contracts trading above $200 a barrel equivalent even for the first quarter of 2024.

Lower prices might still materialise. Energy executives in Europe think the full extent of demand destruction is yet to be seen, as some companies have still been shielded by long-term contracts supplying them with gas at prices well below market rates.

As the contracts roll off in the coming months we should expect more businesses vulnerable to energy price shocks to fold. It’s the market’s classic way of lowering demand. But don’t expect those who lose their incomes to cheer that gas might get a bit cheaper as a result.

If France can sort out its maintenance-racked nuclear fleet there might be a more positive reprieve, as less gas will need to be burnt for electricity across the continent. But the most likely outcome remains that governments are going to still be on the hook for significant support to households over the next 18 months. Tightening of middle class household budgets also is likely to add to economic pressures.

So is Europe winning? Long-term, it is demonstrating that market economies can find a way through. But sadly there’s a lot of pain to come.

Comments