Julie Curtiss’s art of the beautiful grotesque

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The 38-year-old French-Vietnamese artist Julie Curtiss has been causing much excitement in the art world with her twisted, caustic representations of life’s familiar visuals. Her rise has been rapid. In 2015, she was “a nobody”, as she puts it. Three years later, New York dealer Anton Kern began showing her work. In 2019, a small painting of a woman’s head with Princess Leia-style buns sold for $106,250 on the secondary market at Phillips New York, over an estimate of $6,000 to $8,000. It was followed by the sale that marks her record; a hammer price of $423,000 (around three times the estimate) for Pas de Trois, a canvas showing three hairy forms. Last year, Curtiss signed with White Cube: her first solo show in London opened earlier this month in its St James’s space.

When we speak in early spring, Curtiss is alone in her New York apartment, save for her cat Houdini, trying to focus on painting, bored with restrictions. “I want to live,” she says. “You need to experience life to paint about life.” She misses, like everyone, “the unexpected”, which is exactly what her work is all about: the odd, the perverse, the incongruous. Curtiss clashes the banal artefacts of pop culture and contemporary life with flickers of the grotesque. Things are not right, not where they should be.

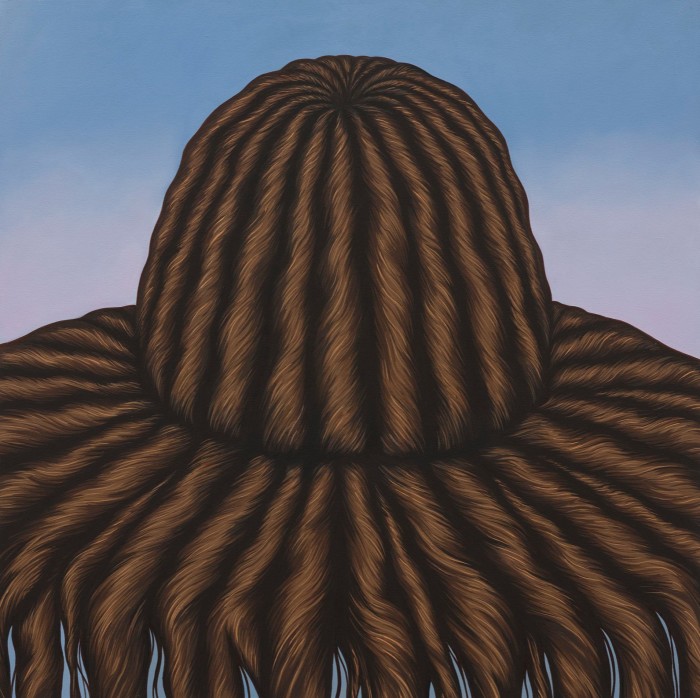

The canvases at White Cube, titled Monads and Dyads, showcase the motifs that have become Curtiss’s signatures: doubles and doppelgangers abound; there is a tension between order and disorder; the neat tiles of abattoir walls emphasise the curvaceous joints of hanging carcasses, and there is hair everywhere. Animals are covered in it – dark sweeps and licks and curls run across the hanging bodies of ducks or pigs. From above we see the shaggy scalps of nude figures, standing on hexagon tiles.

Hair is a great tool for perturbing; artists have used it to suggest beauty, other times to provoke, such as with Méret Oppenheim’s fur teacup from 1936, arguably the greatest surrealist sculpture ever made. In Curtiss’s work, hair appears both where one would expect – lush locks coiffed and lapping at collars – and where one wouldn’t, morphing into something shocking, repulsive, a symbol of death, perversion, chaos. Hair is among the props of femininity that she uses to create “female characters that are mysterious, but then also menacing in a certain way.”

Curtiss’s work is often cited in relation to the surrealists (indeed, her first inclusion at a White Cube show was 2017’s Dreamers Awake, about surrealism and featuring female artists). And yet, while Monads and Dyads certainly has a surrealist bent – visitors will see sculptures of sushi rice topped with lips, a straw hat filled with spaghetti – Curtiss, unlike Oppenheim with her teacup, does not seek to shock or surprise, but to “skewer”, as the show’s curator Susanna Greeves puts it.

“I have always been interested in the in-between. In the tension between opposites,” says Curtiss, describing an obsession with shadow selves, knock-on effects and double meanings. If surrealism is showing things out of place through juxtaposition, Curtiss’s work questions those boundaries, the very existence of “in place” at all. She feels that society’s promises of fulfilment and stability, the dreams used to keep things flowing and the rules of the game no longer hold. “Any gesture in one direction will have a repercussion in another direction,” she says. “Look at being married and trying to have a career. Or look at motherhood.” Her generation have watched as women have become more independent, but “in that process they have to give up on some things”, she says. “Even liberation has a price, freedom has a price.” She is interested in a kind of “passive aggression”, one that prioritises difficult questions, rather than a gut reaction.

As well as a surrealist, Curtiss is frequently dubbed a “millennial artist”. “The Millennial Art Star Julie Curtiss’s Paintings Now Sell for Half a Million Dollars. It’s Kind of Freaking Her Out” read a 2019 Artnet headline. While she can accept the surrealist tag, the latter feels lazy. “I hardly qualify as a millennial,” she says (Curtiss was born in 1982). And yet, she is pragmatic, conscious of the current art world vogue for young female representational painters. “There was a clear change after Trump happened,” she says. “New cycles were started, and I feel that I jumped at the right time because of the work that I was doing, being a female artist doing a certain kind of figurative work. Maybe also the fact people see me as a person of colour.”

The millennial tag is fed by the fact her work reproduces well on social media. She was, she says, “able to take advantage of the narrow Instagram moment when artists suddenly had a chance to promote their work independently of institutions or galleries and reach out to a new base of collectors”. Without social media – now too saturated for making a splash – she says she would have got “nowhere”.

Curtiss’s success, as well as the fact her canvasses recall past artists such as the Chicago Imagists, including Christina Ramberg who regularly painted hair, have led to some critical mutters. Of the latter, Curtiss is open to the debt she owes. “Before I had any kind of success, Ramberg was a strong influence on my work,” she says, adding: “It was a phase I had to go through. And I’m still working it out in the context of the work.”

Likewise, her CV, which includes time working in the studio of the commercially successful American artist KAWS (aka Brian Donnelly) who is known for cartoons and clown-like figurines, and whose current show at the Brooklyn Museum caused much pearl-clutching among critics, has led others to be dismissive simply by association. “The art culture is totally snobbish,” Curtiss says. “It’s two forces again. It’s the force of conservation, and the force of evolution… It’s a clash of the establishment, a clash of a new emerging base of collectors, who don’t have that elite art education and who have a different way to relate to art – but they now have the material means to push an artist when they really want to, and when they like it.”

And yet, according to Zoë Klemme at Christie’s, who presided over one of Curtiss’s secondary market sales, the buyers’ demographic is broader than you think. “You might be surprised – it’s not just the young crowd. Julie really does talk to a wide range of collectors, including very established clients.” For Curtiss, a priority is that: “I don’t want people to flip my work”, as was done by some early buyers who bought the works for a couple of thousand dollars. “You feel like you are losing control of it. And people become more interested in the retail value than what the work represents.”

Because she is young, and female, people presume that Curtiss’s work must be a pithy comment on feminism, consumerism, #MeToo, technology. But she is cautious of art as activism. Her canvases are not loaded with firm arguments, or single statements. “For me, art is not propaganda. I’m not sending a message,” she says. “I want to explore things. And when you explore things you don’t know where things are going to lead you.”

Though a committed “leftie”, Curtiss worries about the discourse of today, about whether there is space for such exploration. “There is so much focus on identity, what we are, and wanting to create a woman culture, a black culture, a white culture.” She tires of hearing about cultural appropriation. “That point of view, that white people are somehow the worst people on earth, it’s another side of narcissism,” she says. Identity is broad, she argues: “We are not one thing, not even two things, we are a sum of so many things.”

Visitors to White Cube will notice that Curtiss does not paint faces in her paintings. It’s another unsettling signature: figures’ heads are either turned away, or their features are absent, blank, the empty ovals sometimes grey, or ghoulish green, a void – who is this woman? What is she thinking? It can be read as a clapback to the very contemporary notion that all that any of us really want is to be “seen”. Shortly before the show’s opening, Curtiss reflected on the most visible parts of her identity and how they have helped make her a success: “I’m going to try and ride this wave for as long as I can.” Yet, in using her paintings to offer the right to be an enigma, Curtiss makes a case for the strength of being indecipherable, illusive, perhaps coy, perhaps undecided, perhaps biding one’s time.

Comments