Policing in the US: ‘If coronavirus doesn’t kill us, the cops will’ | Free to read

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Three years ago, Donald Trump stood before a group of white-gloved — and mostly white — police officers on Long Island, and offered a bit of professional advice.

“Please don’t be too nice!” the self-described law-and-order president implored, as the officers whooped in delight.

After the police killing of George Floyd, a black man, in Minneapolis unleashed America’s worst civil unrest in half a century, Mr Trump this week showed no sign of reconsidering his attitude to policing. Governors should “dominate” protesters, the president declared, as he agitated to send the military on to America’s streets.

The extraordinary public outcry over Floyd’s death on May 25 indicates that many Americans feel otherwise and want changes in how a politically polarised and racially vexed nation is policed. Some are demanding incremental reforms, such as banning chokeholds during arrests, and creating databases to better track police violence. Others want wholesale changes, such as weakening police unions that protect officers, starving police departments of resources and rethinking their role in a democratic society.

“If coronavirus doesn’t kill us, the cops will,” Diana Richardson, a member of New York State Assembly, told protesters on Thursday at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn. “We all know that NYPD is out of control. And we know there has to be a major overhaul in the police department.”

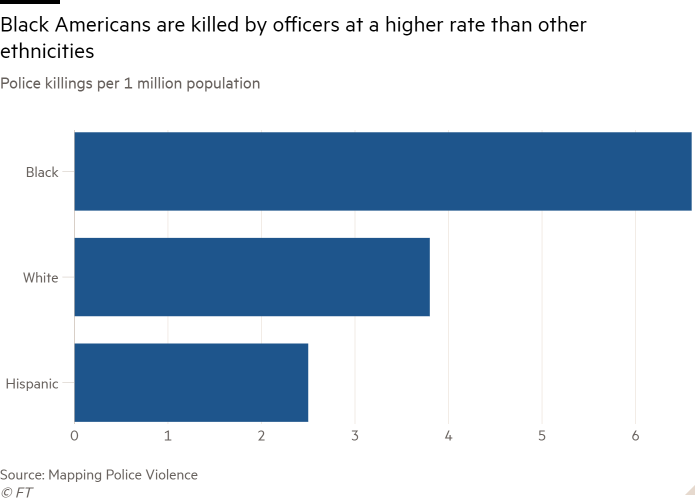

Darrick Hamilton, an Ohio State University professor who specialises in race and ethnicity, says that while there is also police violence directed at whites, the greater frequency in which it occurs to black people “is rooted in a society that creates a hierarchy based on skin colour”.

According to Alex Vitale, a Brooklyn College sociologist and author of The End of Policing: “These police departments have become incredibly politically powerful. Both the departments themselves and the unions that represent the rank-and-file officers.”

‘Nothing about this is new’

A jumble of disparate images from around the country attested this week to the complex relationship between America’s police and public. There were officers walking past the limp, bleeding body of an elderly man they had shoved to the pavement, but also officers laying down their batons and kneeling in solidarity. There were seas of peaceful marchers on summery afternoons, but also violent mobs looting at night, and in one case, bashing a fallen police officer over the head with a board.

But the dominant image remained that of Floyd, arrested on suspicion of passing a counterfeit $20 bill, sprawled on the road and gasping for breath for eight minutes and 46 seconds while a white officer, Derek Chauvin, pressed a knee into his neck. “I can’t breathe,” Floyd pleaded at one point, while Mr Chauvin, since accused of second and third-degree murder, wore an expression of nonchalance. The fact that the murder was recorded by a police camera in broad daylight was another reminder that the recent adoption of such devices is no guarantee against abuse.

Six years earlier, Eric Garner uttered “I can’t breathe” in Staten Island, New York, as he died of a fatal asthma attack brought on by a police chokehold. Garner had been detained on suspicion of illegally selling cigarettes. Less than a month later, Michael Brown, a black teenager, was shot dead in Ferguson, Missouri, by a white officer, triggering a summer of unrest.

“These issues have been going on for as long as our country has existed, and even longer,” says Kelly Welch, a criminologist at Villanova University. “Nothing about this is new.”

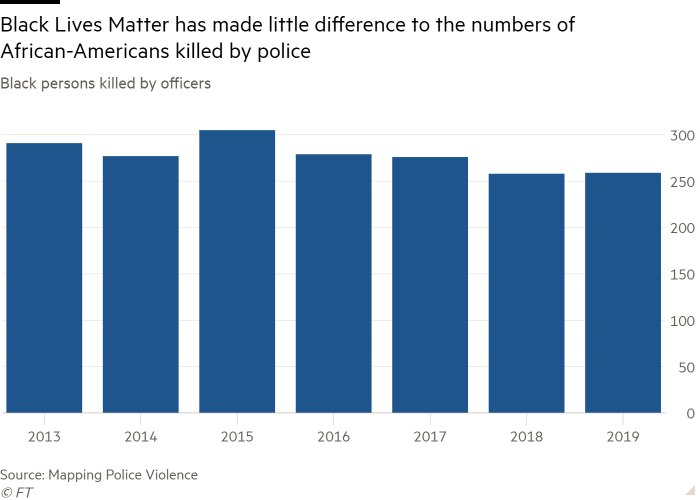

Even after Ferguson and the nationwide debate on policing that it provoked, police killings remained steady at about 100 a month, according to Campaign Zero, a group that aims to use data to reduce police violence. “We think about the pantheon of issues in this civil rights space that have been addressed — the police is one of the only issues that hasn’t really changed,” DeRay Mckesson, who founded Campaign Zero after Brown’s death, told Yahoo News this week.

If you take the long view, as Paul Chevigny does, the situation has improved. Mr Chevigny, a writer and law professor at New York University, has been chronicling police violence since the 1960s — a time when there were no body cameras and few limits on the use of lethal force.

“The number of instances in which people are killed by the police has dropped a lot in America in the last 50 years, but [each case] is now much more notable,” says Mr Chevigny, citing media coverage and the impact of social media.

For all the outrage over Floyd’s death, he was not at all convinced it would lead to reform. “The public blows hot and cold on this,” says Mr Chevigny, noting that the violence that has marred some protests might prompt many to side with Mr Trump. “It’s not yet clear how this is going to play out.”

New York’s testing ground

To an extraordinary degree, much of America’s debate about policing has played out in New York City, and William Bratton — a Bostonian, with the accent to prove it — has been at the centre of the debate.

Mr Bratton took over as police commissioner in 1994, under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, pledging to “take back the city block by block” and believing the force had become overly cautious and bureaucratic. Mr Bratton used statistics to determine where crime was happening and a “broken windows” policing approach in which officers pursued even the smallest offences to prevent bigger ones.

The strategy seemed effective: murders in New York fell from 2,245 in 1990 to 318 last year. Along the way, a city gripped by fear came to relish its standing as “the safest big city in America”. Mr Bratton went on to Los Angeles, to repair a force disgraced by the 1991 police assault of Rodney King, a black motorist. Then prime minister David Cameron sought his advice on tackling the UK’s gang culture.

“I think what’s taking police by surprise is how much anti-police sentiment there is in the country despite police over the last 25 years reducing the crime rate,” Mr Bratton told the FT this week.

Police methods should be ever-evolving, Mr Bratton argues, and officers must be retrained throughout their careers. He was surprised to learn that in Minneapolis officers were still using chokeholds, which has been banned in a number of cites.

Still, he appeared stung by some of the criticism of excessive policing in the 1990s and allegations of over-incarceration that have accompanied this week’s demonstrations. “Was some of that occurring? It certainly was, as we look back . . . But how do you not argue for more policing when crime had been going up for 25 straight years?”

How can one oppose more policing in a place like Chicago, he adds, which recorded 85 shootings last weekend, including 15 homicides on Sunday alone?

The question increasingly being asked by reformers is what type of policing. The broken windows approach, say a growing legion of detractors, involved making arrests at the cost of inflaming community relations. It also became racist, they say.

“Research shows crime is happening everywhere. But if the police are only investigating it in poor communities of colour, that’s where they’ll find it,” says Prof Welch.

According to the Sentencing Project, a group that works for criminal justice reform, blacks comprised approximately 13 per cent of drug users in the US from 1995 to 2005 but accounted for 36 per cent of drug arrests and 46 per cent of those convicted of drug offences.

In New York, activist policing found its ultimate expression in the intrusive “stop-and-frisk” policy that was ramped up by Mr Giuliani’s successor, Michael Bloomberg, in which young black and Hispanic men were disproportionately detained and searched by police in an effort to remove guns and other weapons from the street. In 2011, for example, New York officers conducted more than 685,000 of these searches. (Mr Bloomberg, a data obsessive, insisted on the policy’s effectiveness until his recent run for the Democratic nomination for the presidency led him to apologise for it.)

Elsewhere, police have antagonised communities by using surplus military kit sold to them by the Pentagon. Some of it was on display in Ferguson in 2014, when heavily-armed police sent to control crowds looked as though they were Marines heading to Falluja, Iraq. President Barack Obama was so disturbed by those images that he restricted the Pentagon programme — only for Mr Trump to restore it in 2017. “When you want to take our used military equipment, you can do it,” he told the officers in Long Island.

Many US police forces are now embracing more progressive approaches, including New York City, where Bill de Blasio made opposition to “stop-and-frisk” a centrepiece of his successful mayoral campaign in 2013. To the surprise of many, he then brought back Mr Bratton for two years. The mayor’s plan is for police to better understand the neighbourhoods they are serving, so they might distinguish, for example, between crimes that cause harm to residents and those that do not.

Building trust takes time, and it may be difficult when some departments are trying to introduce new, softer methods while still using the old standbys. It is also not clear in New York that the rank-and-file have bought into Mr de Blasio’s vision. Hundreds of officers turned their backs on the mayor in 2017 when he spoke at the funeral of a slain colleague. A retired law enforcement official this week accused Mr de Blasio of “putting [the police] in an impossible position” by declaring a curfew and then failing to give officers the backing to enforce it.

Punishing police misconduct

Short of reinventing policing, many observers argue the immediate priority should be to impose greater accountability. Given the ingrained nature of America’s racism — and the sometimes subtle ways it can play out — some experts believe it is better to have clear rules in place so that police understand they will be punished for misconduct. “Some people need to go to jail,” says Prof Hamilton.

Even that may be unlikely. Police unions have amassed such power that it is difficult to discipline officers — let alone dismiss them. Prosecutors tend to shy away from pursuing charges against police. Civilian review boards, implemented as another layer of oversight, are often toothless, say critics. Just obtaining data and disciplinary records has been a chore for groups such as Campaign Zero.

In New York, it took five years — and much public pressure — before the commissioner fired Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who caused Eric Garner’s death. A Staten Island grand jury had previously declined to indict Mr Pantaleo.

In Minneapolis, Mr Chauvin is likely now to stand trial. Before Floyd’s death, the officer was named in 17 misconduct complaints during his career, for which he received only two letters of reprimand. An analysis by Reuters showed that the Minneapolis force has fired only five officers in the past eight years, in spite of receiving nearly 3,000 public complaints.

“It’s unfathomable that these kinds of situations keep happening,” says Prof Welch. “But without any substantive change, we shouldn’t be surprised that they keep happening.”

Comments