Lord make me ESG, but not yet

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“The junk merchant doesn’t sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product,” William S Burroughs wrote. “He does not improve and simplify his merchandise. He degrades and simplifies the client.”

Burroughs cared more for heroin than investing and, by dying in 1997, he missed the ESG boom by about two decades. The Naked Lunch author nevertheless offers a fair summary of the ESG marketing industry’s current state: don’t improve the merchandise, simplify the client.

One way that’s happening is to promote the idea that best practice is the enemy of good. Though most tenets of ESG have been diluted into meaninglessness, there’s still a sensible-sounding argument available that says a company showing willingness to improve is worth a place in the portfolio, whether or not it fits the formal criteria. A leap of faith opens a universe of investment possibilities.

Here’s a recent note on “transitioning stocks” from Berenberg analysts Ned Hammond and Ekaterina Naumova:

Investing in transitioning stocks is becoming an increasingly popular approach for ESG funds. This appears to be down to a combination of market conditions being less favourable for expensive, early-stage companies and, more encouragingly, the potential to have a greater real-world impact by owning companies that are not perfect today and engaging with them to improve.

That’s OK, right? Funds with ESG mandates should buy stocks that aren’t ESG because they might be later, and buying them before they gain an ESG premium might encourage the process. It’s logical, as well as being a convenient construction if your business is selling stocks to funds with ESG mandates.

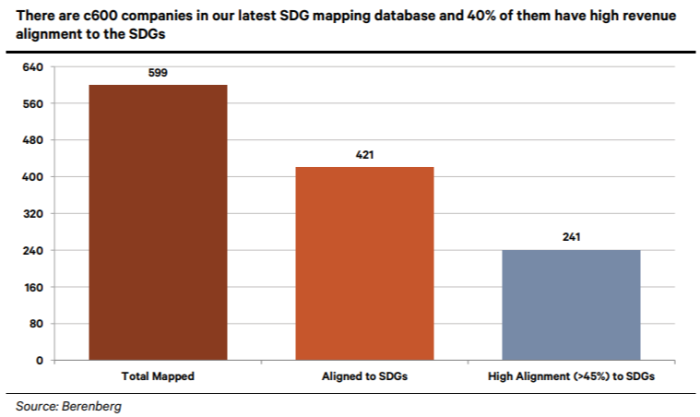

Berenberg this week updated its client database that judges an investment on the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals. If at least 45 per cent of a company’s revenue is tied to something worthy by the UN’s definition, they're good. If the worthy revenue is just 1 per cent or greater, they’re probably fine.

The conclusion is that, of the 600+ stocks covered, about 40 per cent are good and 70 per cent are probably fine:

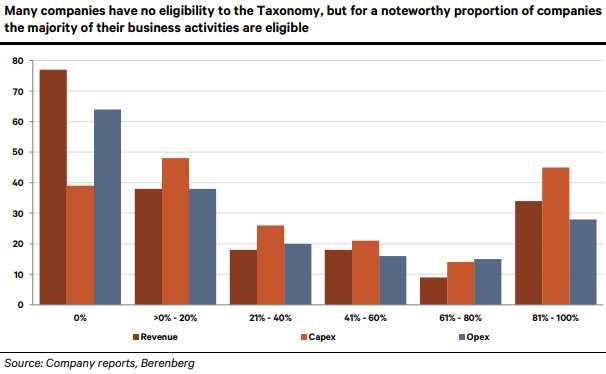

The Berenberg approach takes its cue from EU reporting rules brought into force at the start of 2022. Listed business with more than 500 staff are obliged to publish the percentage of revenue, capital expenditure and operating costs from activities covered by the EU taxonomy of sustainability.

Unfortunately, the EU system is already looking useless. Results so far are nonsense, suggesting little corporate buy-in for filling out the forms.

Asked about their company’s exposure to climate change mitigation and adaptation (the only criterion currently covered by the rule), the most popular answer was zero. Of those to report any contribution, the most popular answer was 81-100 per cent:

And with the EU system a likely victim of garbage-in-garbage-out, brokers can continue to push ESG schema that promise a more nuanced view of the world.

By favouring UN-defined criteria, Berenberg sets a bar that’s both high and wide. No stock in its database is highly aligned to UN goal of eradicating poverty, with only three reaching the 1 per cent of revenue threshold. Improving defenses against natural disasters, protecting oceans and promoting terrestrial biodiversity also score zero by the gold-standard measure.

The more obviously corporate stuff is where stocks score higher, like promoting clean energy, sustainable infrastructure and better housing. These are also where there’s the widest gap between companies rated “good” and “probably fine”. For example, Berenberg finds 45 companies that are gold standard on sustainable industrial processes but there’s another 151 that hit the 1 per cent minimum threshold, and therefore might be going in the right direction.

What’s needed to aid investment decisions is a “direction of travel” column. By that subjective measure, Berenberg can recommend BMW, Ford and Mercedes-Benz as ESG suitable because they sound sincere about clean energy. Waste disposal group Biffa gets the nod because it has shown promise in eradicating hunger. Building company Vinci is getting better at being good for fish, etc.

It’s not alone in handing out Outstanding Progress awards. Here’s a note published Thursday by Barclays on Glencore, the world’s biggest shipper of coal to power stations:

We see Glencore as having most upside potential from improved ESG performance: Historically, investors have often tended to see Glencore as an ESG laggard, but we have seen material improvement in recent years such as: 1) improved safety performance; 2) monetising high ESG risk assets into strong markets; 3) enhanced governance and alignment with shareholders; 4) strengthened compliance and risk mitigation

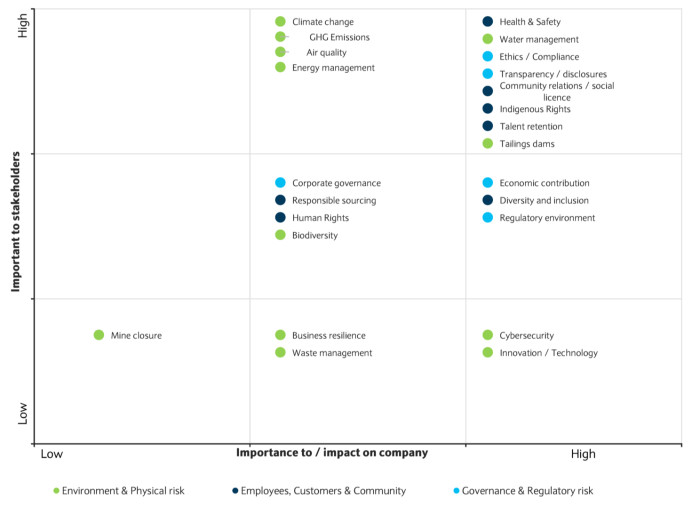

Rationalising the various ESG concerns around Glencore requires 48 pages and a fret alignment table . . .

. . . the gist of which is that things are getting better where it matters. Glencore has pledged to cut coal production in half by 2035 versus the 2019 level, and corrective actions from its more than a decade of bribery and market manipulation have resulted in a better corporate culture.

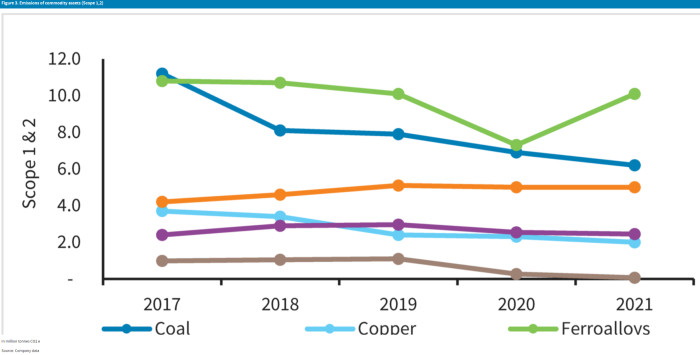

And while Barclays concedes that carbon emissions have been stubbornly high due to coal and downstream processing . . .

. . . management says carbon by Scope 1-3 measures will be down 50 per cent by 2035. What matters most here is the direction of travel.

A reminder that Glencore has rejected calls to spin off the coal division in favour of a multi-decade runoff process. Barclays puts forward the argument that an independent coal company would be more motivated to sustain production (like Thungela Resources has done post its split from Anglo American) though most of its work on coal is about cash returns. An estimated 65 per cent of Glencore’s free cashflow next year will come from coal so getting rid of that would be, from a pragmatic perspective, bad.

“The share price has, in our view, ignored the improvements in ESG over the past year, with Glencore trading at a 40 per cent 2023E P/E discount to diversified peers,” says Barclays — from which the conclusion might be that anything is ESG if it looks cheap enough.

Further reading . . .

Naked Lunch (excerpt) — Goodreads

Comments