The mystery and magnetism of Geoffrey Bawa

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Two hours south of Colombo: the motorways have become roads, the roads lanes. There is the sense that we’re getting near: nature becoming more protective, the houses fewer, the scent of prosperity. And suddenly here are the gates and a security guard with “Efficient Staff” proudly embroidered on his shirt. The drive winds up through jungle proper and there waiting for us are white-linened Menarka, the manager, and his staff.

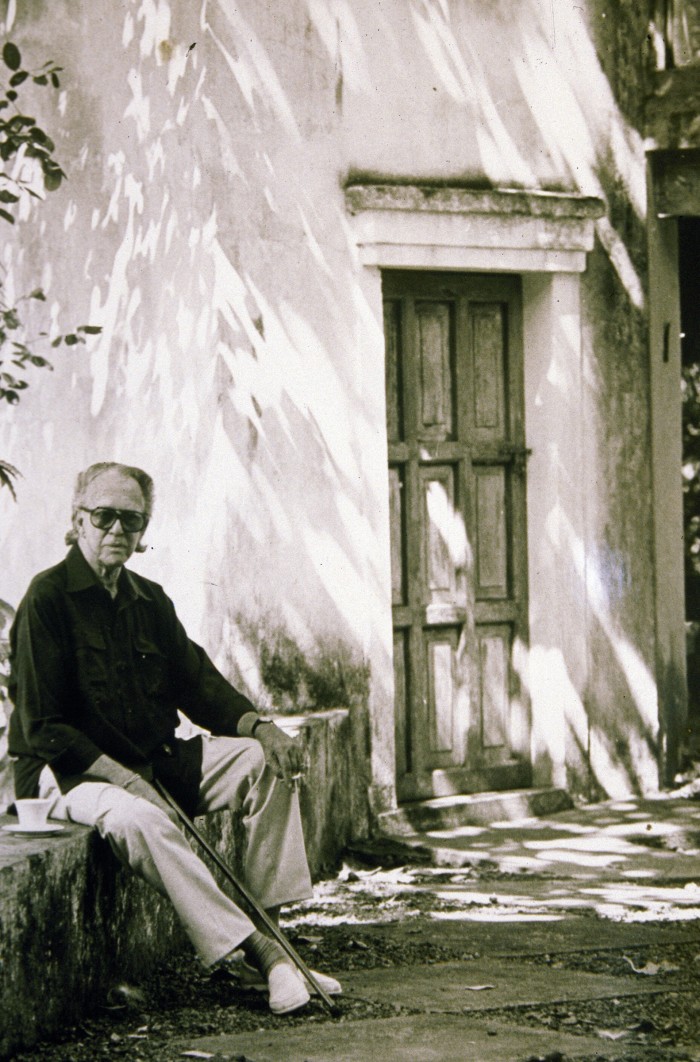

I have come to Sri Lanka in search of Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003) and we are staying at Lunuganga, his country house – now a hotel of just nine rooms and suites run by Teardrop Hotels for the Bawa Trust. Bawa’s work has long been recommended to me by both traditional and modernist architects, which never happens. I know it well from the books on my shelves. Writing – and photographing – a book of my own, on my work and its inspirations has brought me to Sri Lanka in person.

I have travelled here with Harry Crowder, the book’s photographer, and my colleague Scarlett. Our travel has taken place a year later than planned – Sri Lanka’s borders were closed to non-nationals during Covid. And we are here before the country falls into crisis. As it is, we have Lunuganga to ourselves.

Lunuganga (“salt river”), the reason for the trip. The journey from Colombo, travelled by Bawa in his ’30s Rolls-Royce, and by us in a Toyota Hi-Ace with an over-enthusiastic driver who stops by the roadside to make us drink coconut water straight from the shell. (I am too English to say I don’t much like it, but the others don’t mind.) Menarka has predicted correctly which room we will each select: Scarlett in Bawa’s Guest Suite in the main house, Harry in the remote Gate House Suite, which opens out into the land should inspiration take him, and me in the room formed from Bawa’s private art gallery, lower down.

Late lunch and tea on the terrace; freshly baked cake still warm. Breaking our fast dispels the post-flight stupor. And then we wander out into the gardens, conversation dissolving into awed silence. Harry seeing things through his lens-eye. Me analysing. Scarlett most at home, floating in a shirt dress, cup of chai in hand.

Floating is a word I want to use a lot at Lunuganga. Born in Colombo in 1919 to a wealthy lawyer father and Burgher mother, with European, Sinhalese, German and Scottish blood, Bawa studied law in the ’30s at Cambridge and later architecture in London. He had intended to buy an estate in Italy. Then Sri Lanka became independent, or maybe he found his money didn’t go so far in Europe, and in 1948 he came home and bought this land – 25 acres across a promontory into the Dedduwa lake, near the coast at Bentota. For the next 50 years his career developed, culminating in receiving, over lunch one day, the commission to design Sri Lanka’s new parliament building. His influence quietly spread around the world such that any sensitively designed hotel you stay in today probably owes a debt to Bawa, who showed that it was possible for architecture to respond to local specifics of climate and culture while also being part of a bigger movement of optimism. And for those 50 years, Lunuganga was Bawa’s private world where he experimented for himself, cutting swaths through the jungle to open up views of the lake below the old colonial house, and building a series of pavilions in the grounds.

Bawa gardened by megaphone. The house and driveway were reordered, a road across his to the next property hidden behind a ha-ha. Paths were cut and terraces formed. What was the entrance became the garden terrace, pinned around a frangipani tree; actually two, grafted together, whose branches were weighed down to give them their generous spread. Is this the definition of posh?

On the other side of the house, Bawa had the hill lowered so he could see the lake from his breakfast table by the front door. Pretty posh too. From behind the baroque terrace edge, one of a well of European references filtering through, the birds soaring around you, there is the sense of nature held at one remove, seen from above.

We dine and collapse. I wake at 6.30am with the light; but it is a subdued light, no sun. Half an hour thinking the trip is cursed, the book is cursed, I am cursed, as I doze. (Why does the mind do this?) When I wake properly, the sun is out, the curse lifted. I walk up to the house. Harry is out, shooting, seen from afar with his tripod. He shoots from dawn to dusk. He has befriended the chef who says he will cook whatever we like – hottest curry for the others, mildest fish for me. I have smuggled in some gin (not having a liquor licence, the hotel is dry).

The next morning is grey-tinged again, but we have our shots. Scarlett departs for London; Harry and I can’t bring ourselves to leave this place and stay another night. I move to the Glass Room, a glazed corridor of a space raised up above the entrance courtyard. Staying in Bawa’s house, among his beautiful collection of things, in this place where he made manifest his thoughts, I feel I’m getting to know him. There are staff here who worked for him when he was still alive. All have respect. There are nine gardeners; their rhythmic gravel-sweeping feels part of the creation.

Salt river. The water is the essence of the place. There are dragons in the ponds, crocodiles in the lake. It is otherworldly. To be in Bawa’s garden is to be conscious of space, of time, of movement, of nature, of self.

We begin to conceive of leaving. Sri Lanka is empty enough that we are able to travel as I like to, which can be summed up as “make it up as you go along”: a luxury. On the way to Colombo we stop at Bawa’s Bentota Beach Hotel, one of the first he designed; the hotel that defined his local-international architecture. You enter from a stone undercroft up into the middle of the lobby, against a courtyard of water with trees growing through it. It feels Sri Lankan. I wouldn’t really want to stay here, though we missed the Club Villa Bentota, where I might if Lunuganga was full.

We are heading to the capital to see Bawa’s townhouse, known as Number 11, also managed by the Bawa Trust and where it is also possible to stay, except someone has taken it for a month. Number 11 was developed over the same period as Lunuganga, from four houses into one. Harry and I are childishly excited. And then frustrated – no photography beyond the hallway. We begin negotiations.

In contrast to Lunuganga, which is all about views out, Number 11, the other side of Bawa’s psyche, is entirely contained, except for the second-floor roof terrace that once looked out to the sea, the view long blocked. It is an exquisite house, full of exquisite things. A hallway of white floors, then private rooms opening into courtyards, water trickling. The long first-floor sitting room, with its white shag-pile rugs, plastic furniture and Balinese tapestry wall, is possibly the coolest room I’ve ever been in.

We have a night in Colombo, a wonderful exhibition of Bawa’s drawings, and a drink with the curator Shayari de Silva, who secures Harry more film, delivered as we are eating dinner at The Gallery Café in Bawa’s old office, in retrospect possibly looking very much like a drug deal. With hints of what is to come politically, our hotel looks out over the port that is being filled in by China, to whom Sri Lanka has inadvertently handed ownership.

An early start to catch the train to Kandalama, the kilometre-long hotel near Dambulla in the middle of a nature reserve that Bawa designed in 1990, one of his last works. Calls ahead made by Number 11 mean I have been given Bawa’s favourite room, 507, at the angle on the top floor. Bawa’s genius here was to site the hotel hard against the cliff face, with the corridors open to the cool rock. And also to cover the building in creeper, in which monkeys climb, several just outside my room while I bathe (there are instructions not to open your terrace doors or they steal your things).

The next day the sky is hazy. I walk the corridors and write. I think I am beginning to understand Bawa, architect to architect. He doesn’t sweat the small stuff. It’s all about placement and rightness, inevitability. You always feel comfortable. Perhaps this is his upbringing, privileged: an unexpected democrat, he seems to expect it for all of us.

At nine o’clock on our last night, Number 11 confirms that we can shoot; at six the next morning we are on our way. We have it to ourselves for an hour with the curator, and the last two precious rolls of film. As we leave for the airport, we meet a Bawa trustee, an architect who worked in his office. I dare to ask what I have wanted to all through the trip: was he a nice person? Gentle and shy, the answer. Did he have a temper? When annoyed, he would say, “Damn and blast”, and then there would be silence. I am relieved. I think I would have liked Bawa, the simple, complicated, determined man who quietly created a country’s architecture.

William Smalley was a guest of Lunuganga, rooms from $230. Number 11, double rooms from $300. Kandalama, room 507 from $200. The author’s book Quiet Spaces will be published by Thames & Hudson in 2023

Comments