High quality equities remain the best option for growth

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

With world stock markets yet again touching all-time highs and investor nerves jangling in the run-up to the US election, I have been thinking about Gregor MacGregor — perhaps the biggest swindler in economic history.

MacGregor was a Scottish adventurer who spent nearly a decade fighting in Bolivar’s army in the Venezuelan War of Independence. On his return to Edinburgh in 1820 he claimed he had been given a country in Central America called Poyais, a paradise whose capital was endowed with a majestic parliament, an opera house and generous boulevards. He began selling land.

Poyais was in reality nothing but swampy jungle. Yet, even as the first party of eager settlers embarked to sail there, the self-styled “Cazique” stood on the docks and cheerfully sold them fraudulent Poyais currency to spend on arrival.

When his deception was uncovered in Scotland he moved to London and then Paris, repeating it. So outrageous was the scam, so attractive and seemingly assured the promised returns, that people did not believe he could be lying, even when told.

I was reminded of MacGregor during an entertaining online talk this month by Mid Wynd International Investment Trust director Russell Napier. Professor Napier is the curator of Edinburgh’s Library of Mistakes, a collection of more than 3,000 books cataloguing the financial folly of humankind.

Prof Napier warned that embezzlement rises in an era of low returns — “and there’s a large bezzle out there at the moment”.

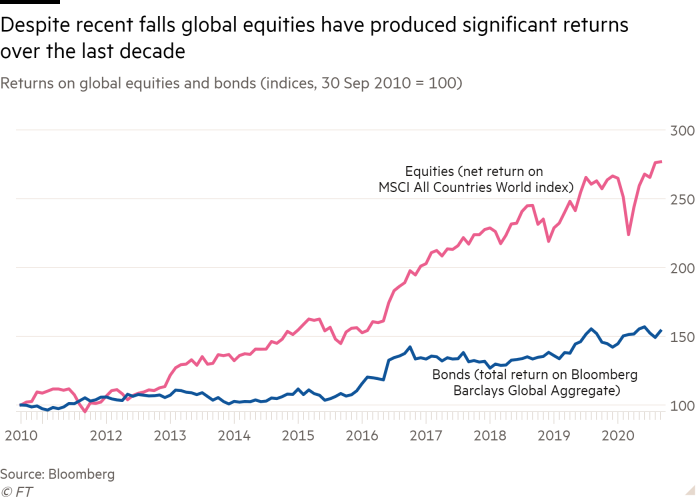

Despite the March tumble, we have enjoyed a decade of high total returns from global equities and bonds. Both are now priced at close to all-time highs. Most commentators expect investment returns to be lower in the decade ahead. And we could also be on the brink of a new era of inflation. That makes people vulnerable to false promises.

As a global equity manager, I am inevitably going to be accused of selling my industry’s wares. But I do believe equities still represent the best home for many savings.

Loss aversion means many investors are wary — it is human instinct to be edgy about investing in an asset class that saw a 34 per cent peak-to-trough crash only a few months ago. And, in the absence of a vaccine, the pandemic still poses a threat to the global economy.

We have seen extraordinary bifurcation within markets this year — Covid winners driving recovery and serious losers acting as a drag. That is not an argument for avoiding equities — it is an argument for being selective.

Good-quality companies have survived wars, not just pandemics. They share some key characteristics:

They make a product or service with steady-to-growing future demand

They make good cash profits — more than covering rent, wages, tax and other costs

Their historic dividend paying has not left them too short of cash to invest for the future

Many companies meet these criteria, but whole sectors fall down on parts. For instance, oil and tobacco fail on the future demand point.

Accept that you will not get all your calls right, so diversify between sectors — and geographically, too. The impact of the virus will be different from country to country, as will the responses of governments and the stimulus effects of growth versus inflation.

Even a modest rise in inflation may bring back bad memories in the UK, but relief in Japan where it could be helpful to the new era under prime minister Yoshihide Suga. Japanese stocks are generally modestly valued compared with those in many other markets. Japanese companies sell into the recovering Asian markets and the Chinese economy, which is being supported by Beijing.

Our funds have an investment in Sumitomo Corporation which, through its interests in a range of businesses from copper mining to construction should benefit from any economic recovery. The shares trade on 70 per cent of book value and seem able to pay a yield of 5.5 per cent this year. Furthermore, evidence of a second virus wave seems absent so far across Asia and there have been no further lockdown measures.

Some will question timing. They will say that, because the market globally is close to an all-time high, it is better to wait for a correction. They may have a point. But the problem is that while you are sitting in cash, earning close to nothing, your money is being eroded by inflation. And when is the right time to invest? Few of us get the call right — which is why we say equity investing is for pots of money you do not need for seven to 10 years.

You can drip-feed your money in, though this approach is not without flaws. In the past 30 years the UK stock market has had nearly twice as many up months as down months, so you risk paying more than needed, but this is the price of insuring against the regret of diving in with all your money at the top of a market.

Some will point to Prof Napier’s bezzle risk. The recent Wirecard debacle, as revealed in the Financial Times, shows that the bezzle is indeed large and can strike equity markets, too. Companies that seem very profitable will always interest stockpickers like us, so I am indebted to my colleague, Rosanna Burcheri, who identified through dogged analysis that Wirecard produced little cash profit, despite declaring large amounts of earnings. Similar analysis saved diligent managers from investing in Enron 20 years ago — it had accounting earnings but no cash earnings.

Fundamental analysis is the only way to spot the bezzle. Of course, there were active managers who still owned Wirecard in spite of these signals, but all European tracker funds had to hold it by virtue of its place in the Dax 30 index. At its peak in August 2018 the company was valued at €24bn on the Dax — so representing maybe 2 per cent of the index at the time.

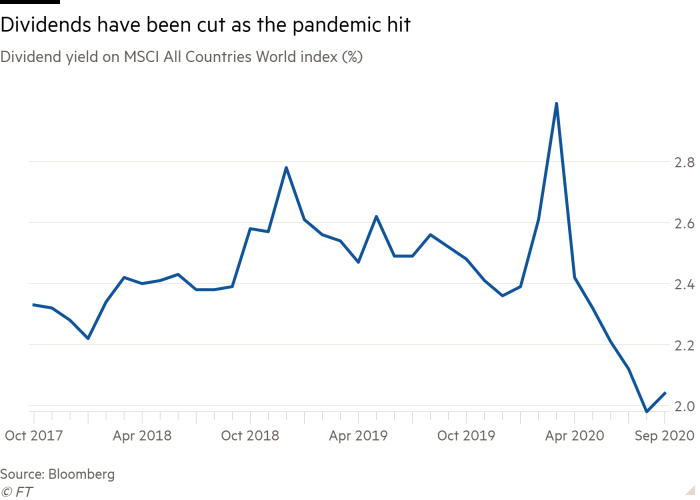

Finally, some will look at dividend cuts this year and argue that likely returns from equities just do not justify the risks. Based on past experience, we expect our funds to generate on average 8 per cent a year. An annual 7 per cent real return doubles the purchasing power of savings in just over a decade, which should be good enough for anyone. Naturally, past performance is a guide, not a guarantee. Given the potential problems, 4-5 per cent over the next decade would still be acceptable — especially when compared with what other asset classes are currently offering.

We must accept that it may take a bit longer to grow money through equities and that it will not be a smooth journey. But it will be a lot better than the journey MacGregor’s gullible victims took. Only one in three of those who sailed to Poyais survived, with the rest succumbing to malaria and yellow fever. Don’t fall for those alluring scams. And don’t be put off owning quality shares.

Simon Edelsten is co-manager of the Mid Wynd International Investment Trust and Artemis Global Select Fund

Comments