The new Queen of Denmark – an interview

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

This weekend, following the abdication of Queen Margrethe II, Crown Prince Frederik and Crown Princess Mary will become the new King and Queen of Denmark. Here we republish our 2022 interview with Crown Princess Mary

Looking through an open door in Crown Princess Mary’s study at Frederik VIII’s Palace, the view to the adjacent salons is trippy: wild walls of colour and texture by artists such as Olafur Eliasson, Kaspar Bonnén and Morten Schelde. The works were commissioned by the princess and her husband, Crown Prince Frederik, in 2009, when they took over the building that bears his forefather’s name and invited 10 Danish artists to decorate its state rooms. The decor is a useful synthesis of modern (a daring scheme) and traditional (the walls retain their gilded mouldings and curly cornices frame every door). It’s an apt reflection of the couple’s progressive public persona, but certain formalities remain. A courtier instructs as to the correct greeting. “We wouldn’t do this,” she advises, demonstrating an elbow bump with a forbearing smile. I stick to a hands-free bow.

Her Royal Highness Crown Princess Mary of Denmark enters the study from her next-door office. She is dressed in black trousers and an emerald-green bishop-sleeve blouse with rigorous cuffs, her mahogany hair polished and pristine. She is warm but poised, ethereal but commanding, much like her surroundings. As the residence of the heirs to the Danish throne, the palace is a place of representation, and the princess well understands how her choices – of hairstyle, outfit or decorative scheme – will project. “A monarchy exists in the time and the society that it is a part of, and Danes are progressive and innovative and free-thinking,” she says. “How progress happens is dependent on the personalities of the people within the royal family, and, of course, the people they are among.”

As crown princess, Mary is the future queen of Denmark. Australian by birth, she married Queen Margrethe II’s eldest son in 2004, and has been a consistent figure on the world stage ever since. If an appetite for public service was instilled in the Crown Princess from an early age, it came from academic circles rather than a childhood filled with high-profile fundraisers and galas. Mary Elizabeth Donaldson was raised worlds away from the elite schools, sports or society mixers that have shaped many of her princess peers in other countries. She was born in Hobart, Tasmania, 10,000 miles from Copenhagen, in 1972. Her father is John Dalgleish Donaldson, an applied mathematics professor and Scottish fisherman’s son, who emigrated to Australia in 1963 with her late mother Henrietta, who was an executive assistant at the University of Tasmania. (Today, he is married to the English suspense novelist Susan Moody.)

Mary grew up immersed in outdoor sports. She got a BA in commerce and law and worked in advertising in Melbourne and Sydney but, after the sudden death of her mother, she quit and went backpacking around the world. She met Crown Prince Frederik, now 53, in a bar during the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Today, they live in the palace with their four children, Prince Christian, 16, Princess Isabella, 14, and the twins Prince Vincent and Princess Josephine, 11. In the vestibule next to the study, artist Jesper Christiansen’s Matrix-like world-map mural serves as testimony to the couple’s geographically diverse backgrounds.

If Australia is the new world, the Crown Princess couldn’t have found a greater contrast than Denmark, one of the oldest monarchies whose bloodline can be traced back to the 10th-century Viking, Gorm the Old. Since 1513, the kings of Denmark have alternated between the names Christian and Frederik. When her husband ascends to the throne, he will be the 10th Frederik to do so. Vestiges of formal tradition surround. A footman in white livery serves us coffee in white-fluted cups with bespoke gold rims from Royal Copenhagen. A neat stack of paper napkins carry the couple’s cypher, an interlocked F and M. Outside, bearskin-wearing royal guards have put their red overcoats on for the January rain. They’re marching along one of four identical buildings that form the octagonal Amalienborg Palace on the harbour of Copenhagen. Across the square is the winter residence of the 81-year-old Queen Margrethe II, the world’s third-longest reigning monarch after Queen Elizabeth II (her third cousin) and the Sultan of Brunei.

Growing up, the young Mary wasn’t what you’d call a royal-watcher. “I was very aware that Queen Elizabeth was our head of state and that we were part of the Commonwealth, but day to day I wouldn’t say there was a great deal of presence unless there was an official visit or a wedding or a jubilee,” she says, two big books on Queen Elizabeth now firmly placed on the sideboard in her study. “Today... wow. I can only admire Queen Elizabeth and my own mother-in-law, the Queen of Denmark, for their lifelong commitment and dedication to serving their country and their people.”

Her accent has taken on the flat intonation of Danish. She has mastered her adopted language and occasionally uses Danish words to express herself. When conversation switches to Danish, she uses the formal “you” – “De” rather than “du” – an elevated form of address sadly almost only observed by the royal family in present-day Denmark.

The Danish royal family holds no jurisdictional authority, but remains symbolically important for the country: a “samlingspunkt”, as the Crown Princess puts it, using a Danish term she translates as meaning “unifying body”. Her husband is a dedicated sportsman who leads an annual public “Royal Run” around Denmark, and looks dashing in a naval uniform. His mother, the Queen, is a larger-than-life personality: a multi-talented artist with a good sense of sarcasm, generous with herself but preserving an almost baroque understanding of duty, ceremony and protocol within her hyper-creative life. She’s incredibly popular. According to a 2020 survey by Kantar Gallup, 84 per cent of the country – population 5.8 million – support the monarchy.

“The monarchy is a unifying institution for the Kingdom of Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, which also comes with a bit of glamour, pomp and circumstance,” explains Helle Thorning-Schmidt, who served as prime minister of Denmark for the Social Democrats between 2011 and 2015 and is married to the Labour MP Stephen Kinnock. “Even in a welfare state devoted to equality, we appreciate a touch of grandeur.”

Maybe it’s the Hans Christian Andersen effect – the Little Mermaid statue is just down the marina from Amalienborg – but for all its social-democratic normality, Denmark doesn’t expect its heads of state to be just like you and me. The Queen presides over four palace residences, a hunting lodge, a château in France and a royal yacht, which is used for visits to the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Off-duty, the Crown Prince Couple guard their privacy. In 2009, when Oprah Winfrey was in Denmark filming a show, the media mogul confirmed to the Danish press that an interview request had been politely declined.

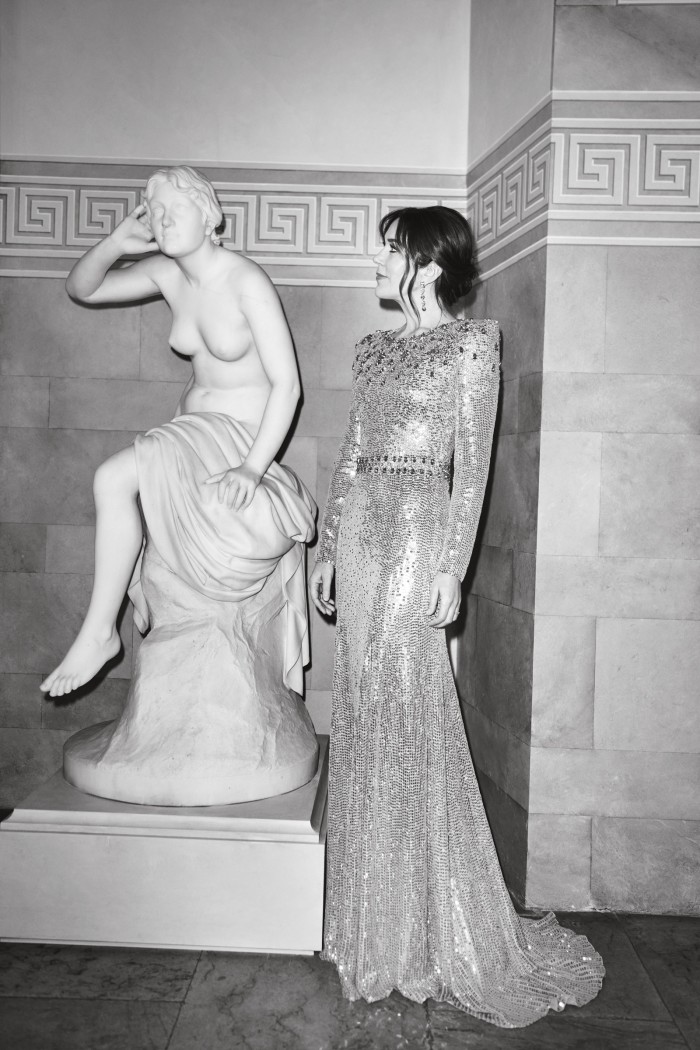

The glamour that surrounds the Crown Princess has hardly diminished the media’s interest. During the week of black-tie events that preceded her wedding, and which formally introduced her to the Danes, she had them floored: one resplendent ballgown after another, paired with the exquisite ruby parure originally worn by Désirée Clary (later Queen of Sweden and Norway) for Napoleon’s coronation in 1804.

“Very early on, it was clear that there were expectations about what you wore and how you dressed appropriately to an event,” says the Crown Princess who, for official duties, is now used to being bedecked in powder-blue moiré sashes, silver stars, white crosses and the diamond-encrusted Order of the Elephant badge. “That was pretty daunting for me. I was a T-shirt-and-shorts girl, known to go barefoot.” In subsequent years, she has demonstrated a decidedly modern approach to royal daywear, largely forgoing the territory’s skirt suits and dainty frocks for executive separates and streamlined silhouettes.

“As the future queen, Her Royal Highness’s ability to dress both appropriate to her standing but modern at the same time has always struck me as particularly impressive,” says Sir Paul Smith, a long-time friend of Crown Prince Frederik. “She has the confidence to dress with the authority her role requires but in a way that feels relevant today. She’s always dressed like a princess but never dressed up like one. She could make ripped jeans look regal!”

The Crown Princess isn’t afraid of wearing designers like Smith, either. Mary will casually mix Danish brands with Chanel, Prada and Hermès, and often wears young international designers such as Erdem too. “Her evening approach is not dissimilar to her approach during the day,” Erdem Moralioglu says. “There is something both regal and formal to her. She is absolutely appropriate for the event she is attending, and yet she always looks modern and beautifully relaxed.”

In 2010, when asked his thoughts on the Duchess of Cambridge, Karl Lagerfeld replied that Catherine, 10 years Mary’s junior and similarly lithe and polished, could be her “younger sister”. The comparison is inevitable: especially now when, like the Crown Princess, the Duchess is using her public platform to steer the press attention away from her wardrobe to focus on her other causes. “At times it can feel frustrating that what you’re wearing can overshadow the cause at hand,” says the Crown Princess. “But I’m sensing and hoping that there’s a shifting focus, that there’s less focus on the outer than there has been.”

Thirteen years ago, she participated in the first-ever Global Fashion Agenda, the Danish-led international sustainability summit, which has since become a frontrunner in the environmental conversation around fashion and boasted an extraordinary list of influential speakers. “Sustainability at that time was a relatively new focus,” she says of its success. “There’s been some progress, but an enormous transformation still has to occur. I look forward to the day that, when I buy a piece of clothing, sustainability is simply a gift with purchase.”

If it was fashion that first got her projected onto the world stage, recent years have seen her turning to more humanitarian work. The Crown Princess has become a powerful advocate for women’s reproductive rights, maternal health, sexual and reproductive rights in developing countries and international LGBTI+ rights. Some of her causes are obvious, others more controversial as far as the geopolitical landscape goes. “I exist in a time when, yes, these areas are still debatable and conflict-full, but it’s a human right,” she says of her decision to front the LGBTI+ organisation WorldPride. “I fundamentally believe that we all have the right to be who we are regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation. Denmark is a strong voice on this issue, and I wanted to lend my voice to the cause.”

Similarly, she has taken the lead in her work for women’s rights in developing countries. “I’ve always had a strong sense of justice: that everyone should have the same opportunities, no matter where you come from,” she says.

The Crown Princess has been a diligent student of her calling. In the two years before the pandemic, she undertook more than 20 working trips: she went to Kenya with the gender-equality organisation Women Deliver, to Indonesia with the United Nations Populations Fund and to Ethiopia with the Danish minister for development cooperation. A talented speaker, she delivered passionate speeches at human rights summits, and served as patron for the World Health Organisation. Last year, she went to Burkina Faso to raise awareness around the plight of women affected by issues like genital mutilation, forced marriage, underage pregnancy and education barriers. “Understanding that inequality and lack of respect for human rights were root causes for maternal mortality – that still today, a woman can risk losing life by giving birth – was where my journey started.”

On home turf, the Crown Princess has completed a military education for the Danish Home Guard in which she now holds the rank of captain, and she shares her husband’s affinity for sports. A keen equestrian, she has recently taken up dressage and has two horses, including a Danish warmblood, which she rides competitively. “It’s always been a happy place for me in the stables. It’s a place where I’m just Mary. It’s very meditative.”

Her favourite spots in Denmark are in nature. “I find the forests very exotic, especially in the spring when the beech trees come into leaf. The North Sea coast reminds me of Tasmania, both when it’s wild and when it’s calm.” In Copenhagen, it was always “Rosenborg Castle, with its fairytale renaissance architecture”, she says of the 1606 masterpiece that first captured her heart.

The Crown Princess has found affinities between Australia and Denmark, but does say that when she first arrived in Copenhagen, she sometimes felt she was too “direct”. “I searched forever to find the word ‘please’ in the Danish language,” she recalls, but the word doesn’t exist. Instead, her Australian candour has found an outlet in her causes.

“She has emerged as a very progressive representative for Denmark, which is something welcomed by many of us,” Thorning-Schmidt says. “We have always had an internationally minded royal family, but the Crown Princess has brought to the Danish monarchy a very resolute internationalism by immersing herself in work of a big-scale and global nature.” Thorning-Schmidt experienced “The Mary Effect” first-hand when she became CEO of Save the Children International. “She represents a small kingdom, and in that sense, she has to work harder to get noticed internationally. I’ve seen the international response to her on numerous occasions, and people really listen to what she has to say.”

Parallels to the People’s Princess are a given, but if Mary is the Danish Diana, it’s without the sombre subtext. The royal couple have an uncomplicated public image, and are happy to demonstrate their mutual love. Perhaps it’s also a little bit easier to be a royal in Denmark compared to other countries? “I can’t answer that because I don’t know what it would be like to be a royal in another country,” the Crown Princess replies.

“We do protect them a little bit,” says Thorning-Schmidt of the public’s relationship with the royal family. “If they make the odd mistake, we make allowances. And that’s fair enough. A monarchy should be surrounded by a sense of ceremony and formality, and in Denmark we’re all quite good at preserving that.”

The Crown Princess paints a pleasant image of her day-to-day life in Copenhagen: “The Danes are proud of the fact that their royal family can go around freely in society. Because of that, there is a natural respect of your space. If I go into Copenhagen, or out to eat, or to the cinema with my children, I feel like we are given the space to do so.” She became a princess at the dawn of camera phones and social media scrutiny. “The positive side is that it means we can communicate more directly. On the negative side, everyone, everywhere, anytime can take a photo or a video. But what can you do? I make eye contact with people and smile. If you go for a walk and your dog wants to talk to another dog,” she says, referring to the family’s border collie, Grace, “well, you talk to the person who’s got the other dog.”

How to live with social media is an area at the forefront of the royal conscience. “It is now both a tool and a problem,” she says. “Social media can reinforce problems like bullying and loneliness, but we can’t always see it as the problem because it gives some unique channels to be able to reach out.”

Through the Mary Foundation, the platform and research institute she established in 2007, the Crown Princess deals with societal issues like isolation, harassment and domestic violence. “Since I can remember, I’ve found it difficult seeing what I interpret as people being alone, looking in, not understanding why they can’t be a part of something bigger than themselves. I’ve always had a curiosity to truly understand a situation and its consequences. That’s my drive for doing what I do, and the platform from where I lead.”

One day, her son Prince Christian will become Crown Prince and eventually King of Denmark. The royal family has announced they don’t expect “apanage” – the Danish equivalent of Civil List privileges – for their three younger children. Reflecting on the next generation, the Crown Princess says her concerns are related to the times in which we live. “You know, we have two teenagers in the house and teenage years are very transformative and vulnerable. It’s the years when you make mistakes, and mistakes are important. Hopefully you learn from them and get on the right path. So I hope that they continue to be given the freedom and space to make those mistakes and to come through those explorative years.”

From the window of her study, a trampoline is vaguely visible in the palace garden. A family photo graces a chiffonier. “We hope that they grow up to be strong and independent individuals, who will have the courage to follow their aspirations,” she says of her ambitions for her children. “It’s important that they know who they are, are proud of who they are and the family they belong to, and what that family represents to the Danes.”

Is that the secret to contemporary royal life? “I don’t think there’s a secret,” Crown Princess Mary says. “It’s being in touch and being close to the people: knowing what’s happening in society; which way are we heading; what are the new trends and challenges. It’s a natural, organic process that happens as generations come and go.” When it comes to creating a modern monarchy, it seems a Tasmanian candour can often speak a Danish truth.

Comments