Culture war: How Danone kept making yoghurt in the pandemic

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Cyril Blanc was starting to go stir crazy.

Before the coronavirus struck, the 47-year-old salesman used to visit convenience stores and bakeries around Grenoble, promoting products from Danone, such as Evian water and Activia yoghurt.

Under the coronavirus lockdown, he had been forced to rely on phone calls and emails.

Desperate to break out of confinement, Mr Blanc volunteered to work at a nearby Danone warehouse which had been struggling to keep up with demand as consumers stockpiled food.

He swapped his usual business attire for boots, a safety jacket and insulated gloves and spent eight-hour shifts putting promotional stickers on yoghurts.

A warehouse boss watched closely to make sure he “could handle the pace”, said Mr Blanc. “We managed!” he chuckled. “The situation means that we are all doing things we’re not used to doing.”

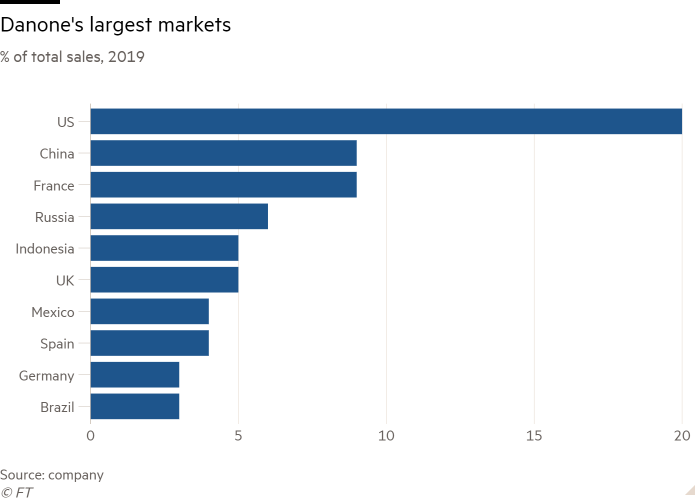

Based on interviews with executives and workers, this is the story of how Danone managed the challenges of Covid-19 when it hit its home in France. It has 8,500 workers here across 13 factories, eight logistics hubs and five offices, with ties to the countryside where it picks up milk from 2,000 farmers every few days.

Since the virus first hit Danone’s Chinese operation in January, the food manufacturer has adapted factories to social distancing, stockpiled masks, and expanded remote working. A central crisis committee has piloted the response, applying lessons from China to new countries as the virus spread.

Not only do strained supply chains, changing consumer demands, and increased production need to be managed, so does a global staff of 105,000 stressed-out human beings dealing with their own emotions. While some are overworked, others have felt listless as work has dwindled.

To get through the crisis, chief executive Emmanuel Faber told his executive committee to narrow their focus. “We will operate in a radically abnormal and often degraded situation for the duration of the lockdowns,” he said. “Forget the three-year plan. It doesn’t exist any more. Just get through the next 10 days, then the next month, and so on.”

Danone’s roots stretch back to the 1920s when its Spanish founder popularised yoghurt among the French as a healthy snack sold in small ceramic jars. Its bottled water, baby food and dairy brands are now mainstays on supermarket shelves. It was famously an acquisition target for Pepsi in 2005, until the French government declared Danone a national strategic asset. Today its €25bn of annual sales place it slightly ahead of Kraft Heinz and Mondelez.

But in business circles, Danone is also known for something else: it has espoused “responsible capitalism” since 1968 when its then-CEO laid out a dual commitment to business and social progress.

Mr Faber, a vegetarian, environmentalist and avid mountain climber, is still wedded to that ethos.

He announced in a video message in mid-March that Danone would guarantee all employment contracts and wages until June 30. Healthcare and childcare programmes would be extended, and a €300m fund would be put in place to help fragile suppliers. Employees in factories and warehouses in France would also receive a €1,000 bonus.

“There is no way we can continue to supply our customers and consumers with food if our staff does not feel absolutely safe at work and secure about their jobs,” he said.

The day after the announcement and 10 days into France’s lockdown, Mr Faber set out by car at 7am from his Paris apartment. Over the next 14 hours and roughly 600km, he checked on how employees and operations were holding up.

“It is important to me that there are not two companies — one working from home and one at work,” he said. “I wanted to show that Danone is united.”

His first stop was a logistics platform in northern France. It had been under great strain since lockdown. As supermarkets scrambled to keep shelves stocked, they changed orders frequently and asked that deliveries be made hours earlier than usual.

The warehouse was also feeling the effects of the spike in online ordering of groceries, which was altering the mix of what supermarkets were ordering. To cope, overtime shifts were added and temporary workers brought in.

Mr Faber then visited a factory near the Belgian border that made baby food and formula for the Bledina brand. It had ramped up production before the lockdown in anticipation of stockpiling — a key lesson learnt from China. Bledina sales in France jumped 70 per cent in the first week of the quarantine as parents snapped up child-friendly products such as fruit cups and apple sauce.

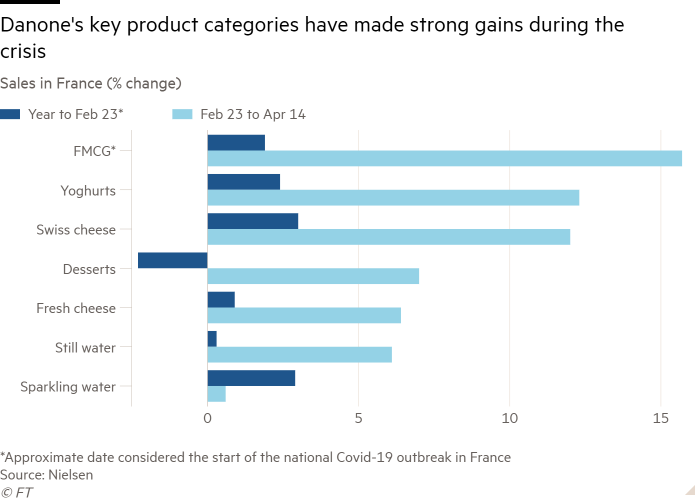

Production was having to be retooled at many of Danone’s factories to address changing consumer demand. People were opting for bigger packaging formats as they hunkered down at home. Danone increased production of yoghurts in packs of 16 and reduced the number of 4-packs.

The closure of cafés, bars, and cafeterias meant that sales of higher-margin, small bottles of water fell off a cliff. Suddenly 8-litre containers of Evian and Volvic were all the rage, and Danone was donating unsold 30ml bottles to companies making hand sanitiser to fight Covid-19.

“All our systems used to be lean and mean and super-optimised for efficiency,” explained Mr Faber. “Suddenly all that gets blown up and we suddenly have to cope with twice the volume than before in some products and half in others.”

Work at the factories had also been altered by social-distancing measures. Staff at each site were split into separate teams, shift times altered so they never met. Canteens and changing rooms for staff were reorganised to keep at least 2m between each person. Production lines that were too close together to make this feasible were shut down.

No outsiders were allowed in, complicating matters for the truckers who usually pick up or drop off merchandise and supplies. At some sites, Danone set up temporary bungalows for the truckers in the parking lots so they could shower and have a coffee without coming into the factory.

Initially, there were those who argued that the company was going overboard with precautions. At a meeting before the quarantine, some employees mocked the way the table had been set up to leave one chair empty between each person.

“People have a hard time understanding the level of contagion and how much the virus can spread,” said Bertrand Austruy, Danone’s human resources head, who leads the crisis committee. “They don’t believe it’s real at first, so you have to be authoritarian about applying social distancing.”

As France’s lockdown lengthened, stresses grew on Danone’s operations. Employees at a warehouse near Paris complained about not having enough protective masks.

Absenteeism crept up to reach 20 per cent at some sites, according to unions. Half of the team in charge of maintenance at one factory had to be quarantined after one person fell ill. A back-up team was dispatched from another site.

At Danone’s 130,000 sq m Evian bottling facility in the French Alps, freight trains that usually picked up finished products stopped operating, a knock-on effect of problems with the state national rail operator. Danone had to scramble to hire trucks instead, which carried less and cost more.

Denis Magnin, a security and facilities manager at the plant, fielded frequent calls from worried staff members from his new perch in his son's bedroom and wished he could reassure them in person. “I have only one desire — to go back to the plant! Everything has changed by working from home. It’s terrible but necessary.”

In return for the employment assurances and bonus announced by Mr Faber, management wanted the ability to reassign people, require overtime, and force people who did not have enough work to take vacation days during the lockdown.

Unions pushed back. Eventually they convinced Danone to set up online training programmes for employees with little else to do, so fewer of their vacation days would be confiscated. English classes, diversity training and workshops on mindfulness and sleep hygiene would be offered.

Nevertheless, only two of the company’s four unions signed the accord with Danone. The holdouts had wanted Danone to promise to trim the dividend. If employees had to make sacrifices, then so should shareholders, they said.

Mr Faber declined to comment on what he called “discussions within the family”.

For all the adaptation of the last few weeks, the hundreds of subtle changes, there is no end in sight. With countries still under lockdown, Danone last week postponed the decision on paying a dividend and scrapped profit forecasts. It has raised €800m in a bond issue to push out maturity on its €12.8bn of net debt.

Although it said last week that it had benefited from a first-quarter boost in sales due to “pantry loading” in Europe and North America, Danone made a stark admission that it was now “unable to predict” how Covid-19 would affect its ability to supply products and the demand for them.

As he navigated the uncertainty from his home office, Mr Faber took inspiration from his hobby of mountaineering. “My climbing gear and ropes are less than two metres away from my desk,” he said. “On a difficult and foggy route . . . never lose the orientation to the summit, and pay attention to your buddy’s energy level.”

Additional reporting by Domitille Alain.

This is the second article in a series looking inside companies that are grappling with the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. We earlier looked at John Smedley, the clothes maker that runs the oldest continuously operated factory in England

Comments