Shipping funds: plain sailing for investors?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Owners of aircraft had a tough period during the pandemic but ship owners have been steaming ahead — and for investors eyeing this sector, there appears to be still more upside on the horizon.

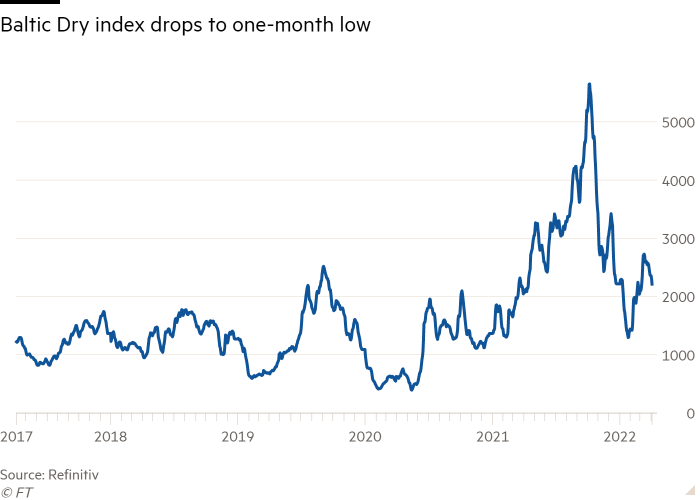

Key measures of shipping activity such as the Baltic Exchange Dry index shot up in the pandemic recovery, peaking at levels not seen since the early 2000s. That index has now fallen back but remains at elevated levels.

A flotilla of publicly listed shipping businesses, ranging from funds through to the likes of Clarkson, a ship broker, have seen their share prices rocket. The listed funds segment of the London market has been a particular favourite as income-focused investors have backed two ship-owning, asset-backed funds: Tufton Oceanic Assets, which floated in 2018, and Taylor Maritime Investments, which listed last year. I have holdings in both.

These closed-end investment companies have experienced rapid share price appreciation. This has pushed their once generous dividend yields of 7 per cent down to slightly less adventurous levels of 4.9 and 5.9 per cent respectively. Cynics might presume that the best is behind these funds as shipping markets stabilise — and possibly even cool off, should we see an energy induced recession — but I think they might still reward the patient investor.

It is important to understand the characteristics of the two funds. Both started off as income-focused vehicles but benefited from a substantial uplift in net asset value as their ships appreciated in value. This meant both have been busy raising extra capital in recent months.

They have been canny about buying the right kind of second-hand ship — the average fleet age of Taylor Maritime’s fleet is 11 years — and then trading ships as purchase prices have shot up. Tufton recently divested the container ship Vicuna for $18mn, realising a net internal rate of return of 46 per cent in a matter of a few years.

Both have avoided the pitfalls of previous listed, asset-backed income vehicles — aircraft leasing funds, for instance — which used complex financial engineering involving lashings of debt and a layer of equity on top. Both also have a large fleet of ships — Tufton with 19 last time I counted, Taylor Maritime 30 — which aren’t as state of the art as the aircraft leasing funds’ massive, gleaming A380s.

The funds have also avoided the dependence on just one big lessor and have fairly short charter durations ranging between a few months and a few years.

But there are crucial differences between them. Tufton has a more diversified portfolio of ships including an early emphasis on container ships, as well as chemical tankers and bulk carriers in the smaller category known as Handysize. Taylor Maritime is heavily focused on Handysize bulk carriers and has also invested a fair amount of capital in a separate entity called Grindrod Shipping, an international shipping company listed in the US and South Africa, which owns a modern fleet of 25 predominantly Japanese-built geared dry bulk vessels.

Again, some readers might well acknowledge these subtleties but pose a more basic question. Aren’t we past the best of the cycle and now into a more difficult spell? There’s no doubt the pace of activity has cooled. But Edward Buttery, chief executive of Taylor Maritime, points to substantial upside in the data on his Handysize bulker segment. This shows that congestion at ports is still at heightened levels, with not enough ships to go around. His prediction is that the current strong market will persist through to at least “2023 and beyond”.

That rosy forecast does not, of course, cover another risk: a sudden flood of new ships being ordered and chartered out. Buttery’s response is that the bulker ship segment has not been prey to the overcapacity binges typical of the container ships sector.

Looking at new ship orders he observes that “the Handysize order book remains the tightest of all dry bulk sectors. It is worth noting that the lack of capacity in shipyards is such that even if ship owners wanted to, they could not order more than a handful of ships before 2024.”

Another risk is the duration of charter periods. Taylor seems to have shorter duration contracts, largely because that’s where the market is currently paying the highest rates. Tufton appears to have slightly longer durations, with the average expected charter length running at 1.9 years. If demand were suddenly to freeze up, Taylor might be more vulnerable.

Another risk is that older bulk and tanker ships operated by Tufton and Taylor Maritime suddenly become uneconomic because of tougher environmental regulations. Both funds are investing heavily in upgrading their ships — for instance, to use biofuels — but there’s no obvious answer to the rapid need to decarbonise the fleets.

Most progress is likely to be around progressively replacing fossil fuels with alternative low or no-carbon fuel, such as methanol and ammonia. In the meantime, the owners of newer vessels with better fuel efficiencies are likely to be the beneficiaries — and both funds score highly on this measure.

I remain optimistic. Both funds are churning out cash because of high returns on assets deployed. Tufton currently boasts a run rate yield on its fleet of 14 per cent. And there may be more upside to come on the value of those ships. The funds team at investment bank Jefferies have been running their slide rule over the two fleets and reckon both might be worth substantially more than is stated.

Using data from Clarksons, they reckon that average second-hand price of a 10-year-old Handysize vessel has increased from $17mn at the end of 2021 to $18.5mn currently, which could imply a $35mn uplift in net asset value (NAV) for Taylor. This gives an estimated NAV of $1.73 a share, implying the shares trade at an 18 per cent discount.

As for Tufton, the analysts have tentatively added another $20mn NAV uplift on their more mixed fleet, implying a NAV of $1.44 a share, which in turn equates to a 5.8 per cent discount. Jefferies also notes that the big Japanese shipyards are sharply pushing up prices on new ships to pay for extra energy and steel costs, thus supporting the price of existing ships.

The rather mundane segments of the shipping market targeted by both funds have had bad decades in the past. There was a decade-long downturn in bulker rates before the current boom. And all the talk of strong asset backing could be pie in the sky if there is a sudden economic slowdown.

But on balance I think there remains real potential for an uplift in values. And don’t forget those well-covered dividend payouts, which should satisfy the income-hungry investor.

David Stevenson is an active private investor and has interests in securities where mentioned. Email: adventurous@ft.com. Twitter: @advinvestor

Comments