‘I wanted to keep them close . . .’

Simply sign up to the Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“Everything we love is about to die, and that is why everything we love must be summed up, with all the high emotion of farewell, in something so beautiful we shall never forget it.” French surrealist writer Michel Leiris’s words, writ large on the final wall of Tate Modern’s 2018 exhibition Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy, are etched in my mind. That was the year I had two consecutive miscarriages and not a clue how, or even if, I wanted to commemorate those two little souls.

I didn’t need a visual reminder of that painful loss, but in time I wanted to keep them close to me, acknowledged in some tiny way alongside my living children. It’s a personal feeling that others may not relate to, I concede. In lots of ways, grief is much like art; entirely personal to the individual. For some, in mourning, there is a natural desire to create tributes, commission artworks, erect monuments, name species in memory of someone who has died, as a means of holding on. But not knowing how to create a tangible and enduring tribute is where that intention can fizzle out.

Those who wish to make a celebration of those whose lives have been lost might turn to John Booth. The ceramic artist creates bespoke urns in bright hues and lively brushstrokes, taking private commissions (from £3,500) inspired by an individual’s personality and interests. Booth was originally asked to create a limited-edition collection for the “death experts” Farewill, but during his research, everything he found was “boring and a bit sad”.

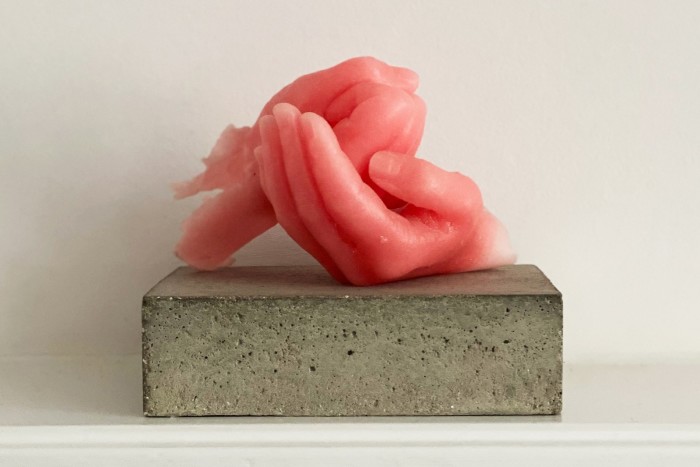

“Art can be used as a positive path through grief,” says mixed-media artist and art psychotherapist Lisa Snook, who lost her brother seven years ago. Her wax hands sculpture, cast using her own hands, expresses “the tension of holding onto grief in a very muscular way, bracing my body against the pain of loss in the clenched fist, and then of letting go, relinquishing the control of loss in the open palm, acceptance.”

Snook’s artwork of 40 bisque-fired porcelain bones, each bearing the marks and texture of skin, also represent the psychological fragmentation of grief, a feeling of being blown apart. “As a collection they have a forensic feel, laid out for examination, an archaeological site of grief,” she explains. A member of the Royal Society of Sculptors, Snook weaves philosophical notions of memento mori, reflections on death and mortality into her commissions (from £500). In her psychotherapeutic work she also supports clients through the grieving process, using art as “a conduit or vehicle to communicate the deep sorrow that is so profound, often there are no words to express it.”

For years, artist Jason Shulman wanted to commemorate his late friend Shaun Lawlor, who took his own life during their art-school years. “He was very influential to me and I had always wanted to make a piece worthy of his influence and his fine mind,” he says. A chance reading of a Victorian parlour games book sparked an idea. It read: “If you want to make a magic rabbit appear, get some acid and paint it on a bit of glass. Your friends won’t be able to see the image until you breathe on it and then a rabbit will appear.” A few chemistry experiments later, Shulman had it figured out. “I thought, God, this would be marvellous for commemorating people.”

Designed to hang on the wall, Shulman’s ceremonial “mirror” is designed as a black funerary box. Opening the framed door reveals a little mirror and one’s own reflection. Breathe on the mirror and an image of the person who has died appears only for a few seconds before slowly fading away as the breath evaporates. All that remains is one’s own reflection, and the door is replaced. “It’s a little meditation, really. It’s designed to make you focus your concentration on the person you have lost; a classic memento mori in a way.” Shulman has created a number of breath mirrors, including of his late father, the theatre critic Milton Shulman.

Brothers Ian and Richard Abell of Based Upon create large-scale artworks and sculptural furniture, often to honour the dead. One such piece, Scottish Highlands, was conceived in part as a tribute to a client’s late father, for which Ian and his 45-strong team mined inspiration from the family estate in Scotland. Key to the piece is a cross, a talisman found by the father’s bedside, a copy of which was set into a resin replica of the peaty burn running through the estate, along with stones gathered from the Scottish riverbed.

All the artists hope their work might offer clients some kind of closure. Ultimately, says Shulman, the final artwork commemorating a life can be “so much more than the sum of its parts”. With rich investment of time and thought, Snook and the Abells also emphasise that the process can be as important as the final commemorative piece.

As for my memento mori, I have my eye on Martha Freud’s porcelain vessels imprinted with messages or objects, which can be lit from within. A ceramicist inspired by nature, Freud also takes commissions for foetus portraits in volcanic sand on porcelain, working off 12-week scan photographs. For me, having the interactive element of light within the artwork finds just the right balance of grief, hope and joy.

Comments