Funds need clear standardised labels

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Natasha Ednan-Laperouse was 15 years old when she boarded a plane from London to Nice. After eating a shop-bought baguette that contained trace amounts of sesame — to which she was severely allergic — she collapsed during the flight and later died.

Following this tragedy, food retailers are now required to display a full list of ingredients and allergens on every item. This is Natasha’s Law.

The purpose of standardised food labelling is to create a simple and intelligible system that protects consumers from harm.

But when it comes to labelling financial products, the systems we have are so simple as to be nonsensical. Does the consumer gain anything from the ubiquitous generic warning that “the value of your investments can go down as well as up, so you could get back less than you invested”?

Investment funds carry a numerical rating ranging from 1 (low risk) to 7 (high risk) that tells us very little about the nature of risks involved. And while the consequences of mislabelling a fund are far from a matter of life and death, they can nonetheless be devastating.

This year I have spoken to many people who are stunned at the fall in the value of their retirement funds. They, and sometimes their financial advisers, fell into the trap of chasing returns, buying funds with the best recent performance.

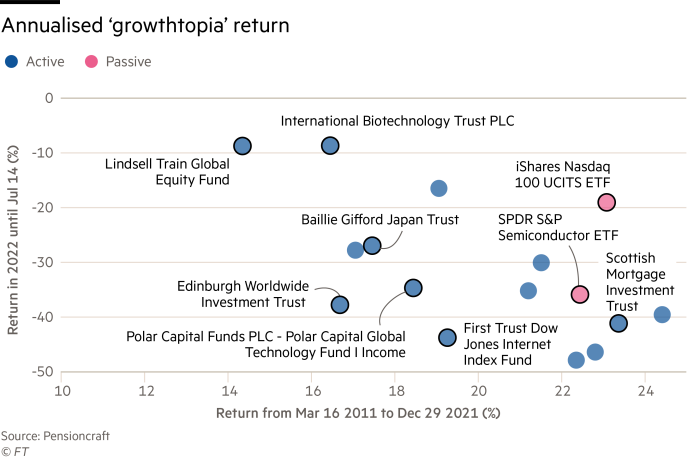

Over the past decade, these have been invested in growth stocks, predominantly in the US with its growth-friendly combination of huge technology-focused venture capital funds and near-zero borrowing costs. Let’s call that era Growthtopia. It was impossible to ignore annualised returns of 20 per cent for growth stocks from 2009 to 2021 and many investors were lured into the honey trap.

Since then, growth stocks have fallen sharply. The Russell 1000 Growth exchange-traded fund has fallen by almost 30 per cent and some of the most popular growth stocks, such as Coinbase, are down 80 per cent or more. But we all know, thanks to the Financial Conduct Authority, that the value of our stocks can go down as well as up, so what’s the problem?

The problem for most retail investors is understanding what they are buying. Some bought active funds in the hope that their outperformance was due to expert stockpicking. Instead, many active funds outperformed simply because of their tilt towards growth stocks.

The chart shows a selection of the largest, best-performing funds over the decade from 2011-21 which had a heavy tilt towards growth and which have, in some cases, almost halved in value this year.

So how can retail investors get a better sense of what they are buying in the funds market? I suggest a standardised approach to labelling a fund in three parts: a clear description of its investment style, a sensible benchmark and simple return attribution. Let’s see how that would work in practice, using a popular fund whose name doesn’t give much away: Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust.

Scottish Mortgage’s benchmark is the FTSE All-World Index, ostensibly because it invests in global stocks. However, this is not a good comparison, as it ignores one of the primary sources of Scottish Mortgage’s high returns and its dramatic fall this year — its tilt toward growth stocks.

A more appropriate index would be the ACWI Growth index from index provider MSCI which, like Scottish Mortgage, includes emerging market stocks alongside those from developed markets. This index invariably tracks the performance of the fund more closely.

If Scottish Mortgage is outperforming the global market while growth as a style isn’t, that is a great accomplishment. But outperformance when growth is outperforming isn’t nearly as impressive, as investors could buy the same style through a passive fund more cheaply. Choosing the right benchmark is key to determining this.

Finally, funds usually publish their returns over different periods alongside the performance of their benchmark. But we seldom know the source of return. Is it down to the fact that all equity markets are rallying? Is it driven by the style tilt of the fund? Is it due to currency effects, such as weakening sterling? Or is it due to skilful stock selection?

These are precisely the questions a model for attributing the sources of return seeks to answer by deconstructing a fund’s return into these different sources. A standardised approach to return attribution would shine a light on why a fund has outperformed or underperformed and help investors gauge whether any outperformance will continue.

The key question for most investors is how much of the return is down to the skill of the fund manager. That is, after all, why we pay more for active funds.

Active managers are unlikely to implement a standard labelling system themselves, just as food manufacturers had to be jolted into action with Natasha’s Law. It is down to regulators such as the FCA to ensure that investors have an objective insight into a fund’s ingredients. Only then can they gauge whether a fund is earning its fees.

Ramin Nakisa is a co-founder of Pensioncraft

Comments