The challenge of unlocking the UK’s low productivity

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 2015, the Tory chancellor George Osborne argued that harsh welfare cuts were needed to support the UK’s transition away from “subsidised low pay” and low productivity. Six years on, Boris Johnson is using the same argument to justify his post-Brexit clampdown on low-skilled immigration.

The chaos in UK supply chains, he told the Conservative party conference this week, was “mainly a function of growth and economic revival”. But it was also part of a long overdue change of direction from a “broken model” of low wages, low growth, inadequate skills and low productivity — enabled by a ready supply of cheap overseas labour.

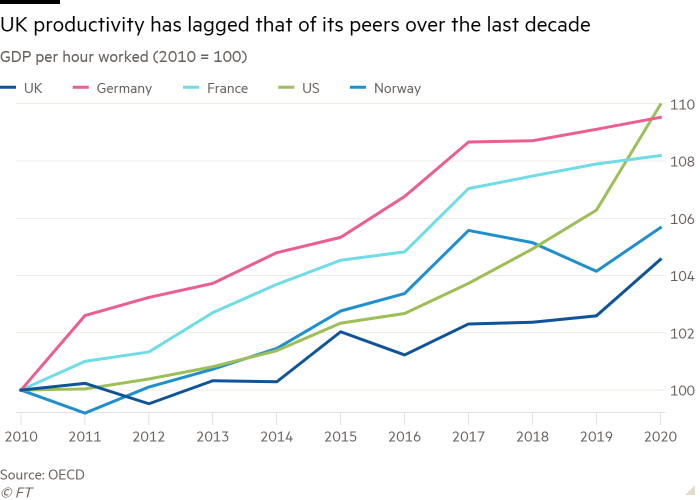

Economists are less convinced. Lifting the UK’s chronically poor productivity — the key to long-term gains in living standards — has been the goal of successive governments but it has proved elusive. In the decade leading up to the pandemic, output per hour worked grew at less than half the rate it had averaged in the years leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis. By the end of 2019, it was 20 per cent below the level it would have reached if it had continued on its pre-crisis path.

But such poor performance, witnessed in many developed economies but especially acute in the UK, had little to do with openness to EU workers. Instead, economists attribute it to international factors, such as stalling globalisation, and to UK specific ones, such as the rise in self-employment and the so-called “long tail” of poorly managed small businesses.

Huw Pill, the Bank of England’s new chief economist, said in written testimony to the House of Commons Treasury select committee this week that the UK had also “experienced three major waves of uncertainty”, in the form of the global financial crisis, the EU referendum and the pandemic, which would have made companies cautious about investment, innovation, and research and development.

“Migration is such a small part of this,” said Alan Manning, a professor at the London School of Economics who previously chaired the government’s migration advisory committee. The committee’s research showed that neither a very restrictive nor a very liberal approach on immigration would have any big effect on UK per capita gross domestic product, he said, adding: “I don’t think this boosterism is going to transform anything”.

Instead, the Brexit-induced truck driver shortage that has snarled up supply chains — with a clear hit to productivity in almost every corner of the economy — is simply the most acute example of much broader pressures becoming apparent across the UK labour market.

A monthly survey by advisory firm KPMG and the Recruitment & Employment Confederation published on Friday showed that recruiters were reporting the most intense pressures on pay for 24 years in September, in white-collar jobs as well as in the low-paid areas where shortages have been most visible.

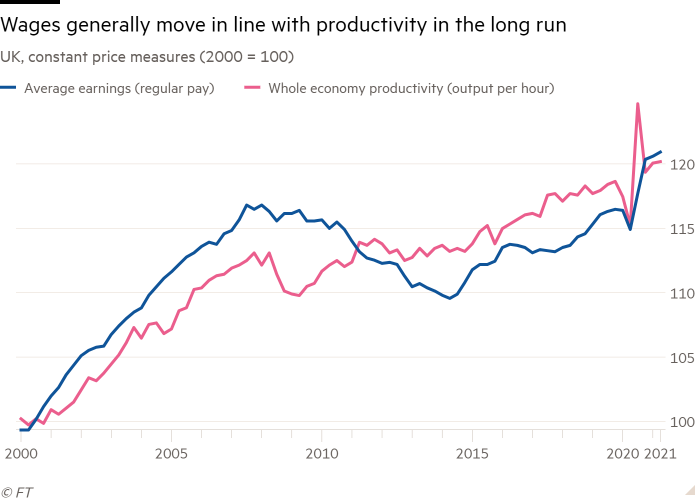

Business leaders argue these wage rises will simply feed inflation unless they are driven by higher productivity. “Ambition on wages without action on investment and productivity is ultimately just a pathway for higher prices,” Tony Danker, the CBI director-general, said on Wednesday.

But some argue higher wages could instead drive productivity gains — whether by prompting employers to invest more in labour-saving machinery or training, or by killing off weaker companies in the “long tail” that were unable to match the wages paid by more productive rivals.

Johnson suggested that in the absence of low-wage migration, businesses would be forced to confront their “failure to invest in people, in skills and in the equipment, the facilities, the machinery they need to do their jobs”.

However, this argument works better in theory than in practice, according to Jonathan Portes, a professor at King’s College, London. The UK’s experience of the minimum wage showed that higher pay did not necessarily hurt jobs, but nor did it lead to “dramatically higher productivity”, he said.

Kitty Ussher, chief economist at the Institute for Directors lobby group, also said there were “massive caveats” to the prime minister’s argument. First, wage rises would bite immediately, while productivity gains would take time. Second, there were sectors such as social care, where employers might find it “financially advantageous to have fewer people”, but productivity lay in the quality and time of interaction. There would also be individuals, especially those mid-career, who were keen to retrain for a better skilled, higher paid role — but did not necessarily have the time or means to do so.

Yet the shock of the pandemic could still give a much-needed jolt to UK productivity — for reasons that have nothing to do with labour shortages. Pill told the Treasury committee that on a “positive perspective”, many companies that had shut down completely now had “a chance to re-optimise and improve their processes as they restarted”.

A burst of new business creation could bring innovations that proved more productive, he added, and existing companies had automated or brought in technologies to support homeworking that could raise productivity in the longer term.

The government is also pressing ahead with investments in skills and infrastructure that have long been seen as the standard prescription for boosting productivity: Johnson promised this week to “solve the national productivity puzzle, by fixing the broken housing market, by plugging in the gigabit, by putting in decent safe bus routes . . . and by investing in skills, skills skills”.

But business groups say it is not yet clear whether action in these areas will match the rhetoric — and that ministers’ confrontational approach is not helping.

Neil Carberry, the REC’s chair, said it was “essential that government works in partnership with business to deliver sustainable growth and rising wages, rather than a crisis-driven sugar rush.”

“I don’t like the undertone of ‘if it’s not hurting it’s not working’,” said Ussher, who wants the government to give individuals more help to retrain, and businesses more support through the tax system to invest in skills — “so we don’t need to stoically go through pain but can adjust”.

Comments