Mariana Mazzucato on making waves as an economist — and in the pool

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Mariana Mazzucato, it appears, finds it hard to see something amiss without trying to fix it. Within minutes of meeting, she is tussling with the base of the wobbly table we are sitting at, while excoriating Britain’s low standards in handwriting (execrable) and swimming lessons (“I taught my kids how to swim, and their friends”). Around us, in the reception of the Pancras Square leisure centre, is the bustle of visitors to its pool and gym and to the council offices above it.

The Italian-American economist spends most of her time tackling rather bigger problems — chief among them, the failings of mainstream economics teaching and modern capitalism. While other voices in this debate have focused on inequality, Mazzucato, a professor at UCL, wants to expose what she sees as a more fundamental set of misconceptions, about the meaning of economic value. “Philosophers have been talking about the public value since the time of Aristotle but in economics we talk about the public good — and this is a much more static concept,” she says.

In particular, she wants to challenge the pervasive view that innovation happens in the private sector, with government’s role limited to redistribution, levelling the playing field and fixing market failures. In fact, she argues, many private-sector actors — from finance to Big Pharma — are extracting or destroying value created by others. Meanwhile, the public sector can and should be a co-creator of wealth that actively steers growth to meet its goals — be they green energy, care of ageing societies or giving citizens a share in the digital economy.

This is a message that politicians can embrace and Mazzucato’s advice is in demand from governments across the world. Her latest book, The Value of Everything , is receiving accolades on Twitter from finance ministers and student idealists alike, and is clearly set to be essential summer reading for civil servants.

All this makes for a punishing schedule. Our conversation is punctuated by yawns, the result (or so she assures me) of a late dinner with her publisher. In a few days, she is flying to Rwanda for a forum on governance; the week after that, to Brazil. The grey coat she is wearing was an impulse purchase on a work trip to Shanghai.

“I’m at home a lot when I am around. I travel every couple of weeks but, otherwise, I’m always back in the evenings — it’s a very Italian kind of thing, having a proper dinner together,” says Mazzucato. Her husband Carlo Cresto-Dina, an Italian film producer, travels as well (he has a film selected for competition at this year’s Cannes festival) but, “between us, there is always someone home”. Even so, between four children, building up a new department at work and her itinerant public policy brief, she admits — with an element of deliberate understatement — “it can get hectic”. She has invited me here to show me how she unwinds.

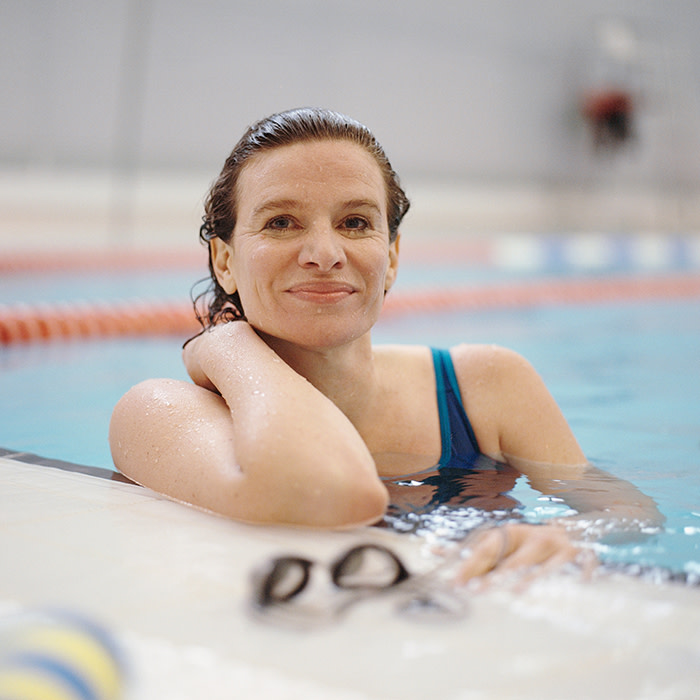

“I’ve never had therapy. I’m not a yoga type of person.” (This too, is an understatement — I have never met anyone who seems less inclined to introspection, let alone staying still long enough to hold a yoga pose.) “I swim. I always make a joke with my friends that I jump in as Cruella de Vil and I jump out as Mary Poppins — in terms of being a good mother. I get home and I’m calm if I’ve swum.” Swimming works, she adds, because it forces her to breathe — an explanation that makes sense after an hour trying to keep up with her quick-fire conversation. “My mother, when we talk on the phone, will always say — in Italian — ‘Mariana, are you breathing?’”

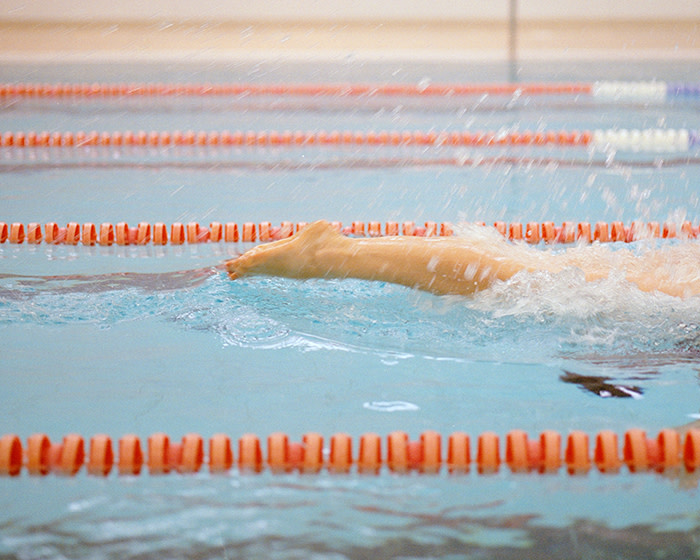

Mazzucato has a swimmer’s physique, and is at home in the water. She jokes that as an overworked, almost-50-year-old, she is in just the demographic to succumb to a heart attack on contact with cold water. But she pushes off at a cruising speed considerably faster than my own, and completes a couple of lengths of competent butterfly — the legacy of long childhood summers and training at a swim club while growing up in New Jersey, where her father is a researcher in plasma physics at Princeton.

The pool is a cut above the average public baths — with a backlit wall, water jets and a bubble pool — but Mazzucato usually swims on Hampstead Heath. She is one of the year-round regulars at the lido and ladies’ pond, albeit one of the few to make the concession to English winters of wearing a wetsuit.

We are at the Pancras pool partly for convenience — it lies neatly between her north London home and UCL, where she took up post in October to set up a new Institute of Innovation and Public Purpose. A second reason is that both the leisure centre and the King’s Cross redevelopment in which it stands serve as a case study in public-private collaboration. The pool is run by GLL, a social enterprise that has taken over many community centres previously run by local authorities. Upstairs, a public library and café sit alongside Camden’s council offices.

Close by is Granary Square, a popular spot with children, who splash in the fountains on sunny days — but while it serves as a public space, it is privately owned and patrolled by security guards. Mazzucato has nothing against the principle of private companies delivering public services, if appropriate conditions are set. But she does not approve of this blurring of boundaries, arguing that “it’s useful to know explicitly” whether a place or service is publicly run, or privately owned and merely open to the public, or somewhere in between the two. If I understand her correctly, this is partly because greater clarity should lead governments to think more carefully about the terms on which they bring in the private sector. “If there is a public subsidy, there should be deals struck and conditions attached.” But it would also lead to a more accurate appreciation of the value governments create. “I think the public sector should be more of a serious partner, with ambition and confidence to strike healthy deals, but also to co-create and co-shape markets, not just to fix them.”

She thinks civil servants in Britain have fallen prey to the narrative so often adopted by industry lobbyists, “that they shouldn’t take too many risks, they shouldn’t pick winners” — and that the result is a haemorrhaging of talent from the public sector and an unquestioning acceptance of the lobbyists’ mantra that low taxes and regulation are needed to attract investors and entrepreneurs.

“In the US, they talk Jefferson but they act Hamilton,” she says. “Here they talk and act Jefferson.” (Thomas Jefferson’ wrote that he was “not a friend to a very energetic government”, whereas his great rival insisted the US should pursue an activist industrial policy.) This despite the success of projects such as the Government Digital Service — where civil servants, rather than the usual IT contractors, not only created a website that genuinely met citizens’ needs, but, she says, “also made it a really, really cool place to work, so the Tech City guys were having a hard time hiring.”

Mazzucato has been making these arguments for a long time. In her 2013 book, The Entrepreneurial State — written in response to post-crisis austerity policies — she sought to demonstrate the extent to which Silicon Valley’s success was founded on state-funded research, with government agencies playing a similarly critical role in many other economies. The new work aims to give her ideas theoretical underpinning. A long section duly discusses the ways in which different schools of economists approached the idea of value over the centuries, before the view took hold that prices are set by supply and demand and “value is in the eye of the beholder”.

Simply to question this assumption, she claims, is a heresy that will annoy “all the economics departments who think it’s OK to teach one theory of value — the neoclassical theory — and apply it to everything”. She did her own PhD at the New School for Social Research in New York precisely because of its pluralist ethos; it taught alternative models, she says — Keynesians, Marxians, Neo-Keynesians and classical economists, as well as neoclassical.

Mazzucato has described her role as “disrupting economics” but in the pool, she is causing a different kind of disruption, upsetting a swimmer who had been breast-stroking in the intermediates’ lane until the interruption of her backflips and a camera crew. He remonstrates mildly — then pauses and realises that he not only knows Mazzucato but has been round for dinner at her house. I suspect that any academics she riles on matters of economic theory must be similarly disarmed, whether won round by her Italian cooking or left spluttering by the dialectic equivalent of a mouthful of cold water.

Mazzucato’s main impact, though, has been in public policy. Although she is generally seen as left-leaning, she says she has no political agenda, and is ready to advise “those who will listen”. In the UK, her fingerprints are on both the Conservative government’s industrial strategy, published in November, and last year’s manifesto for the Labour party. Despite a dislike of nationalism “in all its forms”, she also has a formal role advising Nicola Sturgeon’s Scottish National Party, and claims partial credit for the Scottish government’s decision to set up a national investment bank.

But she says that “probably the highest impact thing I’ll ever write” was a strategy paper published in February, intended to guide the EU’s research and innovation programme. This sets out her idea that governments should seek to steer growth by articulating “missions” — with bold social aims and measurable targets — that will spark innovation across sectors. A precedent is the US quest to put a man on the moon. A current example might be to aim for 100 carbon-neutral cities by 2030.

Needless to say, Mazzucato has detractors — and not only among the fund managers and other self-styled wealth creators at the sharp end of her criticism. Perhaps their most powerful argument is that for all the good that governments do, they also get a lot wrong, whether through incompetence and wasteful spending or through outright capture and corruption. And while it is easy for ministers to talk the talk on missions, grand aims are of little use unless they are also willing to take politically tough decisions to achieve them.

“There are lots of wrong policies and wrong ways to run public institutions,” she counters. “But there’s nothing deterministic about it . . . Looking at the narratives used to justify certain choices, and debunking some of those narratives, is how I see my role. That’s especially important today.”

Her message on the virtues of the public sector does not prevent her appreciating occasional extravagance. With a touch of embarrassment, she admits the Pancras pool is not her usual spot for central London swimming. The spa at the St Pancras Hotel — housed in the red-brick Gothic edifice above London’s Eurostar terminal — is a more luxurious affair. It is only open to guests, but staff there yielded to persuasion and took her in as its sole regular member. It comes as no surprise to hear that they now know her well enough to make her a birthday cake.

Delphine Strauss is an FT economics correspondent

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments