Goldman arm offers latest route into private equity investing

Simply sign up to the Private equity myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When the pioneers of modern private equity, Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts, raised $30m for their first buyout fund in 1978, the money came from a tight circle of backers.

In the decades since, as KKR and its private equity peers have grown into behemoths with trillions of dollars under management, the industry has never quite shaken off its reputation as the preserve of institutions and the ultra rich, where sophisticated investors can find far higher returns than those available to the average saver.

More recently, however, private equity has become steadily more accessible as leading managers such as Blackstone, KKR, Carlyle, Apollo and Ares have gone public, and new investment vehicles opened the door for individual investors to share in private equity’s alluring returns.

Retail investors will soon gain another entry point into private capital, as Goldman Sachs’s Petershill Partners, which owns minority stakes in a range of alternative asset managers with a combined $187bn of assets under management, has announced plans for an initial public offering in London.

But, at a time when the shares in major listed private capital managers have tripled in value since the depths of Covid-19 and the pandemic has heralded a frenzy of high-priced deal making, what should self-directed investors consider before jumping into private equity?

“I think the markets are frothy at the moment,” said Claire Madden, managing partner at London-based alternative investment firm Connection Capital. She cautioned that companies may try to capitalise on the buoyant market. “Private equity managers . . . will see that the markets are paying premium prices,” she said.

However, timing the market should not be top of mind for investors who are thinking about taking the plunge into private equity, according to experts. Investors should be prepared to buy and hold for the long term, since the value of private equity deals takes years to accrue.

“This is not something that, as an investor, you should be looking to trade in and out of,” said Madden.

While some believe all investors should consider a small allocation to private markets — to diversify their portfolios and fire up returns — others argue that the long time horizons and complexities involved make the sector better suited to wealthy investors than retail players.

“This is really a product for millionaires and multimillionaires, whereas before it was a product for people who had hundreds of millions or billions,” said Alex Davies, founder of Wealth Club, an investment service that helps wealthy clients select private investments.

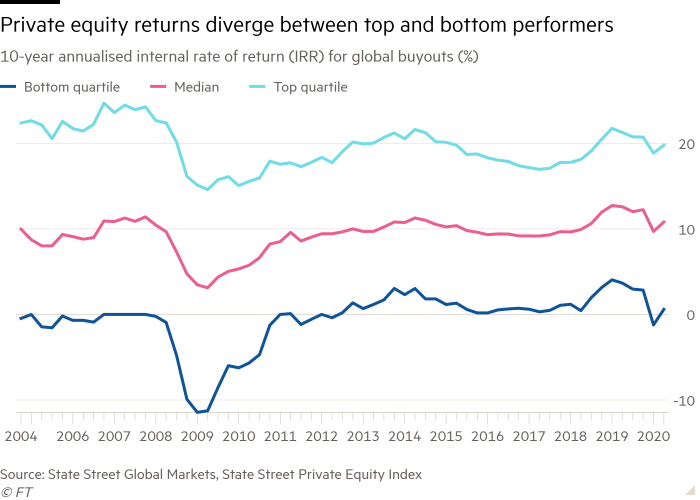

Part of the attraction comes from private equity’s reputation for strong performance, but returns vary across the sector. The top quartile of global buyouts has returned a handsome 20 per cent on an annualised basis over the past 10 years, according to State Street. Meanwhile, the sector’s bottom quartile has limped along, with returns close to zero.

“There’s a lot of managers that are very average, I think,” said Mick Gilligan, head of fund research at wealth manager Killik and Co.

At the same time, competition among managers is heating up. Private equity firms have struck more deals in the UK in the first half of the year than in the same period in any year on record, and many firms are still raising money faster than they can spend it. The private capital industry has more than tripled its assets to $7tn over the past decade, according to Morgan Stanley.

“There’s much more demand at the moment than supply in terms of available investment opportunity,” said Jeffrey Sacks, Europe head of investment strategy at Citi Private Bank.

Investors also need to choose how they want to access the sector, as the range of options has proliferated. The main route for ordinary investors is via the stock market, where a number of investment trusts, ETFs and listed companies provide different types of exposure.

Some vehicles back a particular private equity fund, while others diversify in a “fund of funds” that itself invests in a portfolio of buyout groups. Another option is to buy shares in the listed private equity manager itself, which allows investors to get exposure to its fee revenues.

The return from managers is based primarily on their ability to keep growing their pile of assets, on which they charge lucrative management fees to institutional investors such as pension funds. They also receive a share of the profits from successful funds, known as “carried interest”, typically 20 per cent.

Petershill’s planned IPO will offer yet another structure. The company owns stakes in 19 global alternative asset managers, including private equity but also private credit, hedge funds and real estate, making it a diversified option. A public listing could value the portfolio’s assets at more than $5bn. Part of the appeal for investors is that it is a bet on Goldman Sachs’s skill at accessing the best deals and picking the best-performing managers.

Investors also need to be attentive to costs and the level of transparency about who reaps the rewards for good performance. Bridgepoint, which this summer became the first private equity firm to list on the London Stock Exchange since 1994, has drawn criticism for not disclosing the amount of money its executives receive from “carried interest” payments.

Buying into structures like funds of funds can also mean paying multiple layers of fees, in a sector sometime criticised for high charges. In a paper last year, Oxford academic Ludovic Phalippou estimated that “private equity funds have returned about the same as public equity indices since at least 2006,” while collecting $230bn in performance fees.

While investors weigh costs against the promise of performance, they are under more pressure to put money into private markets, as fewer companies choose to go public.

Peter von Lehe, lead manager of NB Private Equity Partners, said: “Because private equity owns a larger number of companies today than it did 20 years ago, if retail investors don’t have access to invest into private equity, the universe of investible companies for retail investors has shrunk.”

Comments