Tom Dixon: my social-distancing survival guide

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“It’s not that I enjoy chaos, but I do find this moment interesting from a perspective that I like change – that motivates me quite a lot,” says 61-year-old industrial designer Tom Dixon, pondering his personal experience of the coronavirus crisis. “For a designer there are lots of problems or situations emerging now that need to be rethought.”

Dixon, who founded his eponymous brand in 2002 as the aftershocks of 9/11 reverberated around the world, is intent on turning a negative into a positive. Despite being at the coalface of commerce as it is brought to its knees by the global pandemic, he is taking positive action by collating a “self-distancing manual” – a compilation of creative concepts, which he plans to publish when complete, exploring “how to take back control and prepare for a relaxation of constraints”.

He pulls no punches when asked how the crisis has impacted his businesses. “It’s been an abject disaster, given that we’ve got the restaurant, 200 people and offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai and New York,” he says, likening the experience to watching a slow-motion car crash. “We had early warning signs but were powerless to intervene.”

Dixon, like countless others, has had to face hard economic decisions during the crisis. The business has let people go and he has implemented a three-day working week. “Of course, the vagueness of the government’s response is very difficult, even though they themselves are dealing with unknowns,” he says. “It makes it impossible to plan with precision. We can kind of second-guess how things will go from what is happening in China. But the world we emerge into is really the big question mark.”

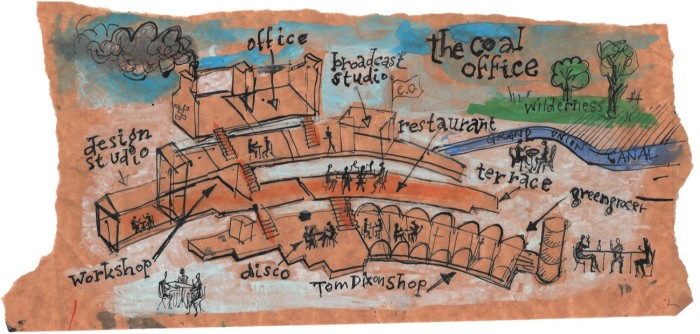

In response to this question mark, his headquarters at London’s Coal Drops Yard in King’s Cross is being transformed into something of a social-distancing lab. Some of the ideas he is testing here have been in his mind for some time, while others explore quandaries posed by the new world order. “It’s an expensive building and I’ve been thinking for a long time how to maximise the space. Forget Covid – having a furniture showroom in central London is a disaster. When did you last buy a table?” he jokes. “So when we came to King’s Cross in 2018, my obsession was to create a place where design, food and work interact seamlessly.”

Dixon was left with an empty 17,000sq ft building during lockdown, so these ideas crystallised rapidly. Early on, his restaurant was turned into a “fresh food hub”. “Then it struck me, as I was travelling to work on an empty train, that actually this was kind of a dream,” he says. “I started thinking how very VIP it was in a way, and how this thing of isolation, of having more space around us, is a kind of luxury.”

In this vein, many of the concepts in Dixon’s draft survival manual are formulated around ideas of overlapping spaces and schedules. “It’s normal to have two shifts in the restaurant, but not currently in the shop,” Dixon explains. “So the idea is that you have fewer people – possibly fewer clients – but you spread them out more evenly.”

This is all explained succinctly in the manual’s introduction: “Who doesn’t know someone who has paid to go on a silent retreat or dreamed in normal times of having more space at the art gallery?” it states. Among the illustrations that fill its pages is an “enclosed isolation booth” for diners. A three-course meal is already laid out on a separate table for them: a cold starter, a hot pot and dessert under a cloche. There are concepts too for a solo disco, plus a high-intensity fitness class for one – the pre-programmed activities triggered as an individual approaches a Tom Dixon x Teenage Engineering chandelier, which sets star jumps and lunges to a “lumière” show. Meanwhile, in the “distancing art gallery”, visitors are given a timer that buzzes every five minutes, signalling their move to the next exhibit, each spaced 4m apart – the tour takes exactly 45 minutes.

Dixon and his staff have tested some ideas in the restaurant, which has been reconfigured to extend into the shop and office spaces to comply with social-distancing regulations. “My initial worry was maintaining that buzzy restaurant atmosphere, but that’s not really destroyed at all. In fact, it’s become quite an upmarket experience,” he says. “There’s something quite nice about people having to get up and fetch their food from a table. I’m a restless person anyway: sitting down for an hour and a half is hell.”

For Dixon, there’s only one moment in a brand’s lifetime to try something different – and this is it. “It might be the only way that parts of the business can survive,” he says. But how will the office function in this brave new world? “There’s been talk about working from home for the past 20 years… People have simply resisted it. If this proves one thing, it’s actually that these things are just human behaviours rather than realities,” he says.

At Dixon’s HQ, the revised office space will be more members’ club than functional work zone. “We designed Shoreditch House 13 years ago, when mobile technology became completely wireless and universal. People very quickly took membership so they had a cheap and very well-serviced and comfortable office in London,” he recalls. “The idea of slouching about and blending pleasure and work really took hold in my head from there.”

He points to emerging practices in China, where workers are split into teams, working at different times without overlapping with other groups. “And, if I extend the hours of the building to midnight, I’ve roughly got a model that works for me,” he adds.

Will there be a “new normal” as we emerge from this imposed hiatus from the modern world? “The only analogy I can think of is airports, where every time there’s a new bomb threat, you get a new level of security – it’s a real hassle for everybody but people conform and they adapt,” he concludes. “It feels a bit like that now. I think everything will be different but everything will be the same. The big hope for a return to normal is that people will over-consume when it’s possible again. But my people see things differently, in that most are happy to spend on essentials but they are holding tight otherwise. Ultimately, as always, it will boil down to economics. We can only wait and see...”

Comments