Hong Kong’s Blindspot Gallery continues to break new ground

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Mimi Chun started a gallery in Hong Kong in 2010, she gave it a name that directly addressed what she was trying to tackle. She had studied photography and film, but found vanishingly few galleries in the city showing image-based work by local emerging artists. “There was a blind spot, and I wanted to fill in that gap,” Chun says.

Her Blindspot Gallery quickly become a hothouse for those artists, operating out of a 7,000-square-foot warehouse space in Wong Chuk Hang and a small venue in Central (which later closed). In the beginning, “the concept was really loose and vague,” Chun says, but Blindspot has come to encompass venturesome art of all kinds, by a multigenerational cast of artists from Hong Kong, mainland China and abroad.

Those figures have been winning acclaim. Sin Wai Kin, a Toronto-born, London-based creator of delirious work drawing on drag performance, Cantonese opera and a great deal more, was nominated for the Turner Prize last month. A little more than a week later, Angela Su, who makes intricate drawings and videos, unveiled a solo exhibition representing her native Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale.

Such accolades have brought new interest — and potential new buyers — to Blindspot. However, “if people suddenly become very keen, it always scares me, and I tend to push people away,” Chun says, speaking by video from a Hong Kong quarantine hotel, having toasted Su in Venice. “I like people to take it slowly and digest.”

That approach has earned support from critics and curators. “Blindspot always puts on a meticulous exhibition,” says Hera Chan, an adjunct curator of Greater China for Tate, who splits her time between the city and Amsterdam. She cites a 2019 show by Luke Ching Chin Wai and South Ho Siu Nam, whose solo works featured imagery of weather events and typhoon damage in the city, a poignant display of disorder amid protests that the government was trying to quell. Blindspot has become “a space of gathering, genuinely, in Hong Kong”, Chan says.

Su joined Blindspot’s roster more than five years ago, after a collector told her, “Oh, you should really see Mimi,” the artist recalls. At their meeting, “I could feel her passion and dedication to showing Hong Kong art,” Su says from Prague, part of a post-Biennale European tour. “It’s not all about making money. It’s really about nurturing artists.”

“You can feel that they trust you,” artist Trevor Yeung says of Blindspot’s staff, speaking by phone from a London residency. One sign of that trust: he regularly forgets the prices they set together for his art, he says. Another is the freewheeling nature of the work that he can stage there. Hong Kong-based Yeung, who was born in China’s Guangdong province, has just closed a show at the gallery with tender, melancholy photos of nature, as well as 100 pillows shoved into a crevice and plants suspended from the ceiling by straps.

Hong Kong is, of course, going through seismic changes, following the passage of the national security law in 2020. “You have to be very careful and responsible for what you’re saying,” says artist Leung Chi Wo, a veteran of the Hong Kong art scene, and a co-founder of the revered Para Site nonprofit space. Chun concurs. “We’re constantly contemplating what to do, trying to understand what the line is and tip-toe around it,” she says. “Which is a very interesting learning curve. I think lots of mainland Chinese artists have done that. It’s just our turn now.”

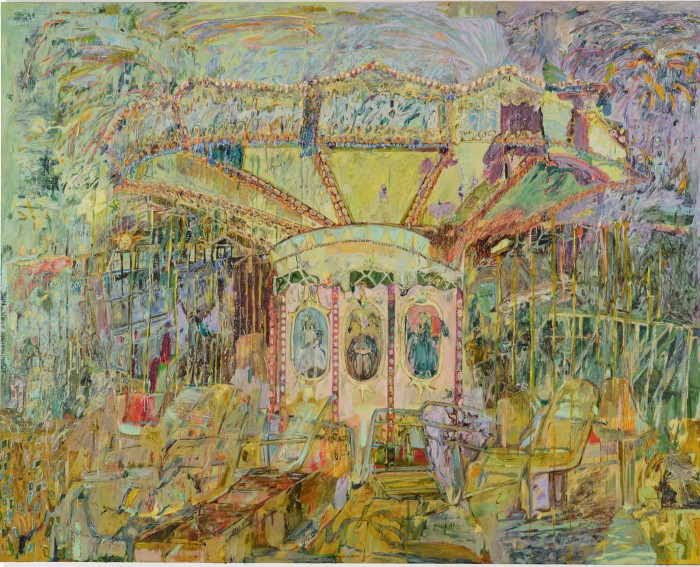

These shifts have shaped Blindspot’s business. Early in its run, many of Chun’s collectors were foreigners living in the city. Now, “all my expat friends are gone, so no more expats buying”, she says, explaining that, before departing, some stopped by to purchase works to remember their years there. At the same time, residents from mainland China who did not formerly visit have been coming during the pandemic, she says. The week of Art Basel Hong Kong, gallery visitors will find tough but alluring paintings — barely legible landscapes and figures amid virtuoso abstract passages — by the young local artist Un Cheng.

Meanwhile at the fair, which runs May 25-29, Blindspot will offer a selection of its artists. How would Chun describe her taste? “I like beautiful paintings and beautiful vintage photographic prints,” she says, “but what really makes me want to show art, and the kinds of artists I want to work with, are those who make work that intrigue me.” Twelve years in, a commitment to experimentation continues to define the gallery, as shown by an expansive video screening programme called Play and Loop that it has run the past three summers.

From the start, Chun has structured her operations to facilitate a measure of risk-taking. “I tried to have the smallest humanly possible cost,” she says. Her team of two (herself included) has grown to a modest six, and she has owned her space in industrial Wong Chuk Hang since the beginning, long before the area became an arts destination. “To run my current programme in the way I want to, without any compromise, it’s not possible if I had to pay the current rents, it’s just not possible,” she says. “Or I have to compromise, I have to show more beautiful paintings.” Catering to the market like that is not something you can imagine her doing.

Comments