Plastic recycling: green necessity or waste of effort?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

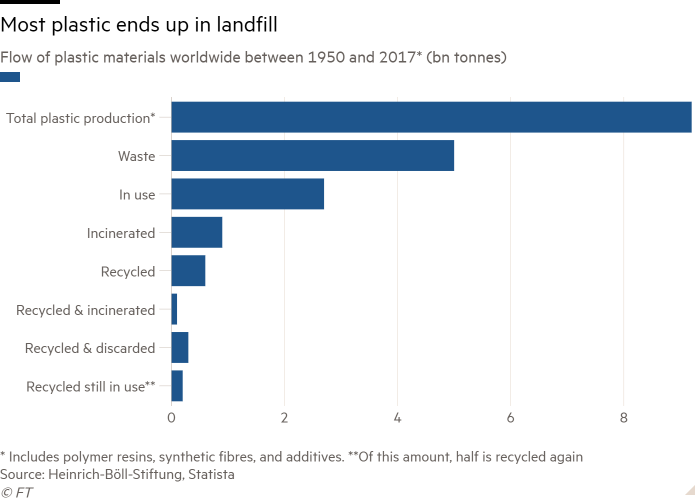

Since the 1950s, some 9bn tonnes of plastic have been produced globally. About half of that was made in the past 20 years. Around the world, one million plastic bottles are purchased every minute. Plastic clogs our oceans and our veins: scientists have detected it in the deepest part of the Pacific and, this year, in blood samples from the general public.

Much of this plastic is single-use: burger wrappers, coffee cups, drinks bottles — chucked away after a one-off indulgence. The majority of it is dumped in landfill or lost in the environment, where it may take centuries to decompose. According to the UN, only about 10 per cent has ever been recycled.

Yet companies and consumers continue to look to recycling as a way to ease the plastic problem. A string of consumer goods giants have publicly committed to making more of their products and packaging from recycled materials.

Coca-Cola has pledged to use recycled material for 25 per cent of its packaging by 2030. Unilever aims to cut its use of virgin plastic in half by 2025. McDonald’s plans to make all of its packaging from recycled or renewable sources by 2025. And so on. Polls consistently suggest the public also like recycling: it makes them feel that they are doing their bit.

However, this confidence masks a complex web of issues around plastic recycling. Recycling rates remain abysmally low and critics argue that we should look at alternative ways to tackle plastic pollution.

A number of factors contribute to low recycling rates: consumer confusion over what can be recycled; a lack of standardisation, with different waste companies processing different plastics; and a fluctuating market that makes much of the waste unprofitable to recycle.

In the US, there are almost 10,000 recycling companies, each with its own criteria for what plastic it can manage. Likewise, in the UK, a BBC analysis found 39 sets of local authority rules for recycling. Consumers are mostly unaware of this.

“There are hundreds of different plastics,” explains Judith Enck, president of Beyond Plastics, a US campaign group with a mission to end single-use plastic. “Each plastic has different toxic additives and different colourants. That’s why plastics have never achieved a high rate of recycling and never will.”

While many plastics have the potential to be recycled, most are not because the process is costly, complicated and the resulting product of a lower quality than the original. Despite rising demand for recycled plastic, few waste companies turn a profit. Part of this is because virgin plastic — pegged to oil prices — is often cheaper than recycled plastic, meaning there is little economic incentive to use it.

Steve Alexander, chair of North American industry body The Association of Plastic Recyclers, says the industry could solve all its other challenges if it had a stable supply of waste. “Recyclers have ample capacity to recycle as much material as necessary,” he says. “We can solve the design issue, the sortation issue, the processing issue, the end-market issue. What we can’t solve on our own without government intervention is the supply issue. We need more material. It’s as simple as that.

“If programmes collected the same material, and consumers understood what to put into the stream, over time you’d have market certainty, and the price would come down.”

Yet much of our plastic waste is difficult to recycle. Lightweight food packaging, like a mozzarella packet, contains different plastics, dyes and toxic additives. This dirty mix means plastic recycled through mechanical methods — the most common form — can only be melted down and moulded anew a couple of times before it becomes too brittle to be reused. And the nature of the process — requiring collection, energy and industry — means plastic recycling has a carbon footprint of its own.

Matthew Jones, professor of inorganic chemistry at the University of Bath, believes a combination of mechanical recycling and chemical recycling could be a solution. They complement each other, he says: “You need both processes and you need to weigh up the pros and cons for each, for each different plastic.”

Chemical recycling — where catalysts break plastic down into its constituent parts to be remade — is attracting growing interest and investment. Petrochemical giants including Chevron and Dow Chemical have established partnerships with start-ups to harness technology to turn plastic waste into oil or gas. Shell and ExxonMobil are building outfits to upgrade plastic waste.

But critics say fossil fuel companies pursuing plastic production as a new growth area is merely exacerbating a problem that those same businesses helped create.

Though promising, chemical recycling is also decades from widespread commercialisation. It is unable to deal with all types of plastic and can require too much energy to make it economical.

Given all of these difficulties, environmental groups say recycling is not the solution — and argue that creating more products from recycled material to attract environmentally conscious consumers merely aggravates the plastic problem.

“The solution is to use less plastic and for the plastic industry to stop misleading the public about the recyclability of plastics,” says Enck. “They should stop making false claims about the recyclability of plastics since they know most will either be littered or landfilled or incinerated.

“Using less plastics means shifting to reusable products and relying more on paper, cardboard, glass and metal — all of which should be made from recycled content.”

This may require policymakers to find ways to change consumer behaviour through education and incentives, such as the “reverse vending” that is widespread in Scandinavian countries: customers receive cash or coupons for depositing used bottles in a return vending machine.

Other interventions could include regulation to standardise packaging and collection, and to phase out single-use plastics altogether.

But Alexander insists that dismissing recycling entirely is neither desirable nor practicable. “If you want plastics to be sustainable, recycling must be at the basis of anything else you do with a plastic product,” he suggests. “We will always have some form of plastic packaging, so you must have a recycling system that can make that sustainable.”

The potential to create a circular plastic economy does exist, he says, but depends on action at all levels, along with innovations to ensure plastic is reusable, recyclable or compostable: “It requires a massive overhaul and collaboration between manufacturers, supermarkets, industry giants, governments, consumers — the likes of which we are not even close to witnessing.”

Comments