Lipsticks, lattes . . . and now labradors: JAB’s bet on pets

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

After spending more than $50bn on coffee chains, restaurant groups and cosmetics companies, JAB Holdings has found a cute solution to boosting its mixed returns.

The European group, which manages money for Germany’s billionaire Reimann family and outside investors, is hoping that pets can outperform its previous investments in a tougher economic climate.

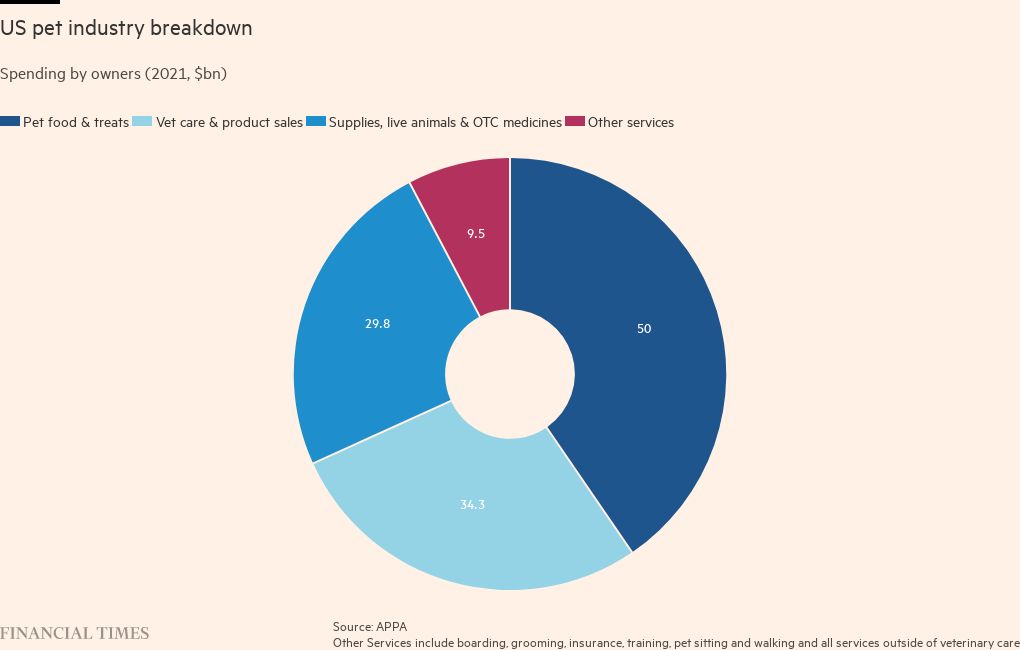

Over the past four years, JAB has spent more than $9bn on acquisitions to become one of the world’s largest operators of veterinary practices and invested more than $2bn to acquire pet insurance companies that will cover more than 2mn pets next year.

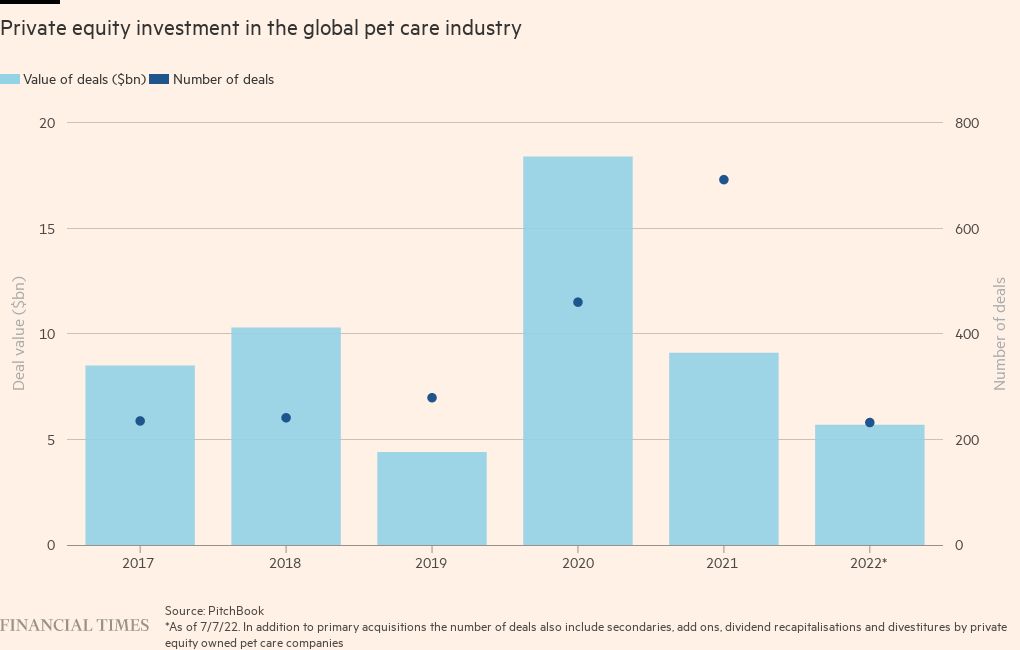

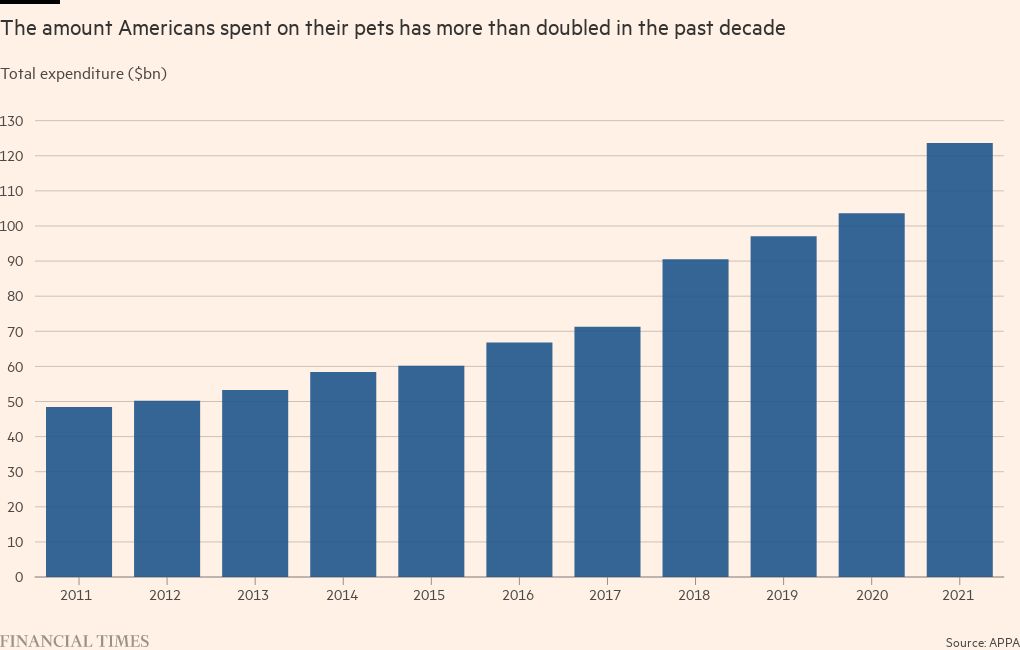

With pet ownership surging during the coronavirus pandemic, the sector looks more reliable for JAB than lipsticks or lattes. But regulators are becoming concerned about the pace of acquisition and subjecting JAB to ever-closer scrutiny.

The US Federal Trade Commission last month ordered JAB to divest vet clinics twice in less than a month, alleging that two proposed transactions could have created monopolies. The antitrust regulator told JAB to sell 11 clinics before completing the purchases of Sage Veterinary Partners for $1.1bn and Ethos Veterinary Health for $1.65bn.

The JAB measures are “part of our actions to heighten our scrutiny of private equity-driven merger activity”, an FTC official told the Financial Times. “We’re hoping it will have somewhat of a deterrent effect.”

At first glance, JAB is an unusual target of the FTC’s tougher stance on private equity.

The group’s roots trace back to the 1820s in Pforzheim, Germany, as a chemicals and industrial business. In 1981, former management consultant Peter Harf was hired by the Reimanns to revitalise the family-held company and build a broader business empire.

After listing on public markets and merging with Reckitt & Colman in 1999, Harf, over the past decade, has transformed JAB from a family office into a diversified holding company, which also manages $17bn on behalf of endowments and sovereign wealth funds.

“We are not the typical private equity firm,” said Joachim Creus, a managing partner at JAB. “We are not there to buy an asset, cut costs and then sell it a few years later. We are really an evergreen investor with a significant amount of permanent capital.”

JAB initially cobbled together small publicly traded and independent coffee roasters into a portfolio that now sells more coffee than Starbucks. It expanded into restaurants and beverages with its $7.5bn purchase of Panera Bread in 2017 and Dr Pepper a year later for $18.7bn.

Before the pandemic, it began forming a theory that the model could be applied to pet care.

Olivier Goudet, JAB’s chief executive, was hired in 2012 from Mars, the consumer goods giant, which has large pet care operations. In 2019, JAB sparked a legal battle after it poached Jacek Szarzynski, a Mars finance executive, soon after Mars’ $7bn takeover of animal hospital chain VCA.

Pet care attracted JAB because of the increase in ownership in the US and the “humanisation” of domestic animals. Owners do not treat vet visits as an optional purchase, JAB believes, and yet fewer than 3 per cent of them buy insurance coverage.

“The love of pets and the importance of pets will continue to be important no matter what the economic environment is,” said David Bell, a senior partner at JAB who helps oversee the firm’s pet investments.

Mars’s takeover of VCA also underscored the ability to quickly build scale. Private buyers including midsized buyout funds have for decades consolidated individual vet clinics into regional pools. It gave JAB the ability to build a broad platform with just a few acquisitions.

JAB’s first two deals, Compassion First and NVA, were both private equity roll-ups. When merged, it instantly made JAB one of the largest players in the industry with 1,500 practices, from which it could expand into higher-margin specialised pet healthcare services. The firm’s most recent funds have focused their investment exclusively on pet care.

The push has come as JAB has accepted that its initial wave of acquisitions in consumer goods has not achieved its initial targets.

“Our internal yardstick is to generate a long-term absolute compounded total shareholder return of 15 per cent for our entire evergreen vehicle, regardless of economic cycles,” JAB told its investors in March. “As such there is nowhere to hide . . . ”

Coty, its perfume and cosmetics platform, has struggled amid quickly changing consumer spending habits. “The company has clearly been our well-documented and commented ‘problem-child’,” JAB said in the letter.

Earlier this month, Panera Brands, its portfolio of restaurant assets, terminated a deal to go public amid a broad market sell-off. JAB also was forced to recapitalise Pret A Manger during the pandemic.

One bright spot has been its takeover of Dr Pepper. The investment by JAB and its investors has doubled in value, according to documents.

Pet care, though, has been its big outperformer. “Our initial returns have been well above our expectations,” JAB told its investors in March. “[B]ut we do not count our chickens yet as we are only in the first quarter of the game.”

Vet centres remain ripe terrain for consolidation, with many top dealmakers closely watching the FTC’s increased hostility.

“Most veterinarian businesses are small practices run by vets who are essentially doctors who love pets. They are typically not world-class business operators,” said one rival private equity executive, who noted that family-run practices often had succession issues if the next generation chose another career.

“If I can get some liquidity and sell it to someone who rolls it up and does the stuff I hate like paperwork and customer acquisition, it is awesome,” said the executive. “They will eventually all be rolled up, as was in the case with dental practices and doctors’ offices.”

A hospital director at a US veterinary clinic owned by JAB said having a corporate owner had made the facility less nimble. “If tomorrow I decide I want to build [a new hospital], it’s no longer a three- or four-person decision. It’s a 40-person decision,” the director said.

But the ownership also came with stronger financial backing that allowed the clinic to “think futuristically a little bit more” and no longer “make every decision with money in mind”, the director said. Benefits also included centralised legal or human resources departments.

Veterinary businesses carry less risk than traditional healthcare investments, which have attracted heavy private equity investment, often with terrible results. “From a legal perspective, there is a low reimbursement risk,” said Christopher Atkinson, co-chair of the M&A and private equity practice at law firm Katten.

Moreover, private equity investors including Sweden’s EQT believe the sector is highly resilient to a downturn. One prominent firm has uncovered data from the 2008 financial crisis that indicated pet owners prioritised spending on their pets’ health over their own prescriptions.

Private equity’s push into veterinary care has come under criticism for pushing profits over customers. A firm owned by one of JAB’s rivals jacked up the price of medication by 78 per cent in one case after it took over, one vet told the FT.

The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority has investigated two acquisitions in the sector this year, signalling growing scrutiny in Europe of veterinary care consolidation.

In the US, JAB must now seek the FTC’s approval before acquiring a veterinary clinic within 25 miles of a JAB-owned facility in five states and the District of Columbia. JAB must also notify the regulator 30 days ahead of buying a clinic within the same range anywhere in the US. The measures — which will last for 10 years — are unprecedented for a private equity-backed deal, according to the FTC official.

Two Republican FTC commissioners characterised the manoeuvre as over-reach, though the agency’s Democratic-appointed chair Lina Khan said it was “warranted” because of JAB’s previous business practices. These types of orders would “allow the FTC to better address stealth roll-ups by private equity firms like JAB/NVA and serial acquisitions by other corporations”, added Khan.

Drew Maloney, head of the American Investment Council, a lobbyist for the private equity industry, said: “[I]t is concerning that the FTC appears to be targeting private equity because of who they are rather than what they have done.”

JAB, though, cannot afford to fall out with the FTC as it has more pet deals to do. Just last week, it announced two acquisitions of European pet insurance businesses. Last month, it also invested $1.4bn to acquire a large pet insurer from Fairfax Financial Holdings.

“The dialogue and the discussion with the FTC was fully anticipated,” said JAB’s Bell, who added he was “grateful” for the regulator’s work. “The end result was in line with what we anticipated.”

Comments