Smart beta ‘value’ investing is ripe for a comeback

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Interested in ETFs?

Visit our ETF Hub for investor news and education, market updates and analysis and easy-to-use tools to help you select the right ETFs.

Bargain-seeking investors who focus on value stocks have endured a difficult time since the 2007-08 global financial crisis, as their strategy of buying unloved gems has failed to deliver the anticipated results.

Pioneered in the 1930s by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, value investing uses indicators such as dividend yields and a low price-to-book, or price-to-earnings, or price-to-sales ratio, to identify companies where the business potential is not reflected in the share price. It is an approach that has many professional followers, including Warren Buffett, the founder of Berkshire Hathaway.

Value stocks, historically, have tended to congregate in the energy, financials, telecoms, utilities and real estate sectors. But Andrew Lapthorne, a quantitative strategist at Société Générale, prefers to describe value stocks as an “assembly of problems” that some investors choose to avoid. “Value investors are buying whatever the problem happens to be — UK companies that were hit by Brexit, oil stocks after the collapse in crude prices, airlines during the pandemic,” he says.

Even so, the majority of US fund managers who try to pick winners from value stocks have failed to beat a passive value-stock benchmark over the past decade. Data from S&P Global show that, after their fees were taken into account, 86 per cent of large cap US mutual funds failed to beat the S&P 500 value index over the decade ending December 2020.

Managers of US small cap value funds did worse, with 97 per cent, net of fees, underperforming the S&P small cap 600 value index, over the same period.

Investors’ disappointment with the poor performance of active managers who try to pick winning stocks has fuelled a shift into low-cost exchange traded funds that track a broad index. Investors can now choose from 165 value ETFs, which have combined assets of $392bn, according to ETFGI, a data provider.

“ETFs offer a wide variety of readily assembled value strategies that can be used as building blocks within an investor’s overall portfolio,” says Deborah Fuhr, founder of ETFGI.

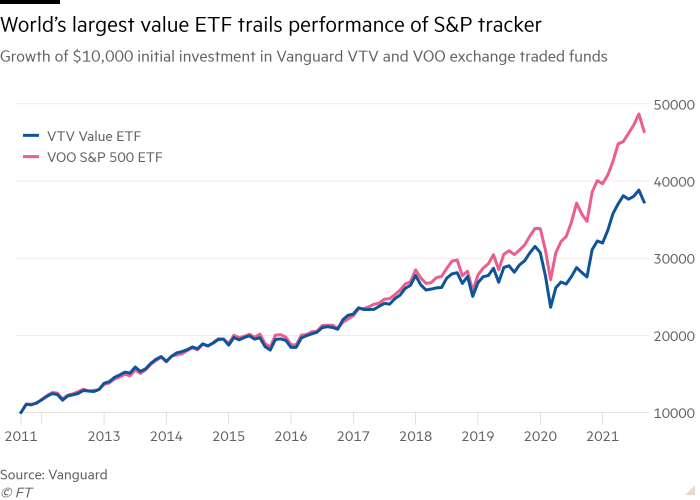

However, the strong growth of Big Tech companies — which has driven Wall Street’s record breaking rally has meant that value index-tracking ETFs have also struggled to keep pace with passive funds tracking the broader US market.

A $10,000 investment in the Vanguard fund known as VTV, the world’s largest value ETF, would have grown to $37,281 over the 10 years ending September 30. But a $10,000 investment in the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF, known as VOO, would have swelled to $46,426 over the same period.

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic last year triggered a further downturn for value stocks in both the US and Europe, as more investors shifted into tech stocks that benefited from homeworking during lockdowns and defensive shares in providers of consumer staples, for example.

But news of the development of successful vaccines against coronavirus triggered a rebound in value stocks from September 2020. Since then, the emergence of the more contagious Delta variant of Covid-19, along with fears about more lockdowns, has blunted the value-stock rally, but some managers say this marks only a pause.

“The economic and financial environment is shifting in favour of value stocks,” says Marco Pirondini, head of US equities at Amundi, the Paris-based asset manager.

He notes that US value stocks, as measured by the Russell 1000 value index, have recently traded at the biggest valuation discount to US growth stocks since 1999. The price to forward earnings for Russell 1000 value stocks stood at 16.8 times on September 30, compared with a multiple of 30.6 times for the Russell 1000 growth index.

Amundi expects this valuation gap to close as value stocks, historically, have outperformed the wider market when commodity prices are increasing, inflation is rising and interest rates are moving higher.

In the US, crude oil prices have jumped by two-thirds this year, while headline US consumer price inflation reached 5.4 per cent in September. “Rising commodity prices and higher inflation should support value stocks as we progress out of the pandemic,” says Pirondini.

Rob Arnott, founder and chair of Research Affiliates, one of the leading designers of smart beta investment strategies, says that value stocks remain priced at historically extreme valuation lows across most regions — the US, Europe, UK, Japan and emerging markets — apart from Australia.

He expects the rollout of vaccines to lead to an acceleration in global economic growth with the recovery providing a boost for cyclical sectors and value stocks.

“The opportunity to buy value stocks may be shortlived and we may wait decades for an opportunity of a similar scale,” Arnott says.

Click here to visit the ETF Hub

Comments