The meditative art of tea-making

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Somehow, after 20 years working as a magazine editor for design and fashion publications, I’ve ended up tending to a tiny-scale herbal-tea business. This was certainly not part of any plan, or how I ever imagined things going for myself. But one year, I dried some herbs from my small vegetable plot – chamomile, mint, lemon verbena, lemon thyme, lemon balm and others – and blended them in jars as gifts for friends. The response was so overwhelming that I was prodded by one rather forceful friend into doing it again the next year – and after that, into selling it: an edition of 350, called Garden Tea ($28).

Tisanes are made of any mixture of dried leaves, flowers, fruits or seeds, infused in hot water and then strained. Thanks in large part to the wellness movement, their consumption is on the rise worldwide. Herbal teas are entirely natural, calorie- and caffeine-free, calming, stress reducing, and even supposedly fat-burning. After a year of eating our way through the stress of illness and lockdowns, the market for herbal teas seems poised to outperform even the upswing predicted by the predictors of such things. (Oreos also had a banner year.) It is expected to grow by more than 17 per cent by 2027, and contribute to making the global organic-tea market an estimated $1.12bn business.

But I got into this game for exactly none of those reasons. When I was growing up in the late ’70s, there was a popular television commercial for Ortega-brand taco shells in which some of the people liked making the tacos, blending the ingredients, and others just liked eating them. I just like making tea. Even when the work is repetitive, as with plucking dried leaves from their stems, working with aromatic plants never fails to make me that little bit happier.

Producing one’s own herbal tea involves nothing more than planting, harvesting, drying and blending the herbs of one’s choice. As any gardener knows, these useful plants are among the easiest to grow, as most hail from the dry, rocky Mediterranean, and not only resist coddling but prefer to be ignored. Yet each type of plant is different in its fragrance, taste and disposition, which accounts for the distinct joys in working with each of them. If I had to pick a favourite, the tiny, daisy-like chamomile flower – with its sweet, apple- scented perfume that releases when you comb your hand up their stems to pop the flower heads off – might be the winner. Another fantastic herb is lemon verbena, perhaps the most divine lemon fragrance in the plant world, harvested for its leaves only. Every time you brush past it, living or dried, it offers up its wonderful, mood-enhancing aroma. A delicious blend could be made from these two partners alone.

As simple as it is to make one’s own herbal-tea blend, the process unfolds over many months. Some herbs, such as calendula and chamomile, are best started from seed around now; others can be bought as seedlings, and will return in subsequent years – or, in the case of the mints, spread farther and wider each year. Still others, like lemon verbena, won’t survive the harsh winters of upstate New York, and so sit out the cold in my cellar before going back into the ground in late spring.

Harvesting takes place from spring until the first frosts. Herbs are best collected in the early morning after the dew has dried but before the sun starts to leach their scent. During lockdown, I loved going out in the mornings to check up on the plants and decide which to collect that day and dry in open baskets or hang in bunches from a line strung across my studio. Often at night, after dinner, I would remain at the kitchen table, picking off leaves or flowers from dried plants and storing them in jars. So, all in all, I was messing around with these plants for the better part of nine months.

This interaction with the plants – indeed, this relationship – across months and seasons accounts for yet another reason I find making tea so compelling. I used to feel I could cheat the melancholy that came each year with the passing of spring’s first flush of cheering daffodils and flowering fruit trees, as I drove from New York City to my house an hour north in the Hudson Highlands. When the spring bulbs in the city became waterlogged and mucky and the trees started to push out their leaves and drop their flowers, I could watch the season unfold backwards going north. Back home, spring was two weeks behind, and the curtain would just be rising on the same show that had recently ended.

Gardening has always seemed to me a way of inserting yourself into the uncaring passage of time as it moves heedlessly along. As a gardener, you are constantly wedging yourself into this great cycle, albeit on a little patch. You get to engage and reckon with nature’s vicissitudes, and closely observe its floral comings and goings. Growing tea, as with growing flowers or vegetables, is yet another way of putting yourself in nature’s way.

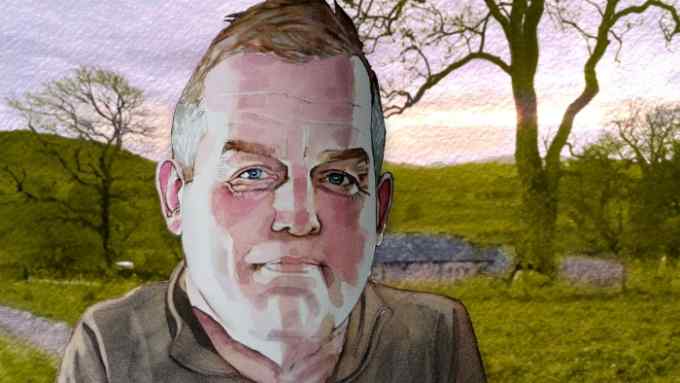

But from running glamorous magazines to pulling leaves off desiccated plants? Over the course of my career, I was editor of three publications, each of which reached a vast audience. What I adored most as an editor – and what motivated me – was celebrating the work of other people. But as I slid past 50, I began to crave the freedom to do my own work, on my own schedule, in sync with the actual seasons, rather than the fashion seasons. Also, an unfamiliar desire arose in me to make use of my hands as well as my mind. A magazine, or any product made by many people, is a collaborative endeavour, wonderfully so. And by its nature, it can be bigger, better and far more influential than anything I can do on my own. But so too is it diffuse.

I set off from my last job to learn to make baskets, with the idea of growing my own willow so that I could take part in every aspect of the object’s creation. Growing and making herbal tea is likewise a small closed circle of production. Craft, or the making of anything by hand, whether a ceramic bowl, or a meal, a basket or a batch of tea, has a scale of 1:1. Each bag of tea passes directly from me to one other person. Its impact is minuscule, and entirely satisfying.

Available at The Little Shop at Fowey Hall, foweyhallhotel.co.uk, and reedsmythe.com

Comments