Future of the City: London’s markets rivalry with EU intensifies

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is part of a series on the Future of the City of London

Appearing in front of the Irish parliament last week, Mairead McGuinness, the EU’s financial services chief, laid out the bloc’s uncompromising stance towards the UK’s largest services export.

“If a state opts out, there are consequences to that. There are consequences for the City of London which players and stakeholders there are well aware of,” she told the Dáil.

With the UK set to exit the single market on January 1, banks, exchanges and fund managers are poised for the end of an era of seamless market access that helped turn the City into Europe’s financial supermarket and handed £76bn in tax receipts to the UK government last year.

With a trade deal yet to be agreed, senior executives realise that the City of London will probably have only pared back and inefficient access to EU customers when the transition period ends.

Some jobs, trading and assets will transfer into the bloc as the market splits. Even so, financial companies are putting faith in the UK’s heft as a global trading centre to hold on to most of it.

“I’m not in the camp that feels that London has lost its mojo. I have a lot of confidence in London and its positioning,” said David Schwimmer, chief executive of London Stock Exchange Group. “Brexit has not been helpful but it doesn’t change the fact that it has a winning combination.”

Since the referendum the EU has sought to ensure that Britain would not be able “cherry pick” the benefits of the single market for its prized financial services. Holding on to “passporting” rights, which enable banks and trading venues to offer financial services across the EU, was quickly ruled out. The industry was largely omitted from the trade talks.

Instead, Brussels successfully insisted that future co-operation be based on the same legal process it uses to manage cross-border activity with other countries such as the US and Japan.

The system, known as equivalence, relies on the UK and EU judging each other’s regulation and supervision to be as good as its own.

Access rights are granted unilaterally, can be withdrawn at short notice, and provide less comprehensive arrangements than single-market membership.

Moreover, they are piecemeal. Among the glaring omissions is the fact that the system does not cover basic banking or retail investment funds. There is no automatic recognition of qualifications of crucial ancillary financial services work, such as law.

Still, it does help to facilitate cross-border trading in shares and derivatives, as well as the provision of brokerage services. Paul Myners, the former City minister, describes equivalence as “very short-term. It’s like building a house on sand”.

Business not covered by equivalence will rely on bilateral deals between the UK and individual member states that the European Commission has sought to limit.

The City is likely to start with only a handful of these permits at best, even though it will meet the requirements and Britain has made some concessions, for example allowing UK customers to use EU services such as exchanges, clearing houses and financial benchmarks.

Brussels is yet to provide assurances about how much of this unstable patchwork will cover the UK. It has already deferred a decision on cross-border investment banking services, saying its own regulations are still bedding down. It has limited its actions to those necessary to prevent financial turmoil.

Diplomats say the EU’s stance reflects a mixture of negotiating tactics connected to the two sides’ future-relationship talks, a political agenda to become financially less reliant on the City, and concerns about handing rights to a country seeking to break away from EU rules.

Karel Lannoo, chief executive of European think-tank CEPS, said the UK and EU had conflicting views on a host of issues, including bonuses, bank resolution and securities trading.

“Divergence will start rapidly in many fields, making equivalence even more difficult,” he said.

Future of the City

In a series of articles, the FT examines how London’s financial centre will fare in the decades ahead as Brexit negotiations reach their climax

Receive alerts when a new part of this series is published by adding 'London fights for its future' to myFT

Without guarantees on access and the EU refusing “letterbox” relocations that employed a skeleton staff, financial companies with headquarters in London have set up local operations.

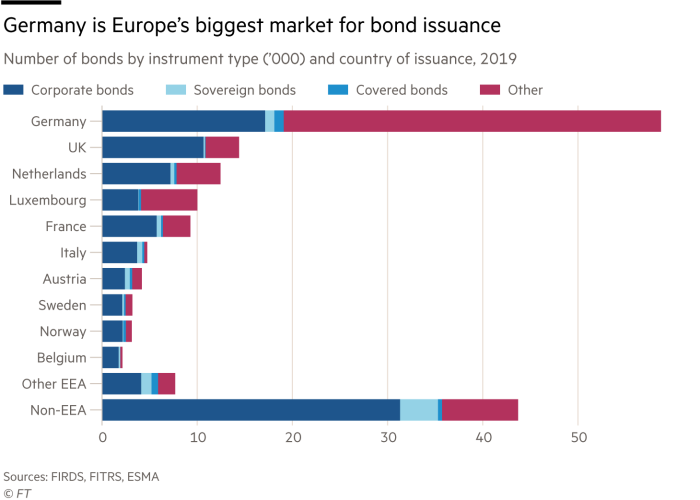

Banks opened subsidiaries in Frankfurt, Paris and Madrid, trading venues turned to Amsterdam, asset managers to Dublin and Luxembourg, and back-office business to Warsaw.

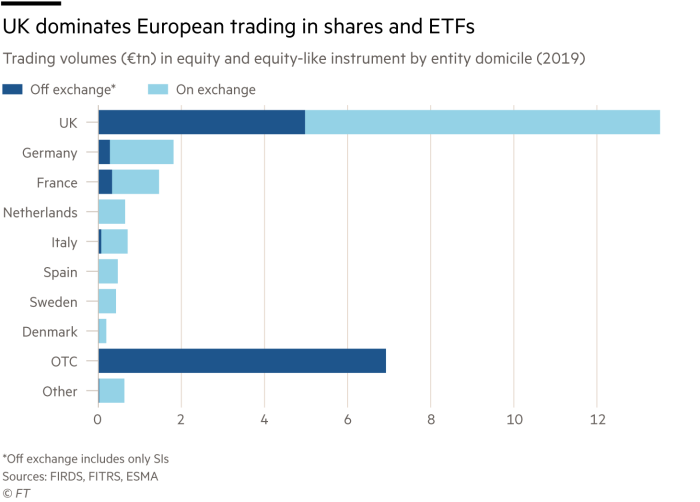

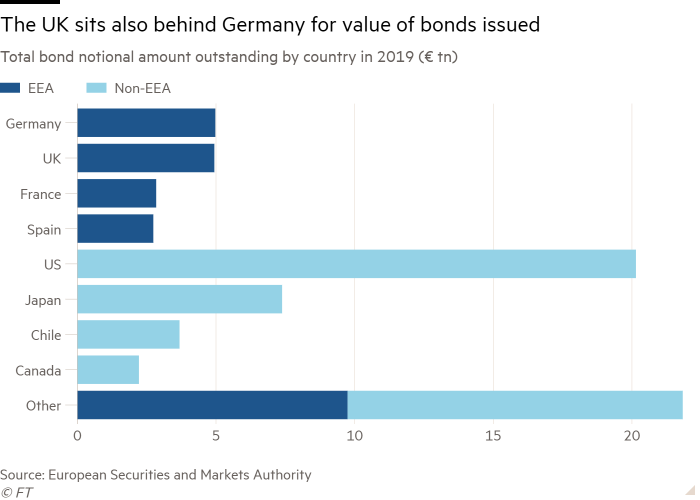

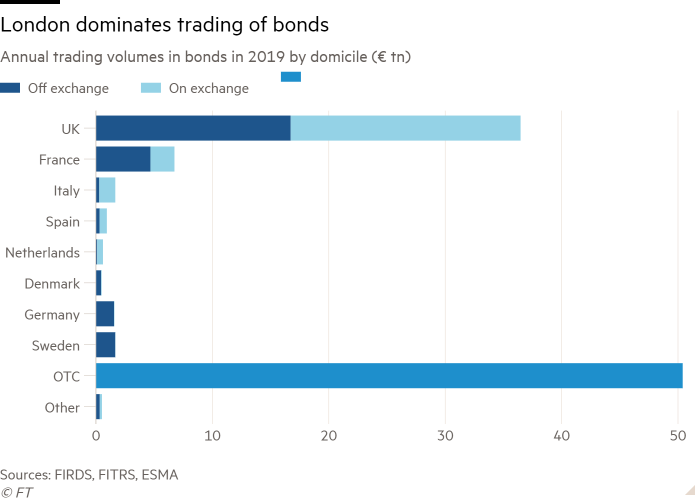

Some business has already moved: EY estimates banks have shifted €1.6tn of assets, and sovereign debt trading that would typically take place on venues in London is now in Amsterdam and Milan. More than £4bn of insurance premium income in 2019 that would typically be handled in London was written in new hubs such as Brussels. That outflow will be supplemented by share, derivatives and bond trading after the market splits in January.

The failure to resolve arrangements on cross-border business means parts of the market face disruption on January 1. About a sixth of London’s $1.2tn a day interest rate swaps market is particularly at risk, the Bank of England warned last week.

The business may go to the US to work around the regulatory barriers, said Emma Tan, vice-president of regulatory affairs at JPMorgan.

Fintech, covering payments and online lending, largely lies outside the scope of equivalence, forcing many companies to set up operations in the EU. However, they need an agreement to guarantee the flow of personal data, which affects everything from the use of customer details to using cloud computing services. “We have to be able to share data across borders as the fintech world is cross-border,” said Charlotte Crosswell, chief executive of Innovate Finance, a lobby group.

EU capital markets will shrink after January from just over a fifth of global activity to just 13 per cent, the same size as China, according to New Financial, a London think-tank.

That decline may allow London’s financial muscle to reassert itself in the short-term. While some jobs have been moved out, others have moved in. Bovill, a regulatory consultancy, found that more than 1,400 EU-based companies have applied for permission to operate in the UK after Brexit.

Moreover the City’s contemporary success is in part based on being a hub for global markets, dominating insurance underwriting and trading in currencies and derivatives. That activity has swelled since the referendum.

A deep market makes it easier for investors to buy and sell their assets at more competitive prices, pulling in more business and people to service it.

Capital flows across borders. Asset managers have set up local EU operations but retail investment rules allow £2tn of EU funds to be managed from London. Investment banks’ trading desks often “follow the sun” — handing over supervision of vast derivatives and currency portfolios with deals worth billions of dollars to colleagues in different time zones. London sits at the heart of this global network, catching the end of the Asian trading day and morning on Wall Street. EU trade is sometimes only a fraction of these markets.

EU consumers face higher energy costs and its companies “substantial limits” if they are shut out of commodity markets that only exist in London, European energy lobby groups have warned.

“European companies want access to the most liquid markets in the world. It may be that commercial logic trumps political considerations,” said Jonathan Herbst, partner at London law firm Norton Rose Fulbright.

Clearing and settlement are the only activities for which Brussels has granted the UK temporary equivalence, because a sudden loss of access would threaten the stability of the financial system. London handles about 90 per cent of all deals in clearing houses such as LCH and ICE Clear Europe, which prevent a default from creating a chain reaction across markets.

The EU has made clear that the reliance on the City is intolerable and expects banks to move their euro-denominated trades into the bloc by mid-2022.

Yet the market has not moved in four years. Banks and their customers prefer to keep their business in one place because they can net their positions and save billions of dollars in the margin needed to support their positions.

Robbert Booij, chief executive, Europe at ABN Amro Clearing Bank, said banks such as his needed access to London clearing houses or they would be at a “severe competitive disadvantage” compared to UK and US rivals.

Britain may about to leave the EU but the long-term relationship between the two will take several years to resolve.

Additional reporting by Jim Brunsden in Brussels and Owen Walker in London

Comments