Gallerist Hannah Traore: ‘I break rules I don’t even know I’m breaking’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When we meet, Hannah Traore is celebrating a birthday: her eponymous gallery, a lively enterprise on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, has just turned one. Traore, 28, opened the gallery in January 2022 with a mission to highlight artists who have been historically overlooked because they hold a marginalised identity, their work doesn’t fit a certain mould or, often, both.

“I’m not checking off a box, and I’m not trying to prove that I am showing diverse perspectives,” she says. “I am a diverse perspective.” She draws inspiration from black women who have blazed a path in the white-dominated gallery industry, including Nicola Vassell, an art-world mover who opened a Chelsea gallery in 2021, and Linda Goode Bryant, whose pioneering gallery Just Above Midtown, which was operational from 1974 to 1986, is currently the subject of an exhibition at MoMA.

Her gallery now has eight exhibitions under its belt, including shows of work by New York-based Colombian photographer Camila Falquez and Toronto artist-illustrator Moya Garrison-Msingwana — both of whom will be highlighted in the gallery’s inaugural booth at Frieze Art Fair in Los Angeles next week.

Traore was surrounded by art from a young age. She grew up in Toronto, where her mother, a fibre artist with a passion for collecting west African art, ensured that museum visits were a regular occurrence and enrolled her children in ceramics, painting and photography classes. “Art was deeply respected; it was never viewed as frivolous,” says Traore.

For her undergraduate art history thesis, Traore curated the exhibition Africa Pop Studio at Skidmore College’s Tang Teaching Museum. The show, which included work by Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, featured pieces by some of the most notable names in contemporary art, including Mickalene Thomas, Derrick Adams and Kehinde Wiley, who painted Barack Obama’s presidential portrait the following year. The star-studded exhibition was a high-reaching undertaking for any novice curator, much less a college student, and prompted even bigger ambitions. “That was when the idea of opening my own space started swirling in my head,” says Traore.

Art-world jobs, including a curatorial internship at MoMA and a stint as an organiser of exhibitions and events at Fotografiska, the photography space, followed. Yet Traore never worked in a commercial art gallery until she founded her own: a blessing and a curse, she says, as it has allowed her to “break rules I don’t even know I’m breaking”. The gallery feels accessible to connoisseurs and novices alike, and her programme often highlights artists who are better known — and popular, if Instagram follower counts are any indication — in fields that can seem less rarefied, such as illustration, fashion and craft.

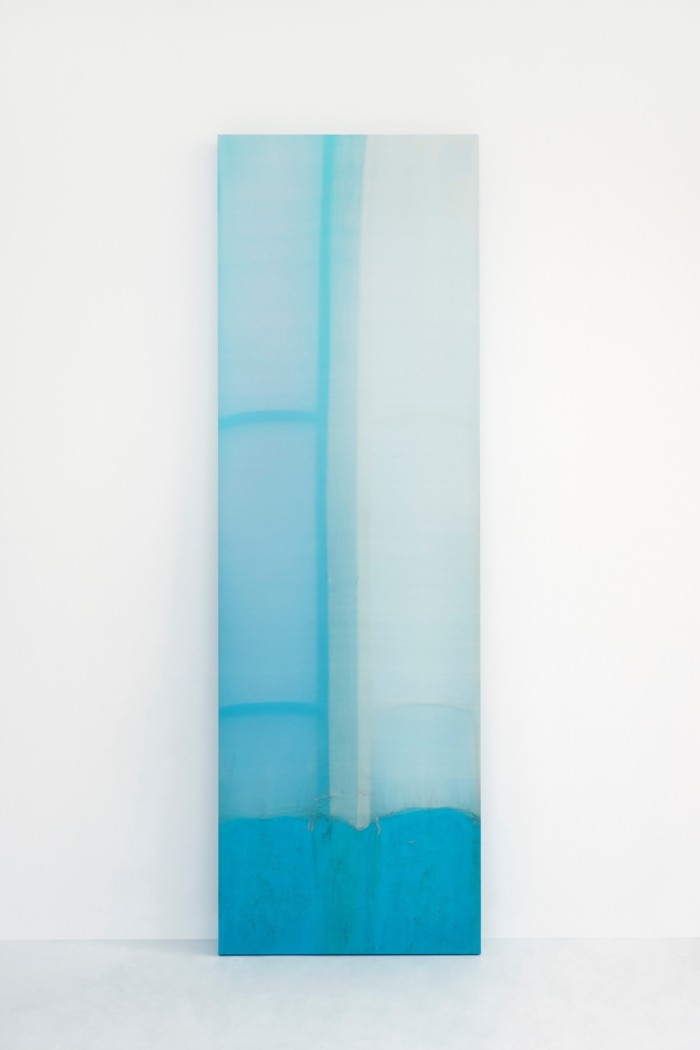

“I’m committed to showing exceptional work that deserves a platform, with an emphasis on artists who conceptually or aesthetically create their own way,” says Traore. She cites the work of New York-based artist James Perkins, whose “post-totem” pieces — silk structures exposed to the elements and then restretched as paintings — were on display at the gallery in the summer of 2022. Most recently, the gallery exhibited an installation of prints by Cheyenne-Arapaho artist Hock E Aye Vi Edgar Heap of Birds and tapestries incorporating human hair by Welsh-Ghanaian artist Anya Paintsil.

In today’s climate, art institutions often expect artists of colour to make work that explicitly addresses race and identity. Traore wants that engagement to be an option, but not a constraint, for the artists whose work her gallery shows. Performative allyship and tokenisation in the art world have been a constant source of frustration; she has built her programme in opposition to such mindsets. For her, that means showing less readily legible abstract work alongside figurative work depicting black subjects.

Last year, Hannah Traore Gallery participated in 1-54, an art fair dedicated to contemporary art from Africa and the African diaspora, with a display of photographs by Jamaican-American artist Renee Cox. For its second fair, the gallery is showing in Frieze LA’s Focus section, which features galleries under the age of 12. Previously devoted to Los Angeles spaces, this edition of Focus is also highlighting galleries from Minneapolis, New York and Chicago.

Traore knew right away that she wanted to mount a booth pairing work by Falquez and Garrison-Msingwana. “I’m interested in how both artists deal with drapery,” she says. “In art history, drapery indicates wealth or royalty or divinity. Who is depicting drapery and who is depicted with drapery? Camila and Moya are flipping the script in different ways.”

Falquez grew up in Barcelona, moved to New York aged 21 to pursue photography and soon garnered attention for commercial work for clients such as Nike and Hermès. At Frieze Los Angeles she will be showing five portraits taken in New York, Cuba and Puerto Rico. “My subjects are people who are often historically overlooked,” says Falquez. “What does it look like when we place them at the centre of these ideas of power and dignity?” The artist describes herself as a “painter with fabric”; her sitters don elaborate couture constructions that she makes using fabric, clamps and tape.

Garrison-Msingwana will present five canvases from his LAUNDRY series. Begun in 2017-18, the series revolves around what the artist has termed PILES, human bodies so intertwined with fabrics that the clothing itself seems alive. He is interested in the ways in which fashion interacts with the architecture of bodies, as well as the sociological role that clothing can play; textures, patterns and symbols integrated into each PILE become indicators of identity.

Clothing will likewise be at the heart of a concurrent exhibition at Traore’s Manhattan gallery space. The group show, opening during New York Fashion Week, revolves around an archival shirt by Helmut Lang; Traore is giving over the space to critic and curator Antwaun Sargent, who is organising the exhibition for the brand. Eager to see more instances of fashion and design entering gallery spaces, Traore is also planning a future collaboration between an artist and a fashion designer.

“I hope to encourage other galleries to be open-minded about what they show and, between that and building a space devoted to artists, make a permanent mark,” says Traore.

Comments