‘We’ve been screaming’: the makers of Dopesick on reframing the opioid crisis

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At the very start of the drama Dopesick, we hear the fictionalised voice of the pharmaceutical billionaire Richard Sackler. “The time has come to redefine the nature of pain,” says Sackler, played by Michael Stuhlbarg. He says America has created “an epidemic of suffering”, whose victims are “not even living at all”. His solution is a pill for long-term pain: OxyContin.

It’s a chilling sequence, because the audience knows that Sackler did redefine pain — by multiplying it. Instead of alleviating an epidemic, he helped to create a new one based on opioid addiction. More than 500,000 of its victims have died from overdoses.

After more than three decades, the scale of the opioid epidemic still defies artistic depiction. There have been Pulitzer-winning news reports and Emmy-nominated documentaries, including one by the Financial Times and PBS. Each must wrestle with Stalin’s alleged dictum that one death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic.

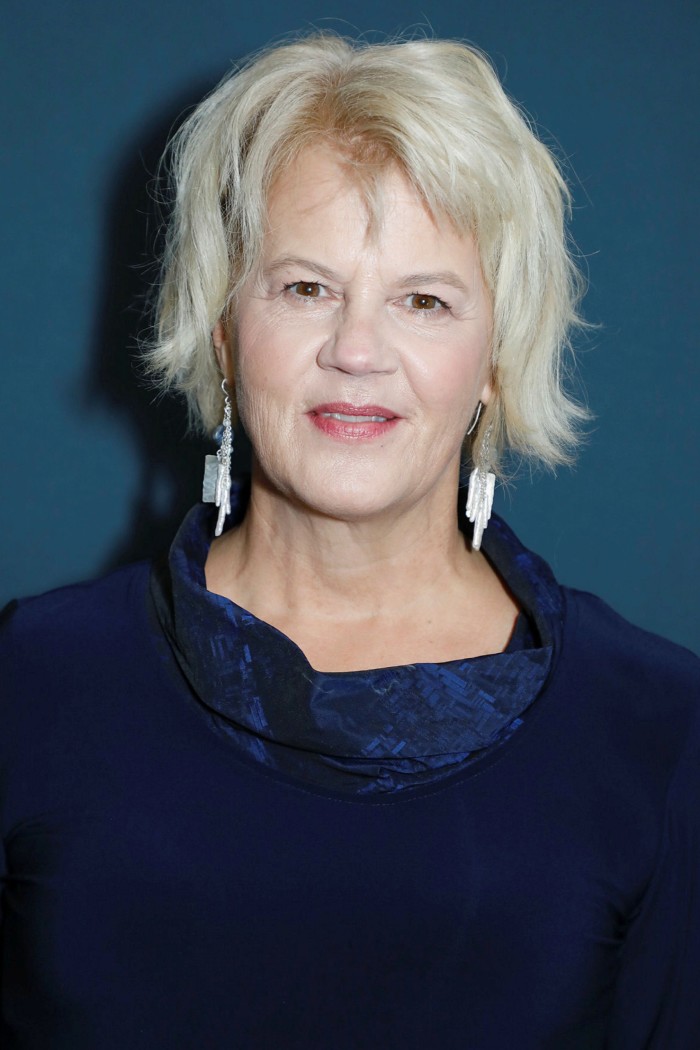

“All of the journalists — myself, Patrick Radden Keefe, Gerald Posner, Barry Meier — we’ve been screaming, waving the flag, about this for so many years,” says Beth Macy, a journalist whose 2018 book Dopesick formed the basis for Danny Strong’s mini-series. “Part of it is: it’s a very slow story. As the comedian John Oliver said, ‘If you want to do something evil, put it inside something boring.’”

In HBO’s Mare of Easttown, opioids are the backdrop for other crimes. In Dopesick, they are front and centre. The show finds suspense by following two prosecutors’ efforts to bring a case against the Sacklers’ Purdue Pharma in the face of multiple obstacles. “My client should be given a Nobel Prize, not a subpoena,” says a Purdue lawyer at one point.

In one corner is Richard Sackler, portrayed as a robotic, miserable figure, desperate for profit but also convinced that his opioids could be as beneficial as penicillin. In the other corner are Appalachian families, often driven to opioids by grinding work in coal mines. In the middle is a conscientious but persuadable doctor played by Michael Keaton, who took the role after his own nephew died from an overdose of heroin and opioids.

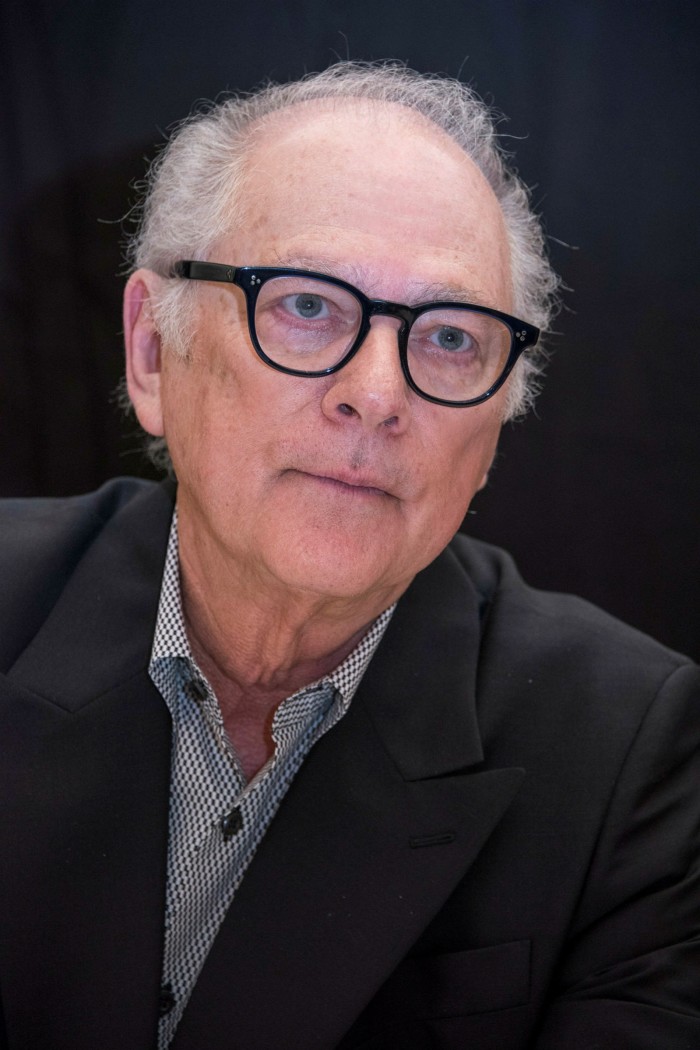

Dopesick is named after the physical agony experienced by opioid users when they run out of drugs. Its first two episodes are directed by Barry Levinson, whose previous takes on America’s dysfunction — such as Good Morning, Vietnam and Wag the Dog — have often managed a humorous side. In Dopesick, even he found the grey inescapable. “Look, I’m somewhat cynical about a lot of things,” he says. “But I am surprised by the infinite inefficiency and how much private money has gotten into government, that affects government.”

Purdue was allowed to market OxyContin as largely non-addictive. It could then cajole doctors into prescribing ever higher doses. Dopesick draws a contrast with Germany, which largely avoided an opioid crisis. “The Germans don’t believe in opioids, they believe suffering is part of healing,” as one Purdue character puts it.

So Dopesick’s narrative becomes a broadside not just against the Sacklers, but against power in the US: the weak regulatory agencies, the politicised justice system, the pervasive lobbying. Levinson, who has “problems with all the political parties”, hints at a wider sense of national decline.

“When I came to Los Angeles as a young man wondering what to do with my life, I never saw a homeless person. Now you see it to such a degree that you go: what happened? What is wrong here in our system that we can’t take care of certain things that we did take care of?”

Those who follow the news will know the opioid crisis has never been dealt with satisfactorily. Purdue Pharma was forced into bankruptcy, some museums dissociated themselves from Sackler philanthropy. But those members of the Sackler family who were involved in the OxyContin scandal have not faced criminal prosecution and retain much of their wealth.

“They’re going to give up $4.5bn [in one legal settlement], but they get nine years to do it. Most investing experts say they’ll be richer than they are right now,” says Macy. “That really isn’t justice, when you consider that the guy you used to work with at Subway who was arrested for dealing a user amount [of illegal drugs] is still in jail.”

Today, in communities hit by opioids, employers are hiring, but “they can’t get enough employees to pass a drug test. These are the communities that Purdue targeted,” says Macy. “We talk about infrastructure, but first we need to build up our human infrastructure. We need to offer treatment, education, social support for these folks.”

Macy criticises Hillbilly Elegy, the best-selling memoir of JD Vance, now a Republican politician in Ohio, which she says “consistently blames the people of Appalachia for their own problems”. As a drama, Dopesick wants to show the Sacklers and the opioid victims as rounded characters, not cardboard villains and victims. Its conclusion is nonetheless clear — many opioid victims became addicted through no fault of their own, after their job prospects were shaped by a globalisation that was no fault of their own.

Dopesick will not jail the Sacklers, but it is a trial in the court of public opinion. Macy hopes that “the average American viewer” will stop blaming opioid addicts for their condition. That is “Richard Sackler’s playbook”.

‘Dopesick’ is on Hulu in the US now, and on Disney Plus in the UK from November 12

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Comments